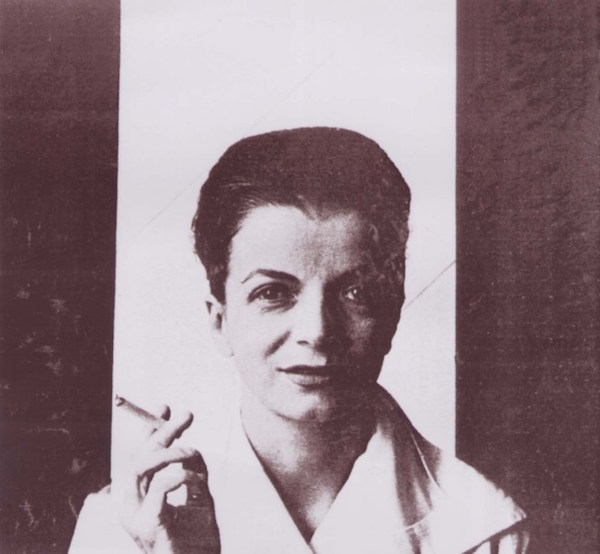

Lygia Clark was born October 23, 1920, in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. According to her writings, she had a difficult childhood; she mentions traumatic and abusive experiences and suggests that she may have stayed in a mental institution at some point during her childhood (Butler 235). She married Aluízio Clark Ribeiro in 1938 at the age of eighteen, and the pair had three children: Elizabeth (1941), Álvaro (1943), and Eduardo (1945). Clark seems to have had trouble with the idea of motherhood throughout her life. As she explains in a 1971 letter to Hélio Oiticica, a close companion and regarded as her artistic counterpart, she felt that “as a mother I have nothing left to give, even in relation to my children. I am tired of being the mother and the father also.” (Butler 20) cites her last pregnancy and subsequent “postpartum psychoses” as the beginning of her artistic career (Davis), and in 1947 she moved to Rio de Janeiro to pursue her art, studying with landscape artist Roberto Burle Marx (Carvalho).

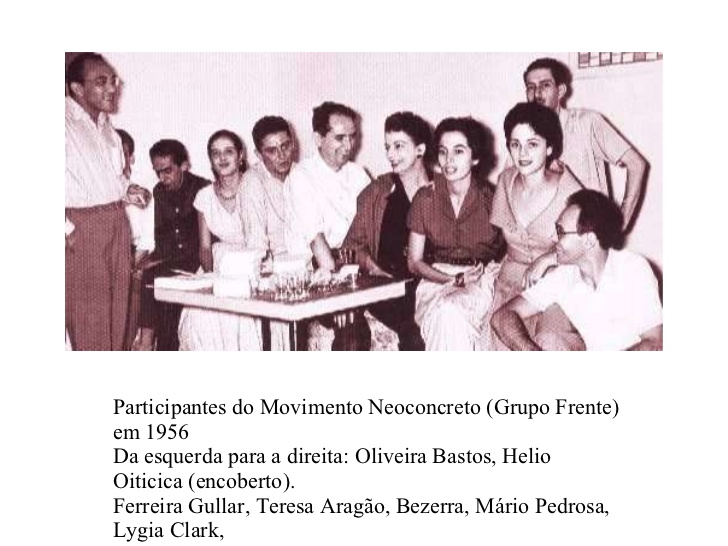

From 1950 to 1952, she lived in Paris with her children, studying under artists such as Fernand Léger and other painters. She and her husband divorced in 1953, and in 1954 she participated in the first exhibition of the artists’ group “Grupo Frente.” (Butler 311)

During this period, she worked mainly on paintings but was already beginning to question the notion of space in traditional painting, working hard to cultivate what she referred to as the “organic line” in such works as Modulated Space and Egg. She traveled to Rio de Janeiro and to Belo Horizonte frequently to work and to participate in exhibitions. During the 1960’s, her work transitioned from painting and sculpture to more subjective, interactive pieces, such as the Bichos group of movable sculptures and others such as Cocoon and Trepante, which often incorporated metal and wood structures. Her work sought to create art not as a static object but as an interactive experience between the spectator and the piece using “a mode that accounted for time and change through the experience of the viewer (Butler 20).

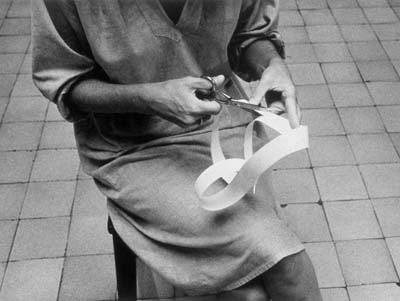

In 1963, she created her Caminhando work, which many consider to be her breakthrough in transitioning from the art object to what she called a “proposition” -the idea of action, prompted by the artist, as an art piece.

Though Clark was not directly politically involved -she often felt guilty and frustrated with the political complacency that her prosperity allowed (León 1)- her works often relate to the political turbulence and dictatorial repression of the political environment of Brazil in the later 20th century. She felt that the inequalities of the political and social world translated into the art world as well, and through incorporation of the spectator into her works she sought to combat her view that “modern art is not communicating and it is becoming more and more a problem of the elite” (Butler 24). In 1964, she began her Nostalgia of the Body series, which often included clothing or masks and attempted to evoke feeling in the participant through interaction with various “sensory objects” and other participants.

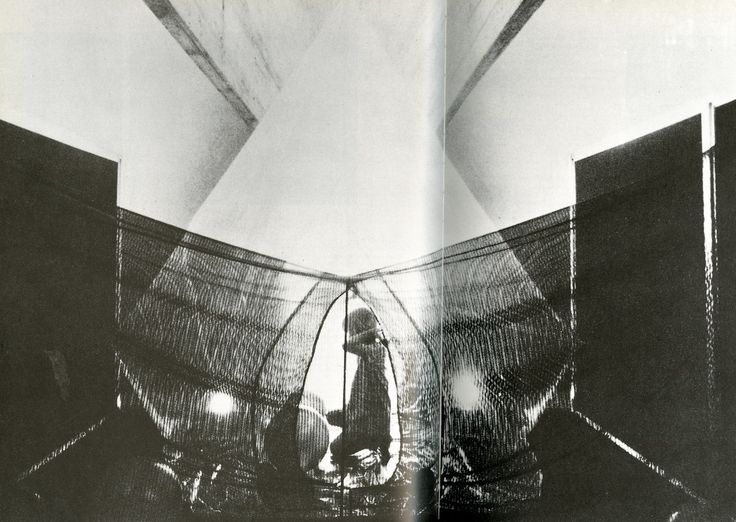

Her House of the Body work, created in 1968, was an artistic experience in which she replicated the process of conception and birth through sensory experiences in a series of rooms. This piece is one of many that draws from biological processes such as conception and birth as well as consumption and death; perhaps such pieces were her way of exploring her discomfort with her role as a mother.

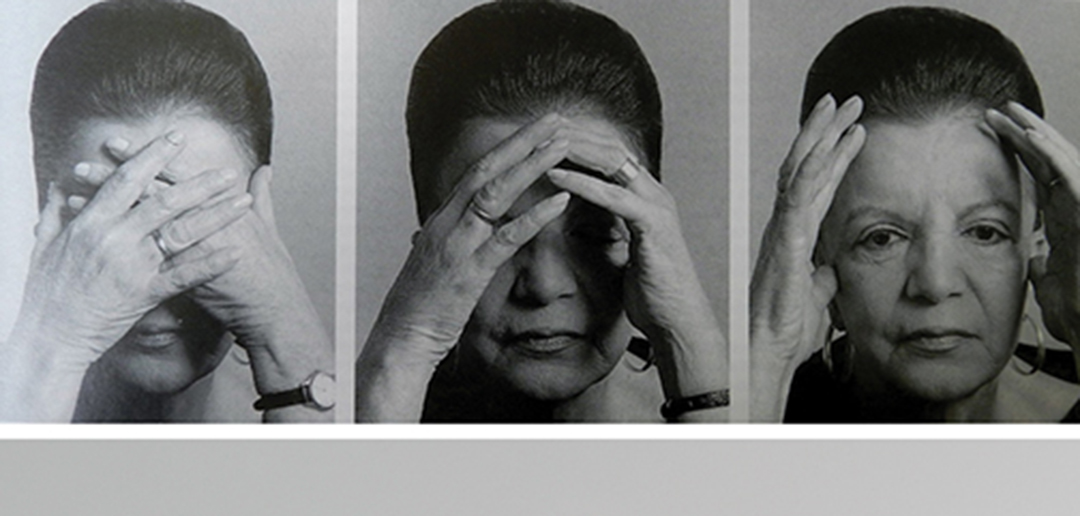

In 1968, she returned to Paris due to the political repression of these times and was offered a position teaching a course at the Sorbonne in 1972. Clark returned to Rio de Janeiro in 1976. She continued her work into the 1980’s focusing more narrowly on individual art therapy, which involved psychoanalytic ideas and sensory objects similar to those in her earlier works. Clark died April 26, 1986.