Naturaleza muerta, 1931

This painting, done in the middle of her time in Paris, sets a theme for Peláez’s fascination with still life and fruit early on. The visible brush strokes mirror the ethereal painting style of Romañach, but the backgound is dark and obscure with pops of orange and red that speak more to the color influence that Peláz received from Exter. This still life compared with her others shows a development in her work through contrasting and developing styles and colors. During this time Peláez was still discovering herself as an artist, which is reflected in the style variety of her paintings.

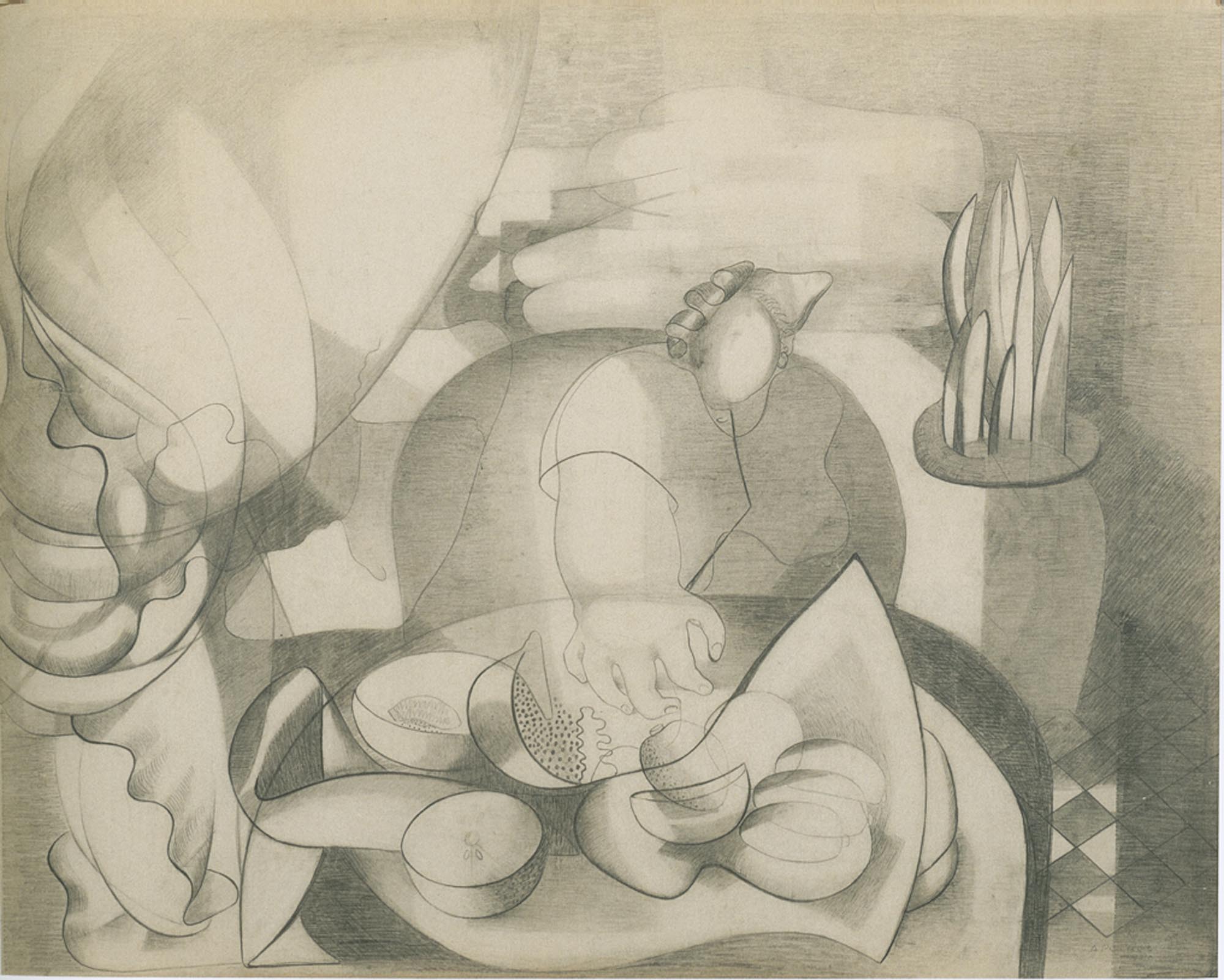

Naturaleza muerta con frutas, 1935

Peláez painted a large amount of still life scenes, and because of this her progression of style is the easiest to spot here. This still life bridges a wide gap between some of her earliest (Naturaleza muerta, 1931) and her latest (Naturaleza muerta con peces, 1958). Here Amelia is still using many of the muted colors that she practiced with in earlier works, but her signature style is starting to become apparent in the simple shapes she chooses to portray and how she shows them. Her brush strokes are much less visible here, and her fascination with fruit has continued. There is little influence of the Cuban culture and architecture in this painting, but colonial themes are shown in the simple table setting and decor.

Autoretrato, 1935

Amelia’s time experimenting with pencil is significant because it marks an apparent change in her use of color as an artist. Paintings before this time used darker shades and more somber tones, while after 1936 when she jumps back in to the world of color she does so much more vibrantly than she did before. Amelia produced few self portraits, and this is one of the first. Her love for strong lines is showcased well in pencil, and although this is a scene of her at a table with fruit there is a large curving abstract form on the left that expresses movement and complexity in its lines. The fruit on the table represents Amelia’s fascination with femininity and fertility, with seeds spilling from one fruit that is obviously ripe. The featureless woman that is Amelia seems to represent her disconnect from the world of her art. She loved to paint and create but seldom shared the meaning behind her pieces or discussed them.

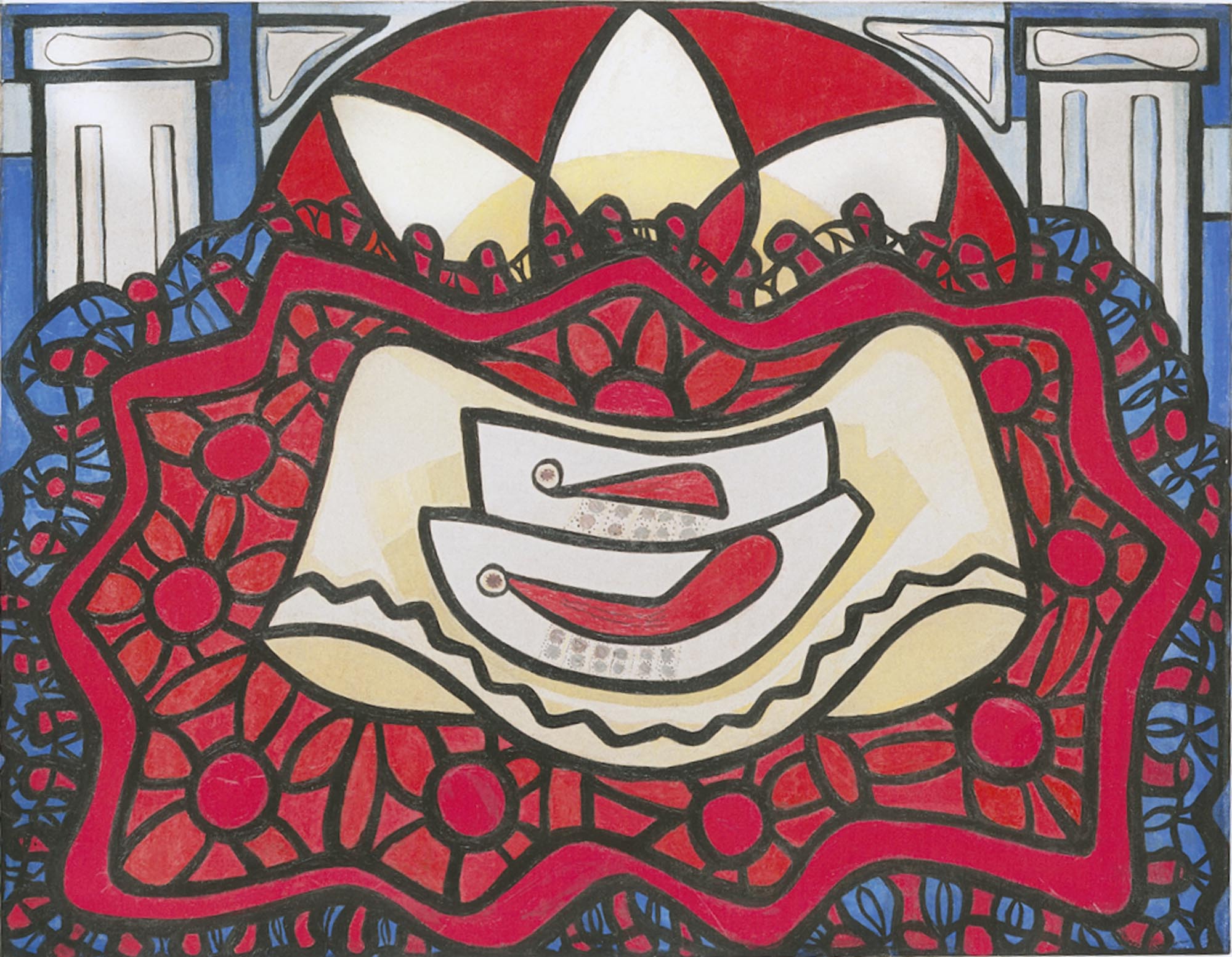

Papaya, 1940

Amelia’s fascination and stylistic representation of female fertility is profound in Papaya. Done in hues of red and yellow contrasted with black, the dramatic architectural influence that Peláez’s paintings eventually show is just beginning to enter her work and is very subtle here. On the bottom left and top center of the image there are thin black patterns that draw in baroque ironwork, but the focal point of the image is very clearly the fruit. The papaya, brightly colored and sitting on an even brighter table, is a shining symbol of fertility and female sexuality. Amelia was beginning to discover her role as a vanguardia painter in the late 30s and early 40s, and the way that she stayed true to herself while representing different aspects of her country was through addressing the role and individuality of the Cuban felame.

Autoretrato, 1946

A second self portrait, this one is unique because it is a painting in black and white. By this time in her career color was a staple in Amelia’s paintings, and a lack of color in this painting of herself is intriguing. The rest of her trademark styles are all present: thick black outlines; columnar representation of architecture; and an intricacy of decoration that suggests baroque ironwork. Some of the lack of color may be to represent the oppressed Cuban woman. Amelia’s fascination with color comes from her ability to explore and see the outside world, and her sphere of influence in the vanguardia used tradition to appeal to the culturally elite. She was trying to help connect colonial women with Cuban culture and give them the ability to see the beauty for themselves.

Mujer con pez, 1948

Mujer con pez is a piece that demonstrates Amelia’s fascination with and inclusion of baroque themes in her work. The focus of the piece is a woman holding a fish, possibly surrounded by two more. In the foreground and all around her is intricate black line detailing. She seems to sit in front of a house, which is also decorated intricately and surrounded with various complex patterns and lines. Although the baroque lines at first appear to be added on haphazardly, they are in fact woven in to the hair of the woman and in to all of the details of the house and the fish.

Naturaleza muerta con peces, 1958

This work brightly portrays everything that has come to represent Amelia as an artist. The background is framed by two solid standing white columns, the type of which line the porch of her house La Villa Carmela. In the background above the center table is an arching stained glass window, which draws influence from the stained glass that was prevalent in Cuban colonial architecture. The window is simple but brightly colored. Lastly, the table in the center is surrounded by patterns that mimic both stained glass and the wrought baroque ironwork that is represented by thick black lines in many of Peláez’s paintings.

Porrón de gallinita, 1953

Made during her time in a Santiago de las Vegas studio, Amelia’s pottery acts as a vessel for the paintings she puts on them. These two, called Porron de gallinita (which translates to chicken hen) show extremely cubist blue hens. Amelia didn’t paint many animals, however, she did have a fascination with birds. Amelia painted surrounded by birds in her backyard, and when she was deep in her pottery phase she moved across the street from her studio so as to be closer and ended up raising chickens there. The chickens on these pots are likely inspired by the ones she raised just across the street.

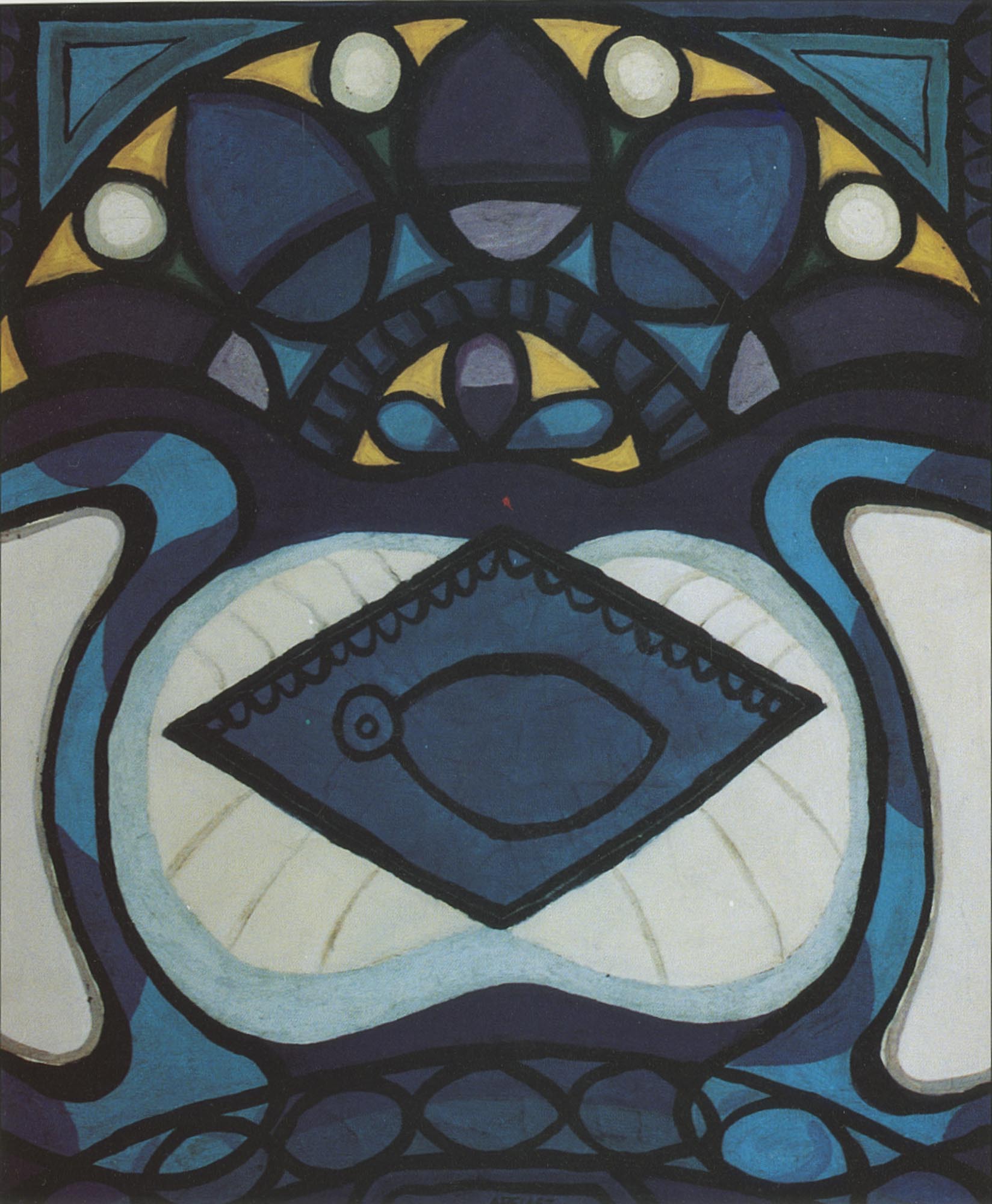

Sin título, 1964

1964 was the year that Amelia painted Sin título and also the year that her mother passed away. While Peláez usually used a vibrant pallet of many hues, the blue tone of this painting may be a way to portray grief. Amelia outlived her mother and many of her sisters, and the loss of companionship is a difficult event. An arc of stained glass can be seen in the background here, as well as baroque-invoking details on the bottom of the piece. The only color other than blue here appears in the stained glass window, and the yellow seems to represent the sun coming into the dark blue room from outside.