Weaving together archival documents and keen analysis, Sarah Mitrani’s investigation examines Smith students’ balance between traditional and modern femininity throughout World War 1. Mitrani inspects all facets of student life on campus, expertly detailing the changes Smithies faced from 1917-1919, from wardrobe to academic endeavors, religious life to community building. Beyond describing the Smith experience, Mitrani introduces a view into that era through artfully chosen primary photographs and publications, a clear testament to her comprehensive research. –Emma Geissinger Cutchins ‘24, editorial assistant

The 1917 Smithie: Caught in the Crossfire of a Changing World

Sarah Mitrani ’25

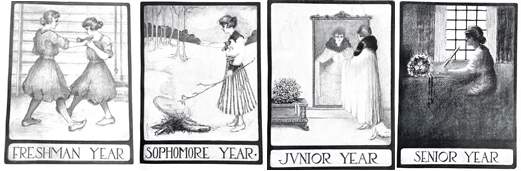

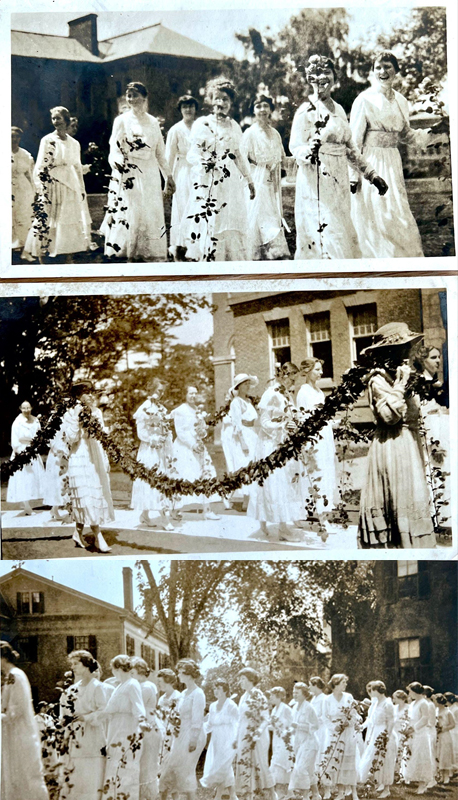

When the first American servicemen were called to duty in World War I in 1917, a different call was ringing in the ears of Smith students. Would they embrace traditional femininity and support their men and country from the background, or would they break the rigid boundaries of gender to embody power and influence openly? The unprecedented violence, death, and devastation of World War I permanently altered the lives of the soldiers and those directly caught in the war’s wake, and its impact extended beyond the battlefield. Deeply entrenched traditions, ideologies, and the status quo cracked under the pressure of rapid and drastic change, eroding the foundation on which America was built. Women’s roles in the home, the workforce, and American society adapted to fit the needs of a rapidly changing world, including the women of Smith College. Living in a time of global conflict and upheaval, the women at Smith College in 1917 may not have been in the trenches, but they were caught in the crossfire of two battling ideologies. As demonstrated through war-time student publications, student handbooks and yearbooks, along with records of Smith’s involvement in the war effort, many Smithies were pulled towards the past with its powerful traditions of femininity, sex-based hierarchies and roles, and rigid Christianity. But while some were drawn to the stability of the past, many Smithies pushed the boundaries of femininity towards a future where women were not relegated to the private sphere. Womanhood was changing, and the Smith students of 1917 were leading the charge.

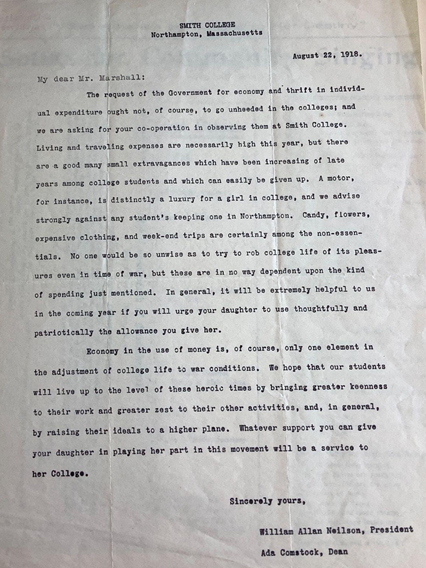

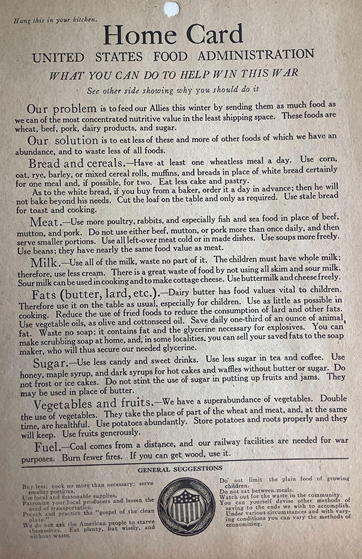

Swept up in the current of change and violence, traditional expressions of feminine patriotism, such as individual sacrifice and thrift, anchored Smithies in their roles as wartime women. Smithies made an effort to sacrifice excess and devote themselves to the service of others. The dissonance between the traditional values of womanhood and the new expectations of women brought on by the War, though, presented an internal conflict. President Neilson and Dean Comstock called on students and their families to refrain from indulging in luxury goods and unnecessary excess, encouraging them to express “economy and thrift in individual expenditure,” and limit “non-essentials,” such as “candy, flowers, expensive clothing, and week-end trips…” (Nielson). Women, primarily of upper and upper middle-class backgrounds, were told to shake off the selfish desire to consume excessively and instead to adopt feminine notions of personal restriction and sacrifice to support the nation. The December 5-11, 1917 issue of The Smith College Weekly proclaimed that the War had “transformed a nation of spenders into a nation of investors” and noted that the demands of the wartime economy required Smith students to “[forgo] all luxuries” such as designer clothing, sugar-filled candy, and beauty services (Smith College Weekly, December 5-11, 1917, p 1; 2).

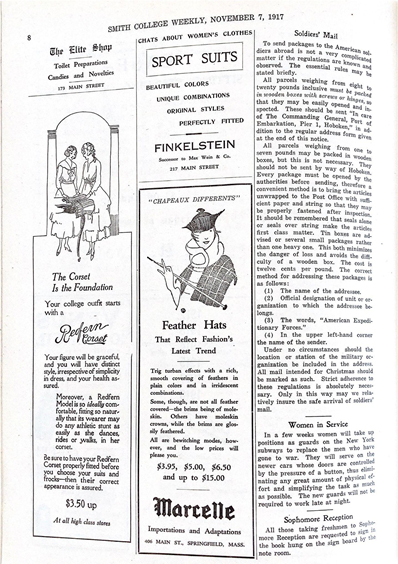

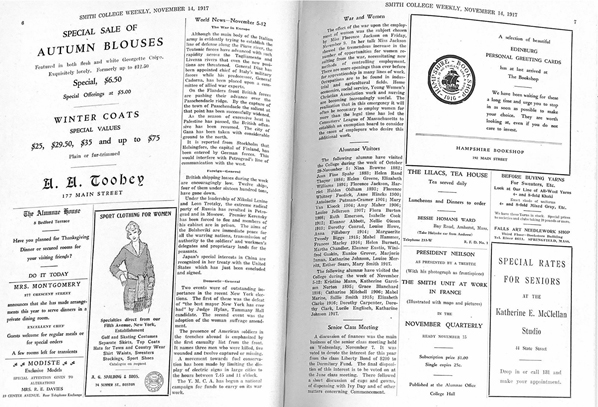

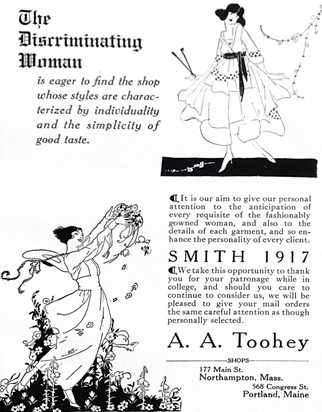

While Smith students’ spending power was called into action to save money or donate to the war effort, some Smithies embodied womanhood by shrouding themselves in expensive clothing, succumbing to the targeted advertisements for the lavish fashion trends in the back of the student 1916-17 and 1917-18 Class Books (1916-17 Smith College Class Book; 1917-18 Smith College Class Book). Plentiful posts in the Smith College Weekly suggesting that Smithies sacrifice expensive clothing and other non-essentials, alongside articles detailing the horrors of the war, were written in small print and hidden between large and eye-catching advertisements for clothing, candy, and non-essential services. “Feather hats that reflect the latest fashion trend” (Smith College Weekly, November 7, 1917, p 8), “Special Sale of Autumn Blouses,” and an enticingly-drawn young woman donning a pricey winter coat from New York, distract from the “first [American] casualty list from the front.” Similarly, they overpower the article about “women in service,” and eclipse the call to limit frivolous spending and consumption (Smith College Weekly, November 21, 1917, p 6). This dichotomy of affluent vs. charitable and service-oriented femininity is complex, as consumerism and femininity have always gone hand in hand, but femininity and service through sacrifice and thrift are also deeply connected. The societal conflict between the dominant and developing beliefs about women’s roles is encapsulated in these pages; one section reinforces the ideology that upper-class white women should concern themselves only with elitist and feminized activities, such as shopping for clothing and luxury goods, and another section supported the feminine expectation of women to aid their country through sacrifice and thrift.

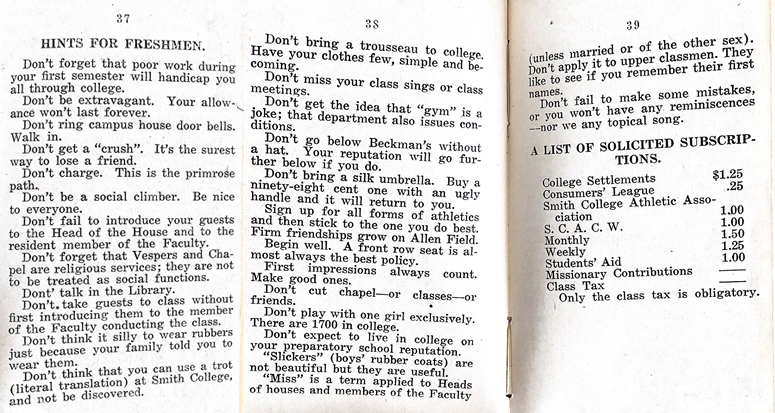

Traditional femininity was enforced and regulated from all directions, especially by Smith College. The 1917-18 Smith Handbook encourages Smithies to be “Just Right [by using] moderation in [their]choice of activities: not too much studying, not too much society or ‘fussing’ [“entertaining men”], not too much student activity, but enough to make a well-proportioned whole”(p 2). Smithies were told by the 1916-17 Student handbook, “Don’t be extravagant,” “Don’t be a social climber, be nice to everyone” (p 37), “Have your clothes few, simple and becoming,” and “Don’t go below Beckmann’s[1] without a hat. Your reputation will fall further below if you do” (p 38). Standards for behavior were clear and rigid, and Smithies were obligated to rise to these standards with feminine ease and grace. Women were still expected to be balanced, girlish, feminine, and perfect despite the earth-shattering violence and chaos echoing around the world. In an era defined by rapid and radical change, Smithies were challenged to adapt to expectations to be the patriotic self-sacrificing woman who surrenders her desires for the success of her country while being pressured to align themselves with traditional expectations to be dainty ladies primarily concerned with their looks and reputation.

Yet, just as traditional expectations of femininity were being reinforced, the traditional roles and occupations for women were shifting. World War I opened up new roles for women in the workforce, particularly educated and trained white women, as young men vacated their jobs to fight overseas. In this period, expectations of the upper middle-class white woman’s role in the social hierarchy moved towards direct involvement in the workforce and away from the subtle influence of the private sphere. On campus, Smithies took the initiative to support the Red Cross in making bandages and surgical dressings. In the 1917-18 school year, students worked one hour per week to make surgical dressings, totaling approximately 1,500 volunteer hours per week (Sampson, Smith College Archives). In classes and lectures, Smithies knit garments to donate to the war effort under the banner of the Smith College Relief Unit, donating over a thousand handmade garments by the end of 1917 (Student War Board, p 12-13). Later in the war, many students worked with recovering soldiers at the School of Psychiatric Work, now known as the School for Social Work (“Smith during World War I”). A mechanics class was introduced with the goal to train Smithies to be “ready to enter any automobile war-service open to women,” and to make “every girl her own chauffeur” (Young; Student War Board, p 20). Smith College encouraged students to apply for a fellowship for vocational training, stating that it supported women who stepped up to meet the world’s “urgent need of specially trained workers” in the male-dominated fields of “agriculture [and] secretaryship involving statistical training and scientific research” (Smith College Weekly, January 9, 1918, p 5). To aid the agricultural crisis spurred by the war and many men leaving their farms to fight and to help increase American food production, many Smithies joined the Women’s Land Army of America to volunteer as “farmerettes” (Spencer). They challenged stereotypes that women, particularly upper and middle-class urban white women, were too weak or unfit for physical labor. In a recruitment and donation pamphlet from The Women’s Land Army of America, the authors claim that farmers have been happily surprised by the hard work of the volunteer farmerettes, stating that “they made up for their comparative lack of physical strength by their greater quickness and conscientiousness,” and that their work was “equal to that of the men” (Women’s Land Army of America). Education historian Barbara Solomon writes in In The Company of Educated Women, that World War I “interrupted the segregated patterns of women’s employment at all levels [and] those who had experienced limitations as professionals gained renewed hope from the acceptance of all women in the crisis” (Solomon, p 139). Most educated wealthier and upper middle-class white women were trained for the feminized careers of teaching and social work, but World War I allowed women to redefine themselves and their role in the economy by working in other respected essential fields.

The internal conflict confronting the Smithies of 1917 was intensified by the contradictory expectations to fill men’s places in the workforce and the traditional expectation of women to either teach or become homemakers. What did being a wartime woman mean? What did being an educated woman in a changing world mean? Solomon writes that “at college, [women] accepted a double-edged message, to be useful and to be womanly,” causing them to wonder whether they “could meet both the traditional expectations inherent in being a woman and the new obligations introduced by her collegiate experience,” as well as the War (Solomon, p 115). The December 5-11, 1917 Smith College Weekly features an article about the significance of the War Work Council in helping Smithies gain skills and employment, aiming to make women “assets instead of liabilities” (Smith College Weekly, December 5-11, 1917, p 2). Education and vocational training made women useful in times of worldwide crisis, yet the conventional idea that an educated woman should remain in her home or a classroom persisted. Smithies in 1917 traversed a treacherous path where being too bold and directly involved might indicate that they were overstepping their positions, but working quietly in the background could leave them vulnerable to accusations that they weren’t sacrificing enough in the name of their country.

As many Smithies were stepping outside the boundaries of traditional white upper and middle-class expectations of women’s labor, they were also stepping away from the historically fundamental role of Christianity in women’s life and education. In the United States, religion, education, and womanhood had been inextricably linked, but World War I complicated the role of religion for many Smithies, both personally and within the Smith community. The War caused the importance and centrality of religion in a woman’s life to either intensify or wane. As an integral aspect of daily life, American society, and education, Christianity and Christian morality defined the boundaries of womanhood, and according to Solomon, the “ideal of the Christian wife, mother, and teacher gave repeated urgency to women’s education.” (Solomon, p 16). Benjamin Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and an early advocate for women’s education, asserted in Thoughts Upon Female Education, that the “female breast is the natural soil of Christianity,” and therefore women’s education should be valued as it fosters the spread and growth of Christianity by passing along her education to her children and husband (Rush, p 4). While Christianity was a foundation for much of women’s education, and it was their feminine duty to be moral guides for their children and communities, as the world changed, the role of religion in Smithies’ lives transformed.

The student publications of 1917 reveal that Smithies’ relationships with God and Christianity were less important than character development and morality. Religious ideas were not abandoned, but there was less of an institutional emphasis on Christianity. Although religion was a core value of Smith College, it was the 1916-17 Smith College Handbook that declared the school as now “non-sectarian in its management and instruction” (1916-17 Smith College Handbook, p 16). This is consistent with Solomon’s argument that “the practice of religion itself became a matter of private rather than institutional concern,” throughout the 20th century (Solomon, p 92). In the November 21, 1917 Smith College Weekly, a Smithie poignantly wrote that through war and the “process of education, our spiritual ideas are being changed. We no longer hold the concept of God as a crowned monarch, wise and powerful. Rather we have come to honor love and sacrifice” (Smith College Weekly, November 21, 1917, p 7). At the same time, however, many still turned to Christianity and God for strength and comfort. The Smith College Weekly on December 19, 1917, claimed that Smithies viewed the world “now less with the eyes of a child and more with the thought of a man,” and that the War “brings to [Smith] with added significance the realization of Christ’s message to the world, serving to emphasize our responsibility in living up to his teachings and seeking to carry them out” (Smith College Weekly, December 19, 1917, p 1). This shift in the importance and role of religion for Smithies and the Smith community in 1917 is emblematic of the larger metamorphosis women experienced in this era. Some Smithies fell back on traditional Christian values of femininity and the traditional role of sharing religious morality within the home, and some embraced the changing world by changing their personal relationship with religion, as well as shifting their expression of femininity and role in society.

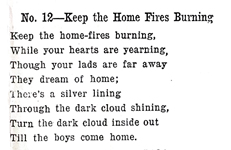

Against the backdrop of World War I, the Smithies in 1917 witnessed catastrophe, tragedy, and upheaval. They had to fight longstanding ideals of femininity and grapple with the internal conflict of whether to dismantle or reinforce traditional expectations of women. Some Smithies clutched tight to the traditional ideals of femininity when confronted with a changing world, and some jumped at the opportunity to subvert the restricting expectations of womanhood. Sung at Smith, the song “Keep the Home Fires Burning,” expresses the expectation of traditional femininity to stabilize the homefront while the men fought:

While some tended the fires at home, some Smithies grabbed the torch and led the charge towards a different future where women could define womanhood for themselves.

Works Cited

Lyrics of “Keep the Home Fires Burning” in Songs for Community Singing. War Service collection, College Archives, SSC-MS-00352, Box: 130, Folder: Activities on Campus. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Neilson, William Allen and Ada Comstock. Letter from President Neilson and Dean Comstock to Mr. Marshall. 22 August 1916. War Service collection, College Archives, SSC-MS-00352, Box: 130, Folder: Activities on Campus. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Photograph of Smith College’s Automotive Class. 1918. War Service collection, College Archives, SSC-MS-00352, Box: 130, Folder: Mechanics Unit. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Photograph of Volunteer Nurses’ Aids Smith Students Working at Dickinson Hospital. 1917. War Service collection, College Archives, SSC-MS-00352, Box: 130, Folder: Nurses’ Aides. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Photographs of 1917 Ivy Day. 1917. Classes of 1911-1920 records, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-01018, Box: 1896, Folder: Ivy Day 1917. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Photographs of Smith Students in the Women’s Land Army. 1918. War Service collection, College Archives, SSC-MS-00352, Box: 130, Folder: Women’s Land Unit – Photographs. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Photographs of Student Groups at Smith in 1917. 1917. Classes of 1911-1920 Records, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-01018, Box: 1896, Folder: Class of 1917 Groups. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Rich, rich701. 1917 Smith College Graduation 6 of 23. Uploaded 30 November 2014. Licensed under CC by 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/rich701/15918581635/in/album-72157649538008212/

Rich, rich701. 1917 Smith College Graduation 21 of 23. Uploaded 30 November 2014. Licensed under CC by 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/rich701/15296091754/in/album-72157649538008212/

Rich, rich701. 1917 Smith College Graduation, Student’s Building, 20 of 23. Uploaded 30 November 2014. Licensed under CC by 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/rich701/15732684487/in/album-72157649538008212/

Rush, Benjamin, and Samuel Magaw. Printed by Samuel Hall, Thoughts upon Female Education: Accommodated to the Present State of Society, Manners and Government, in the United States of America: Addressed to the Visitors of the Young Ladies’ Academy in Philadelphia, 28 July,n1787, at the Close of the Quarterly Examination, 1787.

Sampson, Myra M. War Work in Surgical Dressings, Report to President, 1917-18. 11 June 1917. War Service collection, College Archives, SSC-MS-00352, Box: 130, Folder: Surgical Dressings- Reports to President 1917-1918. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Smith College 1916-1917 Class Book. 1917. Student publications and student publications records, College Archives, CA-MS-01049. Smith College Archives, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Smith College 1917-1918 Class Book. 1918. Student publications and student publications records, College Archives, CA-MS-01049. Smith College Archives, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Smith College Student Handbook 1916-17. 1916. Student Religious Organizations records, Box: 3070, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00307. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Smith College Student Handbook 1917-18. 1917. Student Religious Organizations records, Box: 3070, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00307. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Smith College Weekly, December 5-11, 1917. 5-11 December 1917. Student publications and student publications records, College Archives, CA-MS-01049. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Smith College Weekly, January 9, 1918. 9 January 1918. Student publications and student publications records, College Archives, CA-MS-01049. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Smith College Weekly, November 7, 1917. 7 November 1917. Student publications and student publications records, College Archives, CA-MS-01049. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Smith College Weekly, November 19, 1917. 19 November 1917. Student publications and student publications records, College Archives, CA-MS-01049. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Smith College Weekly, November 21, 1917. 21 November 1917. Student publications and student publications records, College Archives, CA-MS-01049. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

“Smith during World War I.” Smithipedia, https://sites.smith.edu/blog/smithipedia/womens-war-work/smith-during-world-war-i/.

Solomon, Barbara M. In the Company of Educated Women: A History of Women and Higher Education in America. Yale University Press, 1985.

Spencer, Eleanor P. Letter From Eleanor Spencer to Margaret Grierson. 8 February 1943. War Service Collection, College Archives, SSC-MS-00352, Box: 130, Folder: Women’s Land Unit. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Student War Board. “War Activities At Smith” Pamphlet. June 1919. War Service Collection, College Archives, SSC-MS-00352, Box: 130, Folder: Student War Board (includes pamphlet “War Activities at Smith”). Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

The Woman’s Land Army of America. The Woman’s Land Army of America Pamphlet. 1918. War Service Collection, College Archives, SSC-MS-00352, Box: 130, Folder: Women’s Land Unit. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Young, Mary. “The Flying Ace And The Flying Horse,” published in The Valley Advocate. 24 June 1981. War Service collection, College Archives, SSC-MS-00352, Box: 130, Folder: Mechanics Unit. Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

[1] Beckmann’s was the candy and ice cream shop located at 127 Main street, now Broadside Bookshop (1917 Smith College Class Book, p 17).

Recent Comments