Amrita Sher-Gil was born to Umrao Singh Sher-Gil, a Sikh scholar, and Marie Antoinette Sher-Gil, an accomplished Hungarian musician, on January 30th, 1913. Her childhood was spent in Hungary, where she was exposed to the artistic and cultural hub of Budapest and her mother’s elite social circles. (Ananth 13) She grew up under the influence of her father’s intellectual and philosophical ideas and, following the tradition of her mother’s family, was also educated in music and cultural subjects. (Ananth 13) As a child, Sher-Gil was self-possessed, intelligent, and stubborn, refusing to adhere to formal drawing instruction. (Dalmia 15-17)

In 1921 the family returned to India, due to financial difficulties and growing unrest in Hungary, followed by a brief period in 1924 when Marie Antoinette and her daughters lived in Italy as Amrita’s mother pursued an Italian sculptor with whom she was having an affair. During her time in Florence, Amrita was expelled from Catholic school for drawing a nude figure, and developed interest in the Renaissance masters, which would later prove to be an influence in her painting. (Dalmia 19-20)

Back in Simla, India, Amrita spent time with her uncle Ervin, a painter and noted anthologist who was an important early influence on Sher-Gil’s artistic development. He provided her with early drawing lessons and encouragement as well as exposure to the wider Indian cultural world beyond her mother’s social circles; she later said to him, “It is to you I owe my skill in drawing.” (Dalmia 23-25) Baktay helped to convince Amrita’s parents to move to France in 1929 in order to further her artistic training. (Dalmia 25)

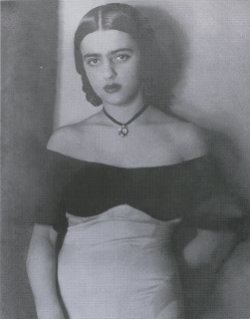

In Paris, Sher-Gil received more formal artistic training at the Écoles des Beaux Arts and was exposed to modernist artistic tradition and artists whose work would influence her paintings, such as Van Gogh, Cezanne, and Modigliani. (Mathur 519) Paris introduced Sher-Gil to the vibrancy of city life, which stimulated her creativity; she was an active participant in the city nightlife and Bohemian lifestyle. Her time in Paris was also the beginning of a series of brief love affairs with both men and women, following a disastrous engagement that ended with venereal disease and an abortion. (Dalmia 34-36) During her time in Paris, Sher-Gil painted portraits of personalities within the city as well as self-portraits; her works became gradually more sophisticated. She received some recognition for her works, despite struggles as an outsider in the art world, being a female and non-Western.

exposed to modernist artistic tradition and artists whose work would influence her paintings, such as Van Gogh, Cezanne, and Modigliani. (Mathur 519) Paris introduced Sher-Gil to the vibrancy of city life, which stimulated her creativity; she was an active participant in the city nightlife and Bohemian lifestyle. Her time in Paris was also the beginning of a series of brief love affairs with both men and women, following a disastrous engagement that ended with venereal disease and an abortion. (Dalmia 34-36) During her time in Paris, Sher-Gil painted portraits of personalities within the city as well as self-portraits; her works became gradually more sophisticated. She received some recognition for her works, despite struggles as an outsider in the art world, being a female and non-Western.

In 1934, Sher-Gil returned to India, feeling that her experience at the heart of Western modern art had only led her to a deeper appreciation for Indian art and to the realization that “a fresco from Ajanta or a small piece of sculpture in the Musee Guimet is worth more than a whole Renaissance.” (Ananth 14) She felt that the color, light, and natural  environment of India would improve her painting and helped her to develop her style more naturally. (Ananth 19) Sher-Gil enthusiastically embraced Indian culture, deciding to wear only saris and expressing a desire to paint India’s poor honestly rather than in a romanticized manner. (Dalmia 59-61) Sher-Gil was inspired by the paintings at Ajanta and the Cochin frescoes. During this time, her work began to blend Eastern and Western styles, combining Indian subjects and themes with modernist techniques. She also focused on simplifying her paintings, concentrating on form and color as much as subject. Although some criticized this departure from sentimentalism as a lack of feeling for the Indian people, Sher-Gil sought, through her work, “to be, through the medium of line, color, and design, an interpreter of the life of the people, particularly the life of the poor and the sad…on the more abstract plane of the purely pictorial.” (Tillotson 68)She became more well known in the Indian art world, although she was criticized for the Western influence her painting displayed and its departure from the Bengal School of painting, the predominantly accepted art style of the time, and her paintings still did not sell as well as she would have wanted. (Dalmia 104)

environment of India would improve her painting and helped her to develop her style more naturally. (Ananth 19) Sher-Gil enthusiastically embraced Indian culture, deciding to wear only saris and expressing a desire to paint India’s poor honestly rather than in a romanticized manner. (Dalmia 59-61) Sher-Gil was inspired by the paintings at Ajanta and the Cochin frescoes. During this time, her work began to blend Eastern and Western styles, combining Indian subjects and themes with modernist techniques. She also focused on simplifying her paintings, concentrating on form and color as much as subject. Although some criticized this departure from sentimentalism as a lack of feeling for the Indian people, Sher-Gil sought, through her work, “to be, through the medium of line, color, and design, an interpreter of the life of the people, particularly the life of the poor and the sad…on the more abstract plane of the purely pictorial.” (Tillotson 68)She became more well known in the Indian art world, although she was criticized for the Western influence her painting displayed and its departure from the Bengal School of painting, the predominantly accepted art style of the time, and her paintings still did not sell as well as she would have wanted. (Dalmia 104)

Sher-Gil married her cousin, Victor, with whom she had been close for some time. Her parents, especially her mother, disapproved of the marriage, because they were related and also possibly, in Marie Antoinette’s case, because Victor was neither wealthy nor a prominent social figure. (Dalmia 108) Her marriage caused considerable estrangement between Sher-Gil and her parents. It in no way, however, hindered her sexual exploits, as she continued to have affairs during her marriage, seemingly with Victor’s approval. (Dalmia 111)

Sher-Gil married her cousin, Victor, with whom she had been close for some time. Her parents, especially her mother, disapproved of the marriage, because they were related and also possibly, in Marie Antoinette’s case, because Victor was neither wealthy nor a prominent social figure. (Dalmia 108) Her marriage caused considerable estrangement between Sher-Gil and her parents. It in no way, however, hindered her sexual exploits, as she continued to have affairs during her marriage, seemingly with Victor’s approval. (Dalmia 111)

During her last years, she began to draw elements from Mughal miniature paintings, understanding more fully both the subjects of her paintings and the subtleties of form that were necessary to communicate the tension and expression Sher-Gil desired for her paintings. (Ananth 24) She began to experiment more often with three-dimensional forms and animal subjects, the latter probably inspired by her time in Bihar, known for its elephants and tigers. (Dalmia 138-139) She also focused more deeply on the subject of women as individuals and their situation within Indian society. (Ananth 24) In 1941, however, the confidence about her work that had arisen from these developments evaporated. Sher-Gil began to feel a sense of ennui in her work as well as in her marriage; soon, she became depressed and stopped painting, and died on December 5th, 1941. (Dalmia 141,173) The exact circumstances of her death are unclear; it is believed that she died of food poisoning, although there is suspicion that she died while having an abortion, and Sher-Gil’s mother believed for a time that her daughter had been poisoned by Victor. (Dalmia 179-181)