“Back in the day when folks were living in uninsulated homes–shacks, quilts were the method of keeping you warm at night, but in the spring and the summer, you’d put them up, put them in your chest of drawers” – Kim Kelly, volunteer Executive Consultant – Freedom Quilting Bee Legacy

A Brief History

Gee’s Bend, or Boykin, Alabama, is an area north of the Alabama River. In Gee’s Bend, most people are direct descendants of enslaved people from a cotton plantation established in 1816 by Joseph Gee. In 1845, following the accumulation of significant debt, the Gee family relinquished ownership of this land, in addition to 98 enslaved people, to Mark Pettway. This last name remains embedded in the lives of Gee’s Bend residents, as enslaved people were forced to assume the enslaver’s surname. Residents remained in the area until emancipation in 1863, though many people stayed in Gee’s Bend. This was due in part to the subjugation of many people to an exploitative tenant farming system, which kept farmers in a continuous state of debt.

Gee’s Bend remained a primarily farming community until 1962. When Congress built a dam and lock on the Alabama River at Miller’s Ferry, the 17,200-acre reservoir flooded much of the Gee’s Bend farming area, devastating their crops and ability to continue farming for food and revenue. This occurred in combination with growing participation in the Civil Rights Movement. In response, white officials discontinued the ferry service to Gee’s Bend across the Alabama River, effectively isolating the community, a service which was not restored until 2006.

In response, in 1966, more than 60 quilters worked together to create the Freedom Quilting Bee, a Black women’s cooperative working to inspire national interest in quilting and patchwork.

“Freedom Quilting Bee was born in March 1966 as an outgrowth of the civil rights movement as a beacon of hope, a battle for economic survival and a quest for dignity” – Freedom Quilting Bee Archive

These women developed contracts with Bloomingdale’s, Sears, and other national companies to develop anything from made-to-order quilts to small baby-sized quilts. These quilts, created from a tradition of piecing together fabric and clothing scraps, come from hundreds of years of intergenerational work—surviving slavery, Jim Crow, and continued oppression. The quilts became more well-known nationally and internationally following the 2002 exhibition The Quilts of Gee’s Bend.

“The Bee was the first business Black people in Wilcox owned. It was the first time I knew I was special, the first job I had” – Nettie Pettway Young

Public Response

While public response was positive, the 2002 exhibition The Quilts of Gee’s Bend heavily emphasized the authenticity of the Gee’s Bend artists at the expense of their story. While brief mentions of the subjugation of Gee’s Bend residents seemed obligatory across opinion pieces and reviews, many focused on comparisons between Gee’s Bend quilts and white contemporary painters. A 2002 review of the show from a Texas-based art publication states, “You are more likely to think comparatively in terms of Kenneth Noland, Ellsworth Kelly, or Ad Reinhardt than the historical traditions of American quilting.” Another review, this one from New York Times art critic Michael Kimmelman, notes that the quilts are some of the most “miraculous works of modern art America has produced. Imagine Matisse and Klee (if you think I’m wildly exaggerating, see the show), arising not from rarefied Europe, but from the caramel soil of the rural South.”

The reviews center comparisons between the quilts and primarily male, white contemporary artists, presumably in an attempt to wrap the quilts up within the art world. The same Texas blog writes, “But the 70 quilts by 45 artists that comprise The Quilts of Gee’s Bend were not made to be art, of course.” Critics at the time were impressed by the artistry of the quilts. However, for the work to be acknowledged as fine art, critics and the public relied on culturally powerful institutions, including the New York Times and the Whitney Museum.

However, in comparing Gee’s Bend quilts to completely unrelated works made by white painters, museums circumvent the inherently political basis that Gee’s Bend quilts are founded on and ignore the reparations necessary to begin to appreciate these quilts. In implying that the quilts were not actually art until the New York Times said so, Gee’s Bend is framed within a colonizing power that feels justified in providing an incomplete display of these quilts. This immediate response, and the underlying societal beliefs that prompted it, informs much of what this project works to investigate.

Where Are These Quilts Located Now?

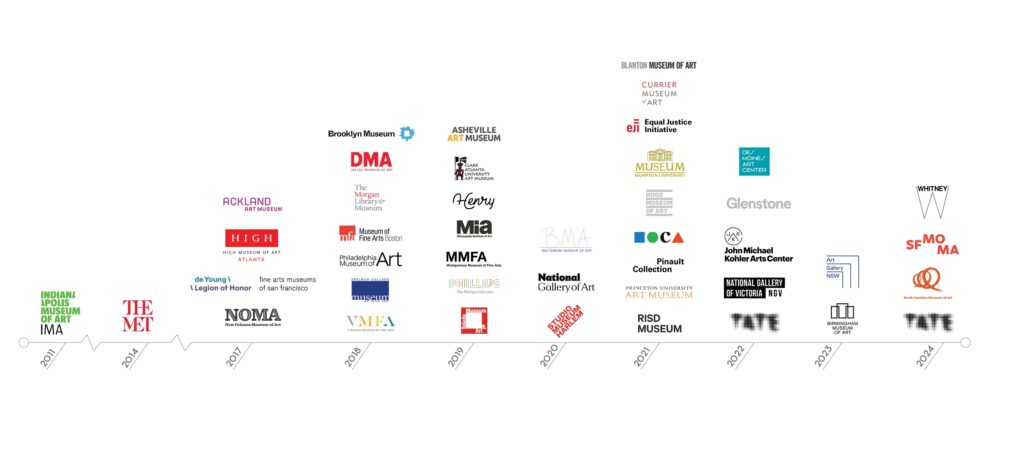

After the 2002 exhibition, Gee’s Bend quilts have spread across the country and world in expansive exhibitions.

Click on Any Image to Learn More about the Quilt Location or Artist

Arnett, William. 2006. “Gee’s Bend: The Architecture of the Quilt.” In Gee’s Bend: The Architecture of the Quilt. Edited by Paul Arnett, Joanne Cubbs, and Eugene W. Metcalf Jr. Atlanta: Tinwood Books.

Art Review; Jazzy Geometry, Cool Quilters – The New York Times, www.nytimes.com/2002/11/29/arts/art-review-jazzy-geometry-cool-quilters.html. Accessed 7 May 2025.

Dairen, Joshua. “From Slavery to National Fame: The Gee’s Bend Quilts That Changed Modern Art.” Al, 15 Dec. 2023, www.al.com/life/2023/12/from-slavery-to-national-fame-the-gees-bend-quilts-that-changed-modern-art.html.

Fishbach, Amy. “The Quilts of Gee’s Bend.” Glasstire, 2 Sept. 2002, glasstire.com/2002/09/02/the-quilts-of-gees-bend/.

“History of Gee’s Bend.” History of Gee’s Bend | Souls Grown Deep, www.soulsgrowndeep.org/history-gees-bend. Accessed 7 May 2025.

“History.” Freedom Quilting Bee Legacy, 5 Oct. 2022, fqblegacy.org/history/.

“How a Small Alabama Community Stitched Itself into the History of American Art.” It’s Nice That, www.itsnicethat.com/features/loretta-pettway-bennett-gees-bend-quilt-makers-exhibition-art-131021. Accessed 7 May 2025.

“A Journey of Quilts: How Five of the Famous Gee’s Bend Textiles Came to Mia.” A Journey of Quilts: How Five of the Famous Gee’s Bend Textiles Came to Mia –– Minneapolis Institute of Art, new.artsmia.org/stories/a-journey-of-quilts-how-five-of-the-famous-gees-bend-textiles-came-to-mia. Accessed 7 May 2025.