Siobhan Dietz’s essay on a woman who lived through a critical point in history shines as necessarily grounding in our present moment. Though Siobhan met Dorothy through reading her diary entries, her potent analysis and critique of modernism supported by archival research explores what it means to be a “Smithie,” highlighting the themes and tenacity we relate to as students with a unifying identity. Ultimately, the piece leads us to question the tensions we feel in the world we inhabit and lends us ideas on how to navigate uncertainty. –Madeline Turner ’21, Editorial Assistant

Dorothy Dushkin and the Modernism of Smith College in 1925

Siobhan Dietz ’23

Diaries are where we record our most personal thoughts and provide a vivid description of the time in which the diary was written. If archived, they allow the reader to step back into the age of the writer and almost experience the writer’s life. When Dorothy Brewster Smith Dushkin graduated high school, her father gave her a black leather diary which she took with her to Smith College. Roughly 100 years later, as a Smith student myself, I came across this diary, and it gave me a glimpse into the culture of historically women’s colleges. I learned about the ambitions and values of an exceptional young woman taking advantage of the new possibilities for her gender that emerged in the 1920s. In reading Dorothy’s diary, I realized how Smithies have always been pushing the limits of societal norms. The actions of revolutionary women such as Dorothy are the foundation of the liberal social culture in which we live, and they continue to remind us that we must push the limits to improve the world for women to come.

Dorothy was born in 1903 to Henry Smith and Nellie Judd in Glencoe, Illinois. She spent her final two years of high school studying music at Bradford Academy, located outside of Boston, before moving on to Smith. She journaled from ages 15-85, but I focused particularly on January through September 1925, which encompassed her final semester at Smith as well as her introduction into independent adulthood.

Dorothy was born in 1903 to Henry Smith and Nellie Judd in Glencoe, Illinois. She spent her final two years of high school studying music at Bradford Academy, located outside of Boston, before moving on to Smith. She journaled from ages 15-85, but I focused particularly on January through September 1925, which encompassed her final semester at Smith as well as her introduction into independent adulthood.

Through reading her diaries, I gained both a friend in her and a thorough understanding of what a college student at the same place as me experienced 100 years ago. The diaries give us a rich sense of this particular woman and the culture of which she was a part – one that was progressive and Modernist, especially the music culture. Life at Smith College in 1925 connects exceptionally well to Lynn Dumenil’s definition of “the new woman” – “a symbol of modernity itself” (98) – yet such life was also not immune to the broader Victorian social culture. Despite the conservative elements of the college, such as the pressure to marry and enter a domestic lifestyle, Dorothy resisted and criticized them, demonstrating how she was especially a “new woman” within the Modernist movement.

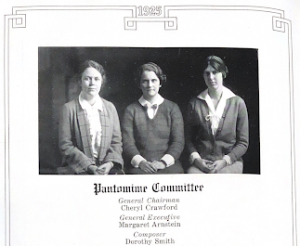

Dorothy spent her time at Smith as a music major, throwing herself into the student-created culture on campus. She had many musical accomplishments while at Smith, especially when it came to composing. She composed the music for a pantomime play that was part of the Commencement program, which she notes as a nearly daily activity during the second half of her senior year; she was awarded Honors for this triumph by the music faculty. Also for Commencement, she composed two songs for the Ivy Song Program, which got stellar reviews in The Smith College Weekly, the college newspaper. She was a prolific composer throughout her life, but Smith was where she truly got her start, partially through a composition  organization called Clef Club. Female composers at the time were rare, and this rarity in musical culture has persisted through today. She used her compositions as the beginning of her career, noting a visit to a publisher in Boston to discuss copyrights on January 26, 1925. It became clear to me after reading just a few entries that music was her life’s passion, and the music culture at Smith that was largely driven by the students allowed her to flourish within the role of composer. Her descriptions of this independence provided me with valuable knowledge of how women’s colleges empower their students. While the social culture of the time promoted women residing within domestic roles, women’s colleges gave their students the opportunities to occupy all forms of leadership, furthering their ambitions for success that were entirely Modernist in their existence.

organization called Clef Club. Female composers at the time were rare, and this rarity in musical culture has persisted through today. She used her compositions as the beginning of her career, noting a visit to a publisher in Boston to discuss copyrights on January 26, 1925. It became clear to me after reading just a few entries that music was her life’s passion, and the music culture at Smith that was largely driven by the students allowed her to flourish within the role of composer. Her descriptions of this independence provided me with valuable knowledge of how women’s colleges empower their students. While the social culture of the time promoted women residing within domestic roles, women’s colleges gave their students the opportunities to occupy all forms of leadership, furthering their ambitions for success that were entirely Modernist in their existence.

Although the college was very socially progressive, some Victorian elements of 1920s culture existed within the college, such as religion. In 1925, Smith was religiously-affiliated and held weekly chapel, which was used as a sort of assembly for the student body where the administration could make important announcements, as Dorothy describes it. She also notes that the town of Northampton “closed” on Sundays because the community was so religious. Smith itself didn’t necessarily impose religion upon its students, but having a spiritual life was a more prevalent social value in the 1920s and seen as important for a well-rounded woman. Religion was more closely associated with Victorianism, but remained a pillar of culture through the Modernist revolution.

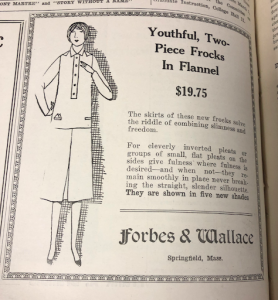

While emphasis on religion was a more old-fashioned element of women’s colleges in the 1920s, a progressive aspect was the students’  adoption of the latest clothing trends. An essential part of my research was The Smith College Weekly, which gave me insight into the types of messages college women received at the time. The ad to the below was found in the collection of 1924-1925 issues and promotes clothing trends of the time. As women began to gain more independence, hemlines came up and waistlines came down, giving them physically more freedom in their clothing. This was one visible implementation of the shift from Victorianism to Modernism, as the modest clothing of earlier decades was abandoned for a more boyish look. Since college-age women were the ideal market for these progressive clothing styles, it is entirely natural it would be advertised in a college newspaper, and in all the images of Dorothy and her friends I found, they wore clothing nearly identical to this image.

adoption of the latest clothing trends. An essential part of my research was The Smith College Weekly, which gave me insight into the types of messages college women received at the time. The ad to the below was found in the collection of 1924-1925 issues and promotes clothing trends of the time. As women began to gain more independence, hemlines came up and waistlines came down, giving them physically more freedom in their clothing. This was one visible implementation of the shift from Victorianism to Modernism, as the modest clothing of earlier decades was abandoned for a more boyish look. Since college-age women were the ideal market for these progressive clothing styles, it is entirely natural it would be advertised in a college newspaper, and in all the images of Dorothy and her friends I found, they wore clothing nearly identical to this image.

Though students found empowerment and support at women’s colleges, the world that waited for them post-graduation was less welcoming. Dorothy had to resist many pressures from the conservative social culture that attempted to relegate her to domestic activities. Like many college-educated women of the time, she was offered a teaching position. She ultimately turned down the job in hopes of higher career ambitions, but many other women in the 1920s sought out teaching as their career. It is estimated that 8 out of 10 teachers in the 1920s were women, due to the prevailing belief that women’s primary role was in the home and that teaching was the closest career to domesticity. Despite the independence women could gain through a college education, they were most likely going to enter domestic life in some form; Dorothy lamented that so many of her peers might not use their education.

The other considerable pressure that weighed on female college students was that of marriage. In the early twentieth century, college-educated women married much later in life or not at all, but Dumenil writes that “by the 1920s, that trend had been reversed and educated women increasingly married” (124). Dorothy certainly felt the social pressures to get engaged while on campus, noting that at her class supper post-graduation, “too many people [got] engaged. 10% of the class – a large percentage.” Although the women who attended Smith were already forging new life paths for themselves, they could not be fully immune to societal expectations once they graduated. This expectation for marriage and withdrawal into domestic life remained a distinctly Victorian outlier of the Modernist 1920s.

Throughout the part of her diary that I read, Dorothy didn’t mention any interest in marriage or suitors until the months after she had graduated, and even then she didn’t seem committed to the idea of marrying yet. However, she did make a friend in Christopher Thomas, a married man she met during summer work at a music school in Concord, NH. Thomas gave Dorothy a “much clearer idea of the other sex,” and her writing about him marks the time when she begins noting her interest in men in her journal. Of Thomas, she writes that she wished “it were possible for a married man to write to another woman without conventional censure.” Dorothy’s sense that marriages were so fragile that they could not tolerate partners’ friendships with members of another sex is certainly a Victorian value that was carried into the twentieth century. She tried to ignore this, but such conservatism lingered over the modernizing world along with the expectation that women would have lives of marriage and domesticity–particularly antiquated characteristics of the time.

Throughout her diary entries, Dorothy emerges as a skeptic of many commonly held thoughts. She finds the excessive consumerism that arose in the 1920s to be particularly corrosive to American culture, in contrast to the majority of the country that supported it. Of advertising she writes, “I should hate it – forcing my product upon people etc. The market is so overcrowded with unessentials all ready.” This fits with Dumenil’s characterization of the 1920s, where she discusses the consumer culture that erupted, particularly aimed toward women who were beginning to have more autonomy over money. Dorothy was also wary of the line between patriotism and nationalism. On one occasion she went to see the 1924 silent film Peter Pan, critiquing the Americanized Lost Boys. She notes it as being “displeasing” that they were American patriots and sang the national anthem instead of leaving politics out of the movie. Of course, this was an attempt to encourage national pride post-WWI, but Dorothy found it to be an unnecessary addition to the movie because it promoted American Exceptionalism and she could sense its potential destructiveness.

While national unity was being promoted on a country-by-country scale at the time, many women of the 1920s, Dorothy included, looked towards a higher international peace and unity as a form of healing for the world post WWI. Dumenil makes note of this, writing about how women’s sensitivity that was required for them to be mothers led them to be deeply involved in the peace movement during the interwar years. Dorothy was involved in the peace movement, and had high hopes for how the world’s wrongs could be remedied. She says:

I’m sure that my generation will do something for international peace + enlightenment for we have a real honor of war + we’ve been taught somewhat differently in matters of history than our parents.

Of course, now we know that instead of international peace, there was WWII, but the sentiment of hoping that the world’s leaders could learn from past experiences is still important. My generation is facing a similar struggle. The US has been in constant war for my entire life and the hope that history could help inform the decisions of world leaders still remains. Dorothy believed that because her generation lived through one war, they would certainly not allow it to happen again. She doesn’t further write about peace, but combined with her other socially liberal views, I can understand how she and other college students occupied a certain level of social isolation from the rest of nationalized America.

Through the diaries of Dorothy Brewster Smith Dushkin, we get the sense of a lively and autonomous student culture at Smith College – one that is very Modernist in its values. We also see some elements of Victorianism as more conservative social institutions such as religion and marriage begin to weigh upon the student body. Dorothy herself emerges as a questioner of the conservative trends both within the college and society, and she stays true to her beliefs in her future life. After Smith, Dorothy went to France to study music under Nadia Boulanger, where she met her husband David Dushkin. They married in 1930, and although many of her classmates resigned themselves to domestic life after marrying, Dorothy and David found a way to merge marriage and career. They went on to form the Music Institute of Chicago and various other music institutions together until David’s death in 1986. Dorothy’s diary gave me access to a young woman who embraces the questioning we now associate with Modernism, providing me with an extra layer of depth as I seek to understand the demographic of women whom we’ve studied. Dorothy was a revolutionary for her time, becoming the type of woman we now associate proudly with the word “Smithie.”

Works Cited:

Dumenil, Lynn. “The New Woman and the Politics of the 1920’s. OAH Magazine of History, Volume 21, Issue 3, July 2007, Pages 22–26, https://doi.org/10.1093/maghis/21.3.22.

Smith College Weekly – Smith College newspaper, 1924-25, College Archives, Smith College Special Collections.

Smith College Course Catalog, 1924-1925, College Archives, Smith College Special Collections.

Smith College Yearbook, 1924-1925, College Archives, Smith College Special Collections.

“Smith Dushkin, Dorothy (1903-1992), Composer, Music Teacher, and Diarist: American National Biography.” (1903-1992), Composer, Music Teacher, and Diarist | American National Biography, 16 June 2017, www.anb.org/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-1803852.

Smith Dushkin, Dorothy. Diaries from the author’s final semester at Smith College, January through September 1925, Box 18, Folder 1, Sophia Smith Collection of Women’s History, Smith College Special Collections.

Whitfield, Kay. “A Romance Set to Music.” Classic Chicago Magazine, 23 Aug. 2017, www.classicchicagomagazine.com/a-romance-set-to-music/.

Recent Comments