In their compelling analysis of Claudia Rankine’s book-length poem Citizen, Moby Yang transforms the literary element of second-person address into a tool for reconstructing the identity of the reader. Examining the distance between white reader and Black subject, they argue that by placing “you” in the uncomfortable and disorienting experiences of Blackness, Rankine forces readers to forfeit the separation of their individual self. Ultimately, Yang positions reading as a liminal experience where, in grappling with this uncomfortable intimacy, we might reimagine ourselves as members of a collective whole.–Kokwe Dadzie, ‘26

Can You [See Find Place] Yourself Inside Me? The Shifting Intrusions and Intimacies of Solidarity in Citizen

Moby Yang ’28

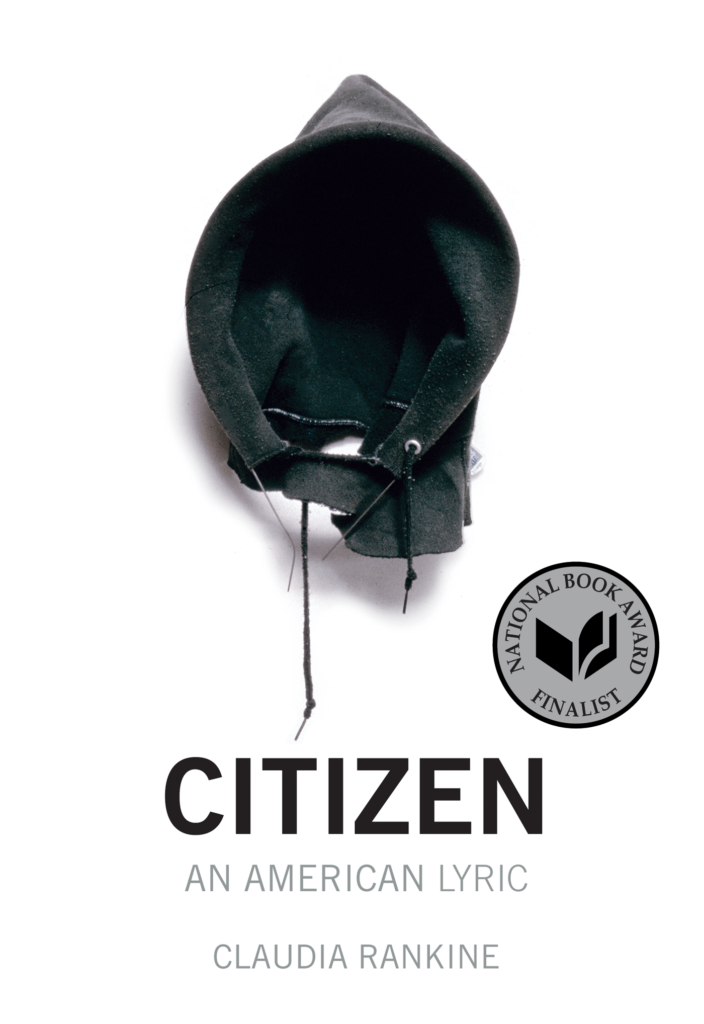

In subtitling Citizen as “An American Lyric,” Claudia Rankine situates her text in a predominantly white canon of post-Romantic lyric poetry traditionally embodied by the first-person “I,” the individual subject—the white subject—who voices their private, interior experiences to an audience distinctly separate from themselves as a speaker. Indeed, the singularity of the lyric “I” is intertwined with the assumed normativity of whiteness. As Kamran Javadizadeh describes in his analysis of Rankine’s reimagined lyric subject, the white writer and the white lyric subject’s “implicit claims to universality and unmediated identity” have fueled the “historical consolidation of a normative lyric,” an “all-encompassing” white “I” that, in actuality, is only built by and for white bodies (476). Thus, against this racially homogenized historical backdrop of the lyric genre, what role does the speaker of Rankine’s Citizen fulfill? Who is the “American citizen” her poem is written through? The expectation is the white citizen, the white lyric subject who—secure in a world that grants them agency to choose when and when not to share themselves with the public, or in other words protects their privacy and interiority—confesses their inner thoughts, emotions, and ideas while retaining a bounded distance from the audience. With Rankine’s subversive second-person address, however, Citizen disrupts the white lyric tradition by uprooting “you” from individual privacy and relocating “you” in a collective public—one where we belong not just to ourselves, but to each other. By blurring the bounds of our identities as readers and citizens, subjects of the lyric and nation, Rankine speculates a future where we might join hands in ever-shifting solidarity—if only we open ourselves to our inevitable intrusions upon and intimacies with one another; if only we embrace the necessary vulnerability of such a shared world.

If the canon of lyric poetry—and indeed the history of the American nation—supports the protected privacy of the white subject, then it is important to understand the conversely unstable privacy of the Black subject. Rankine, quoted in Javadizadeh’s article, notes how difficult it is for her to see herself in sole isolation: “As a black person, it’s difficult not to understand that you are part of a larger political and social dynamic” (476). Being a Black poet, Rankine isn’t afforded the same easy autobiographical freedom and singularity that a white poet like Robert Lowell enjoyed in his poetry, which has long been acknowledged as representative of both confessional poetics and the (white male) lyric tradition (Javadizadeh 476). Javadizadeh argues that it is “Harder, after all, to ‘say what happened’ when the sovereignty of the subject (the whom that ‘what happened’ had happened to) had been called into question, when the poet’s self was thought of not as… internally coherent… but instead as a linguistically—and therefore in Rankine’s view, socially and politically—contingent and shifting site” (476). Without the “sovereignty of the self” of the white subject, the Black body bears a disproportionate burden of placelessness and disorientation in a world built only for white stability and coherence. In order to introduce the isolated white reader into this collective world that the Black subject must already navigate, Rankine therefore embodies the lived disorientation of Black and marginalized bodies into a literary, imagined disorientation for a predominantly white audience through her destabilizing second-person address.

In order to understand Rankine’s linguistic break-down of the bounds of her reader’s identity, it might be helpful to consider Sara Ahmed’s analysis of “disorientation” in Queer Phenomenology. Of particular interest to Citizen’s second-person “you” is Ahmed’s illustration of the “ordinary” disorientation of someone calling out your name:

You look up, you even turn around to face what is behind you… you move out of the world, without simply falling into a new one. Such moments when you ‘switch’ dimensions can be deeply disorientating. (Ahmed 157-8)

Paralleling someone “[calling] out your name,” Rankine’s second-person address to “you” also emulates a disorienting “switch” of dimensions. When she calls out “you,” she sweeps you off the stable ground of your privacy as a white reader—she “moves you out of your world,” and rather than let you “simply fall into a new one,” she “switches” you into racially “foreign” bodies and experiences, uncomfortable worlds for which you must forsake your individuality in order to orient yourself in, worlds that—in a turn of events—are now neglectful of your whiteness. Given the imperative nature of the second-person address, Citizen opens with commands over your imagined body: “When you are alone and too tired even to turn on any of your devices, you let yourself linger… You smell good. You are twelve… You can’t remember…” (Rankine 5). Notably, it is not just your actions that Rankine commands, but your identity, too; she soon makes it clear that “you” are Black, and in this first section she narrates “your” recollection of several distinct memories of racist microaggressions—from a girl at Catholic school telling you “you smell good and have features more like a white person” to your new therapist screaming at you to get away from her house (Rankine 5, 18). Thus, from the very beginning of Citizen, Rankine dislocates you from your own body and relocates you into a racially distinct “other.” You find, suddenly, that “you” do not belong to yourself anymore. Though you might enter Citizen under the assumption that you as a white reader will keep a safe distance from the Black subject of the text, Rankine quite literally calls “you” out and collapses that very distance. By addressing you directly as the subject, she breaches your isolation; by disorientingly “switching” you into a racially foreign body, she destabilizes your solid sense of self and your hold of privacy. In order to reorient yourself, Rankine invites you to attempt a kind of strange intimacy—to navigate a new “you,” to place yourself inside of someone else. Reorientation, then, goes hand-in-hand with attempting to locate within a foreign body—the Black body, the “non-citizen”—something to connect with, to latch yourself onto. Though this strange intimacy is limited only to imagination, Rankine’s second-person address takes the first step in de-individualizing “you,” the reader, by pulling you out of your isolated position as an external spectator and bringing you directly into the subject position of the “other.”

Once Rankine sways you to dissolve your guarded interiority as a reader, she is then able to reconfigure “you” as a constantly shifting figure. By asking you to imagine yourself in all kinds of foreign bodies—not just “other” in race, but also “other” in guilt—she implicates your body as a collective rather than individualist actor intertwined with the historical memory and legacy of racism. In a sharp departure from the “you” of Citizen’s opening section, Rankine directs her second-person address in the script for the “Situation” video made in memory of James Craig Anderson to Anderson’s killer, Deryl Dedmon. In this section, when Rankine addresses you as someone you are not, and as someone who is guilty—“Do you recognize yourself, Dedmon?”—when she voices your apology, your anger—“You are so sorry. You are angry, an explosive anger”—and detonates that anger inside you—“So angry, an imploding anger”—the experience is inherently disorienting (94-5). You are, of course, not Dedmon. But Rankine seems to be asking, can you imagine yourself in his body? Can you see—even if for just a moment, this moment where you occupy Rankine’s “you”—that you are part of something more than yourself? That you too might share the responsibility of his violence? As Javadizadeh succinctly observes, by “distributing” her second-person address “across… a wide range of anecdotes,” Rankine configures a constantly shifting “you” that blurs the solid borders of “your” identity (482). Rather than deflect collective responsibility by positioning yourself as an individual actor, she urges you to locate yourself in a jarringly disparate body; she transposes you into the burden of someone else’s violence, a violence that—given the racism built into our nation’s past and present—you share. Just as the racially marginalized body is constantly denied interiority and must recognize themselves as “part of a larger political and social dynamic,” so too does the white reader now grapple with the dislocation of themselves from their previously respected boundaries; they too are relocated into a disorientingly shared world, and in particular, a world whose violence they play an active role in.

Even so, this public into which Rankine places herself, “you” the reader, and all the figures of Citizen—is shaped not just by the risk of violence, but also the potential for understanding. In this liminal space where true privacy is perhaps impossible, Rankine suggests that we all belong to some extent to each other; we exist, and therefore must navigate ourselves and one another, in a collective where intrusion and intimacy are inevitable and intertwined. Rankine interrogates this interpersonal navigation in “Making Room,” where she captures “your” effort to understand the man sitting alone—his character also a variable, shifting figure—and imagine what he is thinking: “You sit next to the man on the train, bus, in the plane, waiting room, anywhere he could be forsaken. You put your body there in proximity to, adjacent to, alongside, within” (131). Notably, Rankine draws out the placelessness of both the man and “you,” in the physical setting of your bodies, which could be “anywhere” he is “forsaken,” as well as in the figurative map of your intimacy with each other as strangers. “You” must figure out where to orient yourself to him in order to fill the space around him—the physical unoccupied seat and his social isolation. Moreover, the placement of your attempted intimacy is itself uncertain, shifting not only around the man—“in proximity to, adjacent to, alongside”—but possibly stepping “within” him. That your well-intended empathy might cross the boundary of the man’s private body, might become intrusive, or even violent, is brought into focus in yet another indeterminate exchange: “Does he feel you looking at him? You suspect so. What does suspicion mean? What does suspicion do?” (Rankine 132). These questions, which go unanswered, invite you to “struggle against the unoccupied seat” around the man and intensely interrogate your wish for intimacy with him (Rankine 131). Just as your body does not exist in isolation, Rankine makes it clear that your attempt to connect with the stranger, to latch onto the marginalized Black body, also exists in a larger political context; given the history of Black surveillance, your “looking at him,” even if born out of a desire for connection, blurs the lines into “suspicion,” into what Chad Bennett calls a “demand for transparency,” for access into the Black subject’s interiority (395). In a world that has historically threatened Black people’s autonomy over privacy and marginalized people’s sovereignty over themselves, Rankine calls upon us to recognize how intimacy inevitably risks intrusion and to recognize the injury laden in our conflicting desires to both protect our interiorities and forge solidarities, to reach for each other in times of need.

Exploring and tending to this injury, Rankine settles us in an ultimately unsettled and indeterminate site of connection as a way to acquaint us with both the limits and necessities of solidarity. Crafting the last section of Citizen with a placeless yet intimate second-person poem that seems to grapple with the boundaries of “you,” Rankine explicitly names the deindividualization “you” have experienced in reading Citizen, how your grasp of yourself and your privacy has loosened in the collective she has opened you to: “Soon you are sitting around, publicly listening, when you hear this—what happens to you doesn’t belong to you, only half concerns you… It’s not yours. Not yours only” (141). In particular, Rankine draws out the disorienting shock and visceral pain of realizing the sharedness of your “self” through her descriptions of the body as an interior that—despite desiring and deserving protection—is always trespassed by others, the body that is “entered as if skin and bone were public spaces,” the body which is supposed to be the “safest place” to hold your living (144, 143). Especially for the racially marginalized body whose self-sovereignty is constantly denied, Rankine gives voice to the contradictory desire to both belong to yourself in shielded privacy and yet be called upon—be seen—by others: “To be left, not alone, the only wish— / to call you out, to call out you. / Who shouted, you? You / shouted you, you the murmur in the air, you sometimes / sounding like you…” (145). In recognizing this desire for an isolated self, Rankine suggests that we can look at our privacy and opacity not as wishes “to be left… alone,” but as wishes to exist on our own—on your own—to be able to make out a singular “you” that “[sounds] like you.” Even as we wish to protect and respect each other’s interiorities, Rankine highlights our simultaneous need to understand and be understood by one another, to reach for solidarity even as it inevitably blurs the lines between intrusion and intimacy, between the dual connotations of “calling you out” and “calling out you.” Strikingly, Rankine ends this initial poem of Citizen’s seventh section on a point of intense and unresolved pain: “The worst injury is feeling you don’t belong so much / to you— ” (146). She emphasizes once again the inescapable sadness and “injury” to the reality of our shared existence, that we belong never wholly to ourselves but to each other, that we must be offered to and entered by one another—and that entering can be intimate, and that entering can be violent, and that entering, whether intimate or violent or both, can perhaps never truly be confirmed. As Rankine ruminates on the inevitable yet opaque and oblique accessibility of our bodies to one another, she invites us to consider how we should find each other in the disorientingly placeless uncertainty of our connection, how we might forgive our missteps between intrusion and intimacy to come together in solidarity.

Having done the work of disorienting “you,” the reader, in your reception of Citizen, having opened you to the unstable sharedness of your body, which navigates the indeterminate bounds of other bodies, Rankine seems to convey that the solidarities we form must similarly shift in constant flux. In Queer Phenomenology, Ahmed writes that “moments of disorientation… are often moments that ‘point’ toward becoming orientated,” and in Citizen, this moment of reaching for reorientation of our non-sovereign and placeless bodies is demonstrated at the close of “Making Room” (Ahmed 159). In Rankine’s script, even though “you” have been intensely aware of the ambiguity of your imagined intimacy with—or intrusion upon—the man sitting beside you, the scene ends on a striking moment of connection: “It’s then the man next to you turns to you. And as if from inside your own head you agree that if anyone asks you to move, you’ll tell them we are traveling as a family” (133). Despite the inaccessibility of your inner thoughts to each other, you envision a solidarity where you and the man “[travel] as a family,” where you might stabilize each other in case you are threatened with further displacement—in case someone “asks you to move.” Notably, this temporary connection is bridged by shared action; you both turn to face each other, and you both would, potentially, travel together. Indeed, “your” speculation of reorientation through connection here is not fully realized, heard only “from inside your own head,” unconfirmed by the “other” body that you attempt to latch onto. Given that they are fated injuries of our shared world, Rankine does not—or rather, cannot—offer a complete remedy to your disorientation and placelessness. Instead, the temporary solidarity you imagine in “Making Room” is indeterminate and forever-shifting, a connection that is itself dislocated in the movement of “travel.” Still, for a moment, you and the man turned your heads to each other; for a moment, you found yourselves in each other. Perhaps some new connection has been bridged—an in-progress solidarity constrained by the limits of our simultaneous intrusions and intimacies; a solidarity spontaneously formed, earnestly imagined, and still in motion.

By directly calling out and addressing “you” in your reading of Citizen, Rankine implicates you in the shared nation of her “American Lyric.” Rankine’s linguistic breakdown of the bounds between her reader and herself, of “you” and “I,” intentionally pries apart and calls into question the viability of privacy—and in particular, the protected interiority of the white reader—in a collective where we must share each other’s violence and reach for one another in solidarity. Despite our desire to belong to ourselves, in order to meet, connect, and support each other in the public, we must forsake our absolute hold of the private—we must open ourselves up to the possibility of being trespassed, the risk of trespassing others. And yet, this recognition of solidarity’s instability only goes so far; Rankine seems unable to offer a realized vision of what our formations of connection should look like, only pointing to brief, dispersed speculations, imaginations of how we might “travel as a family.” This constrained speculation might be intentional; as a poem and a text, Citizen cannot achieve any tangible action, and even Rankine’s subversive “you” is only an intimate intrusion within the figurative, linguistic world of her text. Instead, perhaps Rankine makes use of the liminal experience of reading by emulating the similarly liminal disorientation of destabilizing her white reader’s sense of coherent “self.” From there, she compels you to turn your discomfort into action, to reach out into the real world even as you bear the injuries of such a vulnerable openness. Only then, perhaps, can we truly reorient ourselves—move beyond the page, move beyond mere imaginations of solidarity—and join hands.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. “CONCLUSION: Disorientation and Queer Objects.” Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others, Duke University Press, 2006, pp. 157–80. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv125jk6w.8. Accessed 9 May 2025.

Bennett, Chad. “Being Private in Public: Claudia Rankine and John Lucas’s “Situation” Videos.” ASAP/Journal, vol. 4 no. 2, 2019, p. 377-401. Project MUSE, https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/asa.2019.0018.

Engin_Akyurt. “Train, Wagon, People Image.” June 6, 2017. Pixabay. Open source. https://pixabay.com/photos/train-wagon-people-crowd-feet-2373323/

Javadizadeh, Kamran. “The Atlantic Ocean Breaking on Our Heads: Claudia Rankine, Robert Lowell, and the Whiteness of the Lyric Subject.” PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 134.3 (2019): 475–490. Web.

Rankine, Claudia. Citizen: An American Lyric. Graywolf Press, 2014.

Recent Comments