Aranne Jung has crafted a compelling narrative of resilience in her essay on the haenyeo—South Korean women who free dive for abalone and other shellfish. This remarkable non-fiction piece begins by delving into South Korea’s history, touching on the royal family’s ancient appetite for shellfish, before seamlessly transitioning to the present. Jung expertly highlights the challenges these women now face due to environmental and societal changes. The essay reflects extensive historical research and offers a fascinating read that will captivate readers from beginning to end. –Chuck Bayliss ‘25AC

“The Wild Ginseng of the Sea”: Abalone and Other Shellfish in Korean History and Culture

Aranne Jung ’27

On Jeju Island, a group of women called “haenyeo” (해녀) free-dive to harvest shellfish. Haenyeo, which literally translates to “sea women” in Korean, dive up to 20 feet deep year-round, regardless of freezing temperatures (Sang-hun). One of the most valuable sea creatures the haenyeo harvest is abalone. Known for its exquisite and unique taste, the abalone was often gifted to Korean royals and appeared at special meals. Its value is increased by the abalone’s strong defensive capabilities. The abalone’s “foot,” used to move around and attach to surfaces, is incredibly strong, making it very difficult to harvest: it often requires the use of a harvesting tool (“Abalone: Introduction”). The abalone’s tough shell further contributes to this difficulty (“Natural History”). Even today, abalone divers frequently lose their lives while trying to harvest the stubborn creature (Bland). To minimize the risks, only the most experienced haenyeo, armed with a “bitchang,” dive to harvest abalone (“Jeju Jeonbok”).

The haenyeo are significant not only for their physical feats but for their financial independence and the matriarchal society they have established on Jeju Island as well–a stark contrast to the patriarchal, Confucian society of mainland South Korea (Cawley). However, the significance of shellfish extends further beyond the impressive characteristics and lifestyles of the haenyeo into the entirety of Korean history and culture. Abalone is just one of the many shellfish species in the bordering waters of the Korean peninsula. From a simple food to a form of currency, a radiant piece of delicate art to a symbol of power and independence for the haenyeo, shellfish have a significant presence in Korean history and culture.

First Emergence of Shellfish in Korean History

For the people who first inhabited the Korean peninsula, seafood, including shellfish, was a staple part of their diet. Research has revealed the presence of shellfish in their diet dating back to the Korean Neolithic era, or the Chulmun period (즐문).

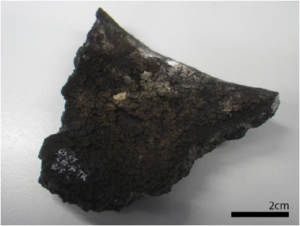

Various sites along the coast of the Korean peninsula contain fragments of Chulmun era (8000-1500 BCE) pottery in shell middens (Kim, Minkoo et al.). This pottery, speculated to be used for specific food storage, reveals traces of food remains–mainly seafood, including shellfish (Shoda et al.). Along with pottery fragments, ancient fish hooks and other fishing utensils have been unearthed from the middens.

One site that provides evidence of both Chulmun pottery and seafood consumption is the Sejuk site, located on the southeast coast of Korea (Shoda et al.). Researchers discovered fragments of Chulmun pottery at the site. An organic residue analysis investigated the residues on these fragments, and cross-referenced their findings with lipids that are frequently found in marine foods. The data showed that the vessels were used to store and cook seafood, which ranged from fish to shellfish. The pottery was discovered along with fishing hooks made of bone and stone, further supporting the likelihood that the Neolithic people relied on seafood. The specific shellfish, however, were the mussels, clams, and oysters found in the shell midden at the Sejuk site (Shoda et al.).

Shellfish in Korean Art

Beyond food, shellfish have served decorative or ceremonial purposes in Korean art and culture. At other archaeological sites, researchers have unearthed seafood shells used to make simple jewelry. For example, at the Ando Site in southern Korea, human remains dating from the Chulmun era have been found with shell bracelets around their wrists (Choy et al.).

The most notable use of shellfish in Korean art is the mother-of-pearl and abalone shells inlaid in najeonchilgi. Najeonchilgi (나전칠기, Korean handicraft employing shell inlay techniques) first emerged around the Three Kingdoms period (57 BC to 688 AD) and was especially popular during the Goryeo Dynasty (918 to 1392). These pieces range from small jewelry boxes to luxurious wardrobes. To create these pieces, artisans take lacquerware and decorate it with carefully chosen and shaped pieces of mother-of-pearl (Chung). Najeonchilgi was popular among Korean aristocrats, and was often gifted to nobles from other countries, indicating how valuable the art was.

However, najeonchilgi was representative of not only wealth, but also the cultural ideals of the time the pieces were created (Lee). Pieces created during the Goryeo Dynasty were influenced by Buddhism, leading to much more intricate and detailed pieces than those produced during the Joseon Dynasty. Najeonchilgi created during the Joseon era reflects the influence of Confucianism on Korean culture and is not as detailed as Goryeon najeonchilgi, embodying the Confucian emphasis of simplicity. The Chulmun jewelry and the long history of najeonchilgi are physical examples of the value and beauty that Korean culture has associated with shellfish.

Shellfish as Currency/Valuable Goods

In the early Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), abalone was frequently presented to the king as a luxurious gift. Its unique taste, rich vitamins, as well as its fleeting freshness made it very desirable (Lever). Various abalone dishes, like abalone porridge and grilled abalone, soon became a favorite dish of the Joseon royalty. It was so valuable that the molluscs harvested from Jeju Island and the southern coast of Korea were often reserved for royalty, and the king desired them to be collected year round–a requirement that would have had important ramifications for the history of the haenyeo (“Jeonbokjuk (전복죽)”). Abalone soon became a form of tax for these people, including the residents of Jeju Island (“Abalone”). In some records from the Joseon Era, over 800 abalone were harvested on Jeju and given to the royal court in one year (이). Those who could not harvest enough abalone were severely punished (Sang-Hun).

Until then, it had been mainly men on Jeju Island who were diving in deep waters for abalone and other shellfish. However, after the king’s order, 8 out of 10 of the men either fled the island or drowned while trying to harvest abalone (“포작인”). This left the women to dive for abalone and to sustain themselves (Chang). A large enlistment in the 1600s also severely lowered the male population on Jeju Island, and the women of Jeju were forced to dive for seafood and shellfish to survive (Mundy). This shift was to herald the following 400 years of the haenyeo’s grueling work.

Even today, abalone is one of the more expensive seafood items. The abalone harvested by haenyeo can sell for as much as 100,000 원 (approximately $76 USD) per pound (Lever).

Although dangerous, diving for abalone and shellfish was an incredibly profitable job during the Joseon Dynasty. The haenyeo were soon able to establish a strong community, women-only organizations, and financial independence (Chang). The Confucian norms that dominated mainland Korea forced women into a patriarchal society, where they were always socially valued below their male relatives (Cawley). However, the haenyeo’s financial independence and secure community defied the Confucian norms, and the women on Jeju Island were even able to divorce and remarry to their liking (Chang).

Shellfish and Haenyeo During the 20th Century

The haenyeo would go on to take their independence and strength and make a significant impact on the history of Korea, ranging from protests during World War II to the rebuilding of Jeju Island’s community after the following turmoil.

During World War II and under Japanese occupation, the haenyeo were able to continue their work. Although they were still profiting, the haenyeo began having to compete with Japanese fishers who overfished the waters around Jeju Island (Kim, Kyubin). Moreover, the local fisheries would give Japanese fishermen an unfair advantage and inadequately compensate the haenyeo for their harvest (“Dark Tourism”). In 1932, as the people’s frustration grew against the invading Japanese, three haenyeo, Kim Ok-nyeon, Bu Chun-hwa, and Bu Deok-nyang, led a large group of over 1,000 residents in a four-month long protest against the Japanese government (Park; Changhoon). The protest was shut down and the three leading haenyeo were arrested and tortured. Today, after the end of the Japanese occupation, the haenyeo’s actions are now honored in a monument on Jeju Island, representing the important role the haenyeo play in the Jeju community.

The turmoil that followed World War II had a serious impact on the overall community and culture of Jeju Island. The people of Jeju disapproved of the US occupation and the division of Korea (Kim, Hun Joon). In 1948, a communist union attacked police stations all across the island. This event, known as the Jeju Uprising or the April 3 Incident, would set off a series of massacres. In the following six years, in an attempt to quell dissent on the island, the Korean government killed over 30,000 people (Kuhn). At the end, Jeju Island was in disarray, with hundreds of villages burned and thousands of people displaced. Yet, Jeju was able to recover because of the haenyeo’s resilience and financial success: annually, the haenyeo’s income made up over 60% of the entire island’s revenue (“The Beautiful Women That Shaped Jeju”).

Today, Jeju Island is regarded as the Hawaii of South Korea, and millions of people flock to the island for coastal vacations (“Jeju Draws All-Time High”).

Current Concerns: Dumping of Nuclear Waste from Fukushima and Global Warming

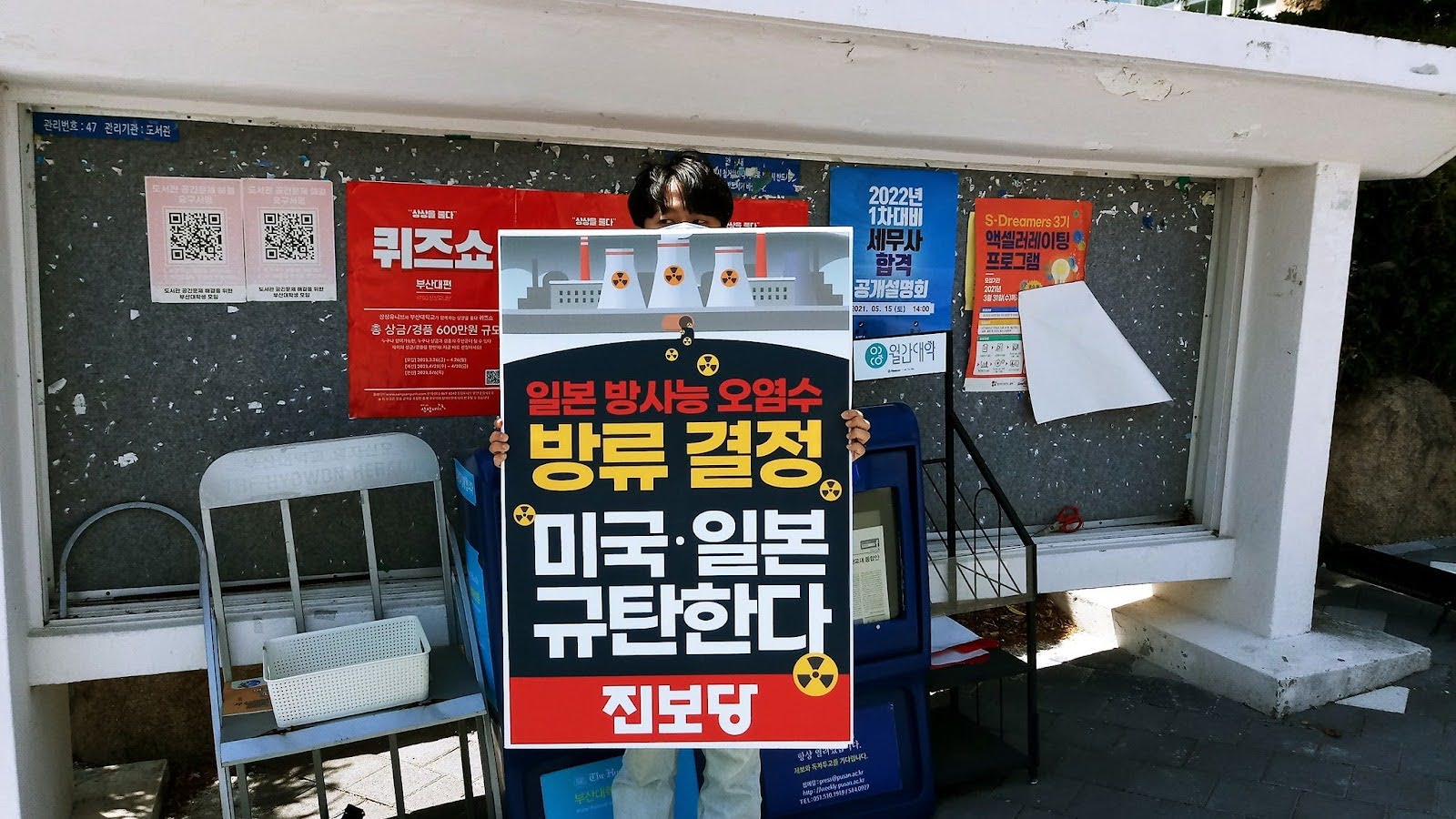

Today, one major political controversy regards the dumping of nuclear waste from the Fukushima nuclear plant in Japan. On August 24, 2023, Japan began releasing treated nuclear waste water into the Pacific Ocean (Wong). This decision has aggravated people surrounding the Pacific, including Korea. In South Korea, many people refuse to buy seafood, as they are concerned about the potential nuclear contamination. Those in the seafood industry are worried about financial losses. For example, seafood vendors in Busan have noted that their sales have been steeply declining ever since Japan began releasing the waste water (Kim, Hyung-Jin).

Although the South Korean government endorsed Japan’s plan, a poll found that over 80% of South Korean citizens are opposed to the dumping of nuclear waste, and many are actively protesting (Kim, Hyung-Jin; Wong). The country already had a ban on imported food products from Fukushima and surrounding areas, but now its people are torn over whether they should continue to purchase seafood (“South Korea Minister Says Import Ban”).

However, the issues concerning the Pacific Ocean extend beyond nuclear waste. The ocean is already under threat from global warming: climate change has affected the harvests of the haenyeo too, who have noted that the amount of seafood they can catch has decreased to only about 13% of what it was before (Kim, Hyung-Jin). The temperature of the waters around Jeju Island has risen by 2℃ (Chun). This temperature change is large enough to introduce harmful coral and sea anemones that are taking over habitat from important algae and kelp that the marine population depends on. Without enough algae and kelp, many fish cannot sustain themselves or find places to live, and shellfish populations that rely on the dwindling algae and kelp populations are also diminishing. The haenyeo are trying to adjust to the changing environment by gearing their diving patterns to breeding seasons, as well as fertilizing the sea, removing garbage from the ocean, and repopulating aquatic species (Kim, Hyung-Jin).

Alongside the waning harvests, the haenyeo themselves are also at risk. At their peak in the 1960s, there were 26,000 active haenyeo (Sang-hun). Today, only a small population of 2,500 haenyeo remains, which continues to lose 200 to 300 members each year. As their population shrinks, their way of life is slowly fading away. Their rigorous and physically demanding work is no longer appealing to current generations, and the majority of the haenyeo are over 60 years old. The lack of seafood and shellfish in the shallower waters forces the women to dive deeper into the ocean, adding to the deadly risk associated with their work. Their cultural importance is not undervalued, however, as they are part of the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage (“Culture of Jeju Haenyeo (Women Divers)”). In an attempt to preserve this profession, the Korean government has implemented financial incentives, and many restaurants on Jeju Island feature meals using seafood caught by haenyeo, and some even provide guests with special seats that allow them to watch the haenyeo work (“Haenyeo Hoetjip”).

Today, as the haenyeo face decreasing membership and dwindling shellfish populations, a vicious cycle has formed. As the smaller abalone and shellfish harvests make it more difficult for the haenyeo to profit and survive off of their work, their traditional work becomes less appealing and slowly fades away, also taking away the haenyeo’s efforts to minimize the effects of global warming on the ocean. Besides their essential contribution to the ocean’s ecosystem, the haenyeo, along with the abalone and other shellfish are an important representation of not only Korean culture but also centuries of history. Not only do these shellfish represent the strength and resilience of the haenyeo, but they define unique and important characteristics of Korean history and culture. From the Neolithic age to the present, shellfish have crawled their way through fragments of pottery, glittering lacquerware, and the demanding economy, and have seen the turmoils and recovery of Korea. These molluscs, and those who harvest them, are an unforgettable piece of Korean history.

Works Cited

“Abalone.” National Maritime Historical Society, https://seahistory.org/sea-history-for-kids/abalone/. Accessed 15 Nov. 2023.

“Abalone: Introduction.” Marine Science, https://www.marinebio.net/marinescience/06future/abintro.htm. Accessed 12 Mar. 2024.

Bland, Astair. “The Most Dangerous Game: Chasing a Sea Snail?” Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/the-most-dangerous-game-chasing-a-sea-snail-65897469/. Accessed 12 Mar. 2024.

Cawley, Kevin N. “Korean Confucianism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/korean-confucianism/>.

Chang, G. “To the Ocean Floor and Back In A Single Breath.” Reader’s Digest. Feb. 2008. https://pressfolios-production.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/story/story_pdf/37632/3763213788835795Tl2lbPpTySiKIZBroRE.pdf.

Changhoon, Ko. “A New Look at Korean Gender Roles : Jeju (Cheju) Women Divers as a World Cultural Heritage :Jeju (Cheju) Women Divers as a World Cultural Heritage.” Asian Women, vol. 23, no. 1, Mar. 2007, pp. 31–54, https://www.dbpia.co.kr/Journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE01107339.

Choy, Kyungcheol, et al. “Stable Isotopic Analysis of Human and Faunal Remains from the Incipient Chulmun (Neolithic) Shell Midden Site of Ando Island, Korea.” Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 39, no. 7, July 2012, pp. 2091–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2012.03.005.

Chun, Kwon-Pil & Kim, Sarah. “Divers, Scientists See Climate Change Altering Jeju’s Aquatic Ecosystem.” Korea Joongang Daily. 23 Sept. 2020, https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2020/09/23/national/socialAffairs/Jeju-Island-climate-change-global-warming/20200923184800417.html.

Chung, Ah-young. “Najeonchilgi.” The Korea Times. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2023/11/178_263142.html. Accessed 15 Nov. 2023.

“Culture of Jeju Haenyeo (Women Divers).” Unesco. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/culture-of-jeju-haenyeo-women-divers-01068. Accessed 15 Nov. 2023.

Darangshi Cave Unearths yet More Jeju Massacre Tragedy – JEJU WEEKLY. https://www.jejuweekly.com/news/articleView.html%3Fidxno=2483. Accessed 10 Dec. 2023.

Dark Tourism: Painful memories of Jeju Island – Korean Independence (Aug. 15) and the Jeju Hangil Anti-Japanese Movement. https://www.visitjeju.net/en/themtour/view?contentsid=CNTS_000000000022463. Accessed 10 Dec. 2023.

“Don’t Dismiss the Fury Over Fukushima’s Water.” Bloomberg.Com, 29 May 2023, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-05-29/nuclear-power-don-t-dismiss-the-pacific-s-fury-over-japan-s-fukushima-water. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

Guha, Nayanika. “Climate Change Is Threatening the Livelihoods of Korea’s Women Free-Divers.” Women’s Media Center, Jan. 2022. https://womensmediacenter.com/climate/climate-change-is-threatening-the-livelihoods-of-koreas-women-free-divers. Accessed 15 Nov. 2023.

“Haenyeo Hoetjip (해녀횟집).” VISITKOREA. https://english.visitkorea.or.kr/svc/whereToGo/locIntrdn/locIntrdnList.do?vcontsId=85211&menuSn=352. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

Haenyeo Memorial | East Coast | Jeju Island | Jeju Province | Korea | OzOutback. https://ozoutback.com.au/Korea/jeju-eastcoast/slides/2014062806.html. Accessed 26 Nov. 2023.

“Jeju Draws All-Time High of 13.59 Mil. Domestic Tourists This Year.” The Korea Times. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2023/12/113_342409.html. Accessed 7 Dec. 2023.

“Jeju female divers a dying breed.” The Korea Herald, 25 Mar. 2014, https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20140325001141.

“Jeju Jeonbok.” Slow Food Foundation, https://www.fondazioneslowfood.com/en/ark-of-taste-slow-food/jeju-jeonbok/. Accessed 12 Mar. 2024.

“Jeju National Museum Exhibits Rare Mother-of-Pearl Lacquerware.” Korea.Net. https://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/Culture/view?articleId=118999. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

“Jeonbokjuk (전복죽).” KBS, Mar. 2018. http://world.kbs.co.kr/service/contents_view.htm?lang=e&menu_cate=lifestyle&id=&board_seq=337109&page=3&board_code=. Accessed 26 Nov. 2023.

Kim, Hun Joon. “The Jeju 4.3 Events.” The Massacres at Mt. Halla, Cornell University Press, 2014, pp. 12–38, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctt5hh0hs.5. Accessed 10 Dec. 2023.

Kim, Hyung-Jin. “In Japan’s Neighbors, Fear and Frustration Are Shared over Radioactive Water Release.” AP News, 24 Aug. 2023, https://apnews.com/article/fukushima-water-release-south-korea-china-2a4dbc409de5322f7205172d2d620535. Accessed 12 Dec. 2023.

Kim, Kyubin. “The Haenyeo and the Sea: Diving As Community-Led Resistance.” YES! Magazine, https://www.yesmagazine.org/issue/bodies/2022/11/21/the-haenyeo-and-the-sea-diving-as-community-led-resistance. Accessed 15 Nov. 2023.

Kim, Minkoo, et al. “Population and Social Aggregation in the Neolithic Chulmun Villages of Korea.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, vol. 40, Dec. 2015, pp. 160–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2015.08.002.

Kim, Soobin. “South Korea’s Forgotten Anti-Communist Killings.” The Dial, https://www.thedial.world/issue-9/south-korea-jeju-uprising-anti-communist-massacre. Accessed 10 Dec. 2023.

Kuhn, Anthony. “Survivors of a Massacre in South Korea Are Still Seeking an Apology from the U.S.” NPR, 7 Sept. 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/09/07/1121427407/survivors-of-a-massacre-in-south-korea-are-still-seeking-an-apology-from-the-u-s. Accessed 12 Dec. 2023.

Lee, Seung-ah. “Jeju National Museum Exhibits Rare Mother-of-Pearl Lacquerware.” Korea.Net. https://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/Culture/view?articleId=118999. Accessed 9 Jan. 2024.

Leong, Lee Kok. “Haenyeo: Celebrating Tenacious South Korean Sea Women.” Maritime Fairtrade, 3 Sept. 2023, https://maritimefairtrade.org/haenyeo-celebrating-tenacious-south-korean-sea-women/.

Letman, Jon. “75 Years After Jeju 4.3 Massacre, Koreans Want a US Apology.” Inkstick. 3 April https://inkstickmedia.com/75-years-after-jeju-4-3-massacre-koreans-want-a-us-apology/. Accessed 10 Dec. 2023.

Lever, C. “Abalone is the ‘Emperor of Shellfish’.” JEJU WEEKLY. http://www.jejuweekly.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=173. Accessed 26 Nov. 2023.

Mundy, S. “The Sea Women of Jeju.” https://www.ft.com/content/e1ec5434-50f8-11e5-b029-b9d50a74fd14. Accessed 26 Nov. 2023.

“Natural History.” Center for Biological Diversity. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/invertebrates/white_abalone/natural_history.html. Accessed 11 Mar. 2024.

Park, Chang-sik. “The 90th anniversary of Jeju Haenyeo Anti-Japanese Movement, and Jeju 4·3.” From Truth to Peace Jeju 4·3, 12 May 2022, http://jeju43peace.org/the-90th-anniversary-of-jeju-haenyeo-anti-japanese-movement-and-jeju-4%c2%b73/.

Shoda, Shinya, et al. “Pottery Use by Early Holocene Hunter-Gatherers of the Korean Peninsula Closely Linked with the Exploitation of Marine Resources.” Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 170, Aug. 2017, pp. 164–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.06.032.

Shoda, Shinya. An example of a typical coarseware ‘Chulmun’ pottery sherd with attached ‘foodcrust’ excavated from the Sejuk sit (USJ08). 2017. Photograph. Quaternary Science Reviews, vol. 170, Aug. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.06.032.

“South Korea Minister Says Import Ban on Fukushima Food to Remain in Place.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSL4N38Q1HY/. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

Sunoo, Brenda. “Jeju Island Haenyeo – Longtime Environmentalists.” Goodee, https://www.goodeeworld.com/blogs/stories/jeju-island-haenyeo-longtime-environmentalists. Accessed 15 Nov. 2023.

The Beautiful Women That Shaped Jeju Into The Beautiful Island We Know Today | Allkpop. https://www.allkpop.com/article/2016/04/the-beautiful-women-that-shaped-jeju-into-the-beautiful-island-we-know-today. Accessed 10 Dec. 2023.

Wong, Tessa. “Fukushima: What Are the Concerns over Waste Water Release?” BBC. 5 July 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-66106162. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

선임기자도재기. “800년 세월 머금은 고려의 빛 돌아왔다.” 경향신문, 6 Sept. 2023, https://m.khan.co.kr/article/202309060952001. Accessed 15 Nov. 2023.

생물권 보전지역. http://www.visitjeju.net. Accessed 26 Nov. 2023.

이상곤. “수라상에 음기를 북돋운 전복.” 동아일보, 25 June 2018, https://www.donga.com/news/Opinion/article/all/20180625/90739634/1.

“제주특별자치도.” 제주특별자치도청, http://www.jeju.go.kr. Accessed 15 Nov. 2023.

포작인 – 디지털제주문화대전. https://jeju.grandculture.net/jeju/toc/GC00702480. Accessed 17 Apr. 2024.

홍영진. “[송수환의 이어쓰는 울산史에세이]왕실 진상 위해 알몸으로 잠수…울산 어부들 목숨 건 노동.” 경상일보, 27 August 2021. https://www.ksilbo.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=911147.

Recent Comments