Drawing on the work of Angela Davis, Mariame Kaba, and Löic Wacquant, Reagan Cobb artfully calls into question the pervasive capitalist invention: the prison industrial complex. Starting with a comprehensive history of the foundations of the PIC, Cobb continues to bare the foundationally exploitative nature of this American system, revealing the incentives of even public prisons to detain people for profit. Challenging the reader to reimagine American society without prisons, Cobb calls all of us into action, not just those with experience with the incarceral system.–Corin Ford ‘26

Breaking the Cycle: The Necessity of Prison Abolition

Reagan Cobb ’28

In the years since the Civil Rights Movement, racism and its deep roots in society have become less easily identifiable. The myth of a “post-racial” society that developed after the election of President Obama only exacerbated this phenomenon. This doesn’t mean racism is any less prevalent, though. One example of its continued influence is the prison system, which disproportionately targets Black Americans. Despite its racist origins and practices, society sees the prison system as a necessary part of American life. The prison system and the resulting prison industrial complex have thus been able to exist relatively unchallenged, despite their destructive nature and ineffectiveness at preventing crime. To stop this form of state violence, it’s necessary to create a society that doesn’t resort to punishment–and the only avenue towards that goal is prison abolition.

The prison system as we know it isn’t simply an institution that happens to disproportionately target Black Americans; rather, it was designed to do so as a form of government oppression and control. According to Loïc Wacquant, the prison system can be seen as the successor to previous forms of racial control, including chattel slavery, Jim Crow segregation, and the “ghetto.” It uses Blackness “as a proxy for dangerousness,” targeting Black communities and attempting to normalize racism by pretending the system is just opposed to crime, and not that it seeks to criminalize Black people (Wacquant 56). The function of the first three institutions was to ostracize and extract labor from Black communities (Wacquant 44, 53). Wacquant argues that the modern-day prison system was born because the “ghetto” eventually failed to ostracize Black communities once the Black Power movement became more widespread (Wacquant 41). The prison system has since evolved into the prison industrial complex, which uses incarceration to extract labor from incarcerated people. Angela Davis defines the prison industrial complex as “the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment” as solutions for social unrest and labor shortages (Davis 43). Its evolution isn’t natural, but is instead born from the desires of the government and corporations that wish to profit off of human suffering. The roots of the prison system are deeply racist, and it will continue to be racist as long as it’s allowed to exist.

Davis similarly argues that the prison industrial complex has created a form of modern-day slavery that targets Black communities, emphasizing its function of extracting profit. This practice started in the wake of the Civil War when prisons leased convicts for labor, since slavery was no longer legal (Davis 94). In the present day, governments pay private prisons for each incarcerated person they hold, giving private prisons an incentive to retain prisoners for as long as possible (Davis 95). On top of that, private companies and private prisons continue to benefit from the exploitation of prison labor, as such a practice is foundational to the prison industrial complex (Davis 84). In the context of the prison industrial complex, or PIC, punishment is not about reforming individuals, but is about finding an excuse to profit from human suffering. The PIC depends on prisoners as “raw materials to guarantee long-term growth,” as it reduces human beings to capital meant to fuel its expansion (Davis 94). Within it, “black bodies are considered…a major source of profit within the free world” while being viewed as disposable outside of the prison (Davis 95). Since it doesn’t see convicts as people, the prison industrial complex will ensure these prisons are filled, with or without justification. Conditions within private prisons are notoriously poor despite the significant profit they generate, demonstrating a distinct lack of care for human life. Even public prisons are fueled by greed, as they’ve become a market for private corporations, whether that be companies that sell cleaning solutions, network companies, or healthcare providers (Davis 99, 100). Exploitation is foundational to the PIC, as it has always been its primary purpose.

The targeting of Black communities that makes up the foundation of the prison system has created a vicious cycle that continuously feeds new people into prisons. When people go to prison, they lose access to valued “cultural capital” such as education and funding for that education. They are also excluded from “social redistribution and public aid” such as welfare and food stamps, and are banned from political participation (Wacquant 57). It’s also much more difficult to obtain a job with a criminal record, not to mention the years that people are unable to work and accrue wealth while in prison. As a result, formerly incarcerated people are much more likely to struggle financially, which can necessitate turning to illegal means for financial support. This then increases the risk of returning to prison, and the cycle repeats. Their financial struggles will then be passed down to their children in a world where basic necessities are increasingly expensive. Black people are incarcerated at disproportionate rates, and on top of that, formerly incarcerated Black people lose “nearly $100,000” more in lifetime earnings than formerly incarcerated white people (Bunn et al. 197). The difficulty of escaping the cycle becomes even clearer in the context of the already-existing income disparity between Black communities and white communities.

Americans accept the prison system without questioning it, thus facilitating its continued existence. The average person considers the prison to be an inherent part of life, making it difficult to imagine that there could be alternatives (Davis 9). Instead, society imagines incarceration as a fate for “others”–typically people of color–that deserve such a fate (Davis 16). If people do manage to imagine a world without prisons, they often reject the idea because of a misinformed notion that prisons reduce and prevent crime; in reality, prisons have very little effect on crime rates (Kaba). Reform is often proposed as a solution to the issues the prison system presents, but such efforts only reinforce the imagined immortality of the prison system, failing to suggest improvements that don’t include its continued existence. Any ideology, including reform, that advocates for anything but the abolition of the prison system fails to ask the necessary questions to contend with the reality of incarceration. Non-incarcerated Americans must engage with the societal problems created by the prison industrial complex instead of just brushing them off because they don’t directly affect us.

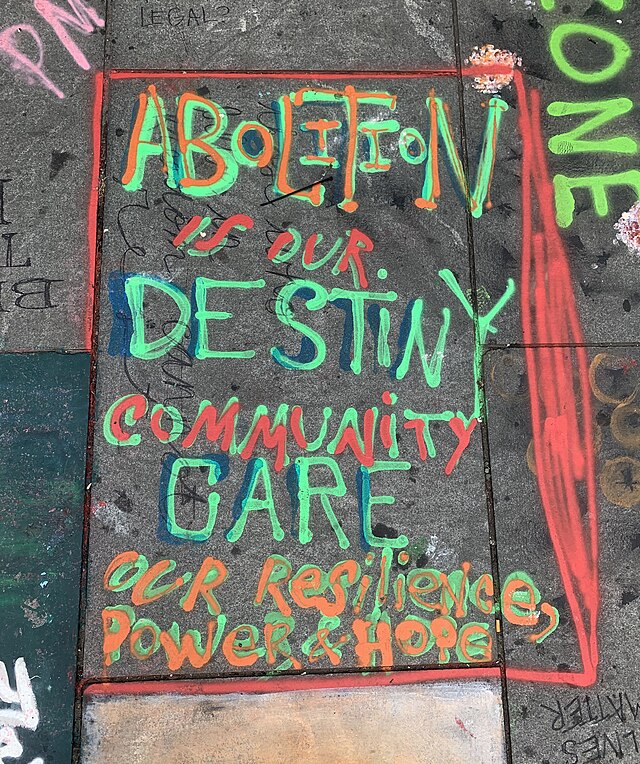

power, and hope.” Wikimedia Commons.

Prison abolition is not an easy solution to the prison industrial complex, but no other productive solutions exist. Abolition will require fundamental changes to society, such as deconstructing the attachment to punishment as a fundamental part of achieving justice (Davis 107). In reality, punishment obstructs justice by normalizing and perpetuating violence. A society without prisons will have to treat those who have done harm as people, instead of dehumanizing them within the prison industrial complex. Punishment is not the natural successor of crime: It is instead linked to political agendas and corporate greed, despite the popular narrative that the government has created (Davis 112). Punishment isn’t beneficial to society either; it allows us to abandon the work of forgiving each other, or at least letting go of our anger. Deconstructing the narrative surrounding punishment allows us to build a society where harm can be addressed outside of the systems that only serve to perpetuate it (Kaba). It can be difficult to move away from our attachment to retaliation, especially when it comes to violent crimes, but inflicting more suffering is never a good solution. Creating “a world without harm” is impossible, but working towards a less violent and more forgiving world isn’t (Kaba). Focusing efforts on education, healthcare, and support for those that need it–especially those that deal with mental illness–is essential to building such a world (Davis 108). In fact, efforts to prevent harm and support victims will be much more productive at addressing crime than punishment could ever be. Building a world outside of the prison system is not only entirely possible; it is necessary for creating a better world.

The prison system was created as a form of social control, one that was engineered to disrupt movements that were seeking social and political progress for marginalized groups. In doing so, it created significant barriers to organizing against itself. The prison industrial complex evolved from the prison system as a way to extract profit from the people who were trapped in the vicious cycle created by incarceration and its consequences. It is not enough to simply reform the existing system, as it is founded on racism and outdated ideas of punishment in connection to crime. A foundational restructuring of American society will have to take place, as a truly just society cannot exist in tandem with the US’ current justice system; its purpose has never been to enact justice but to instill fear. There can be no true progress when there are people left behind, and that includes those trapped behind bars.

Works Cited

Bunn, Curtis, et al. “Locking Up Black Lives.” Say Their Names, Grand Central Publishing, 2021, pp. 193–97.

Davis, Angela. Are Prisons Obsolete? Seven Stories Press, 2003.

Kaba, Mariame. “So You’re Thinking About Becoming an Abolitionist.” Medium, 30 Oct. 2022, https://level.medium.com/so-youre-thinking-about-becoming-an-abolitionist-a436f8e31894.

Radomianin. “A picture of the Alcatraz recreation yard and dining hall building in San Francisco, CA.” Photograph. Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Ratto, Andrew, “Abolition is our destiny community care our resilience, power, & hope.” Photograph. Wikimedia Commons, 7 July 2020.

Wacquant, Loïc. “From Slavery to Mass Incarceration.” New Left Review, 13 (February 2002): 41–60.

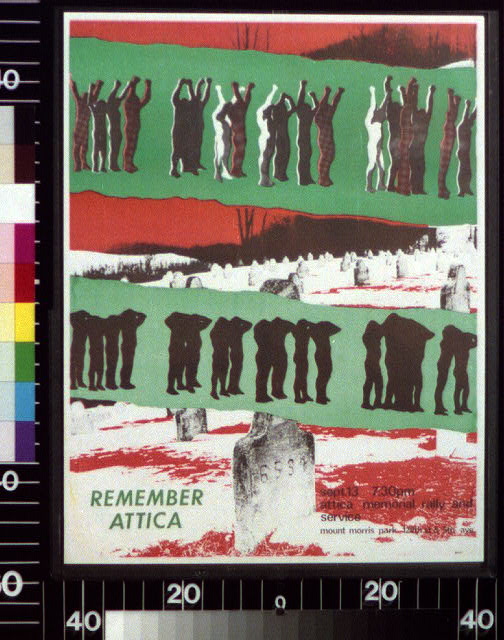

Yanker, Gary. “A poster made in the wake of the 1971 Attica Prison Uprising.” Library of Congress, “Remember Attica,” 1971.

Recent Comments