Eden Ball expertly navigates the nuance of sociocultural influence on the female orgasm. Ball examines the multipronged way by which social media, scientific bias, and social standards of sexual interaction impact a culture’s view of female pleasure. Ball links her own experience as a young woman participating in Western culture with larger trends and evidence regarding female sexual pleasure in order to paint a picture that is both global and personal. Rwandan sexual practices are contrasted with Western sexual traditions so as to break down stigmas preached by the latter and empower readers.” –Tatum McKenna ’24, editorial assistant

Female Orgasm in the U.S. vs. Rwanda: How Cultural Values Contribute to the Orgasm Gap

Eden Ball ’26

Introduction

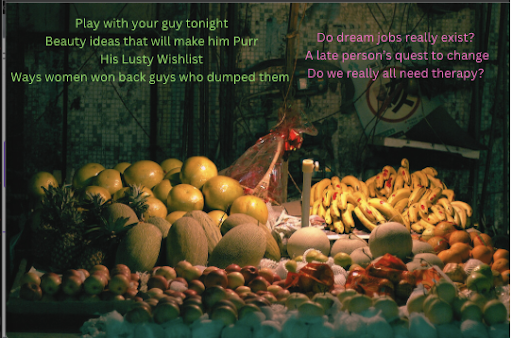

The quotes above, all sourced from Cosmopolitan magazine covers, may feel hauntingly familiar. It’s hard to navigate any grocery store without passing magazines like Cosmopolitan on your way to the checkout counter. The green section of quotes comes from magazines printed in the early 2000s and 2010s, while the orange group comes from the 2020s. The stark contrast in messages between the two groups is in many ways emblematic of the shift in societal messages regarding female sexual pleasure throughout the last two decades. For example, the green group of quotes emphasizes the woman pleasing the man, with no recognition of valuing her own pleasure. I grew up seeing Cosmopolitan magazines in familiar places, such as the ubiquitous checkout counter. Later, when I was in middle school and had questions about sex, Cosmopolitan articles were often one of the first search results to pop up on Google. These messages are widely accessible to youth.

After much reflection, I view these messages’ effects on me as a symbol of my unconscious inability to prioritize my pleasure throughout my heterosexual relationships. For this personal reason, I analyze the danger of promoting such messages in mainstream media, with the goal of precisely understanding how it leads both men and women to value women’s sexual pleasure less than men’s. More specifically, I examine the harmful effects of ingesting sexual media, the West’s perspective on the female orgasm, the social factors which impact women’s abilities to achieve sexual pleasure, and the physical ways in which sex is performed that cater to men’s pleasure over women’s. Finally, I focus on two Rwandan practices prioritizing female sexual pleasure, Gukuna and Kunyaza, to demonstrate the stark contrast between a culture that prioritizes female sexual pleasure and the American sexual culture, which conversely creates a taboo around it. I hope the results of this analysis give my readers a greater sense of agency regarding their and their partner’s sexual pleasure.

As a caveat, in this paper, the terms “woman” and “female” refer to a person assigned female at birth who identifies as a woman. I must emphasize this distinction; some people have the sexual and reproductive anatomy of the female sex but do not identify as women, and vice versa.

Sexual Media Consumption

How are our perceptions of sex and sexual pleasure formed? Sexual media, like pornography, is accessible and popular. Furthermore, it can have a dangerous effect on how we view gender and sexual pleasure. One alarming message that mainstream porn carries is that aggression during sexual activity is the norm. For example, in a 2005 study titled “Aggression and Sexual Behavior in Best-Selling Pornography Videos,” one of the main takeaways was that the perpetrators of sexual violence in sexual media are overwhelmingly men, and the victims of such treatment are overwhelmingly women (Bridges). From the same study, researchers report that their “findings indicate high levels of aggression in pornography in both verbal and physical forms. Of the 304 scenes analyzed, 88.2% contained physical aggression, principally spanking, gagging, and slapping, while 48.7% of scenes contained verbal aggression, primarily name-calling” (Bridges). The sheer prevalence of aggressive behavior in pornography sends a signal to viewers that this is normal in the bedroom, perhaps even preferred. Furthermore, this perception is bolstered by the reaction of the recipient of the aggressive behavior. According to the study, women’s reactions were portrayed as either neutral or, more commonly, as enjoying such treatment (Bridges). This portrayal of enjoyment perpetuates the normalization of mistreating women to please men, as well as the idea that women should experience satisfaction from such aggressive treatment. This messaging is found in other forms of media besides porn, as exemplified in the quotes from the magazines above.

To further investigate the themes being perpetuated in sexual media, I decided to see what kinds of messages I would be subjected to via Pornhub, the world’s most-used website for pornography (Hillinger). Clicking on Pornhub’s website, I was immediately spammed with video clips of genitalia. Within just two or three scrolls of the mouse, I was met with titles of videos such as:

- “Bratty teen step daughter gets it”

- “Busty little step daughter Sadie Pop teases stepdad and makes him fuck her tight twat”

- “Sexy teen Latina”

- “Riding Daddy”

- “Slutty stepsister”

These are a few of the more ‘tame’ titles that floated across my screen, yet they are simultaneously shocking and disturbing. With these titles come the themes of infantilizing women and fetishizing the rape of minors. Even a cursory search on Pornhub reveals multiple disturbing messages within sexual media and pop culture, all of which viewers are ingesting. Considering these examples, we should wonder about the demonstrable impact of this messaging. In an article published in the International Journal of Social and Economic Sciences, researcher Giray Saynur Derman explains how social perception management, which consists of strategies for managing how people perceive the reality of society, is a new concept. More specifically, the US Department of Defense only officialized this concept in the 20th century, as the risks that media messaging imposed became more alarming. Derman explains these risks when stating that “. . . perceptions can be easily manipulated, mass movements can be created, and social events can be easily manipulated” (Derman). This lends credence to the idea that the media we consume possess considerable power and influence, which explains how the perpetuation of violence against women in sexual media spreads the values of violence against women in non-scripted sexual encounters and daily life (Yang).

Media consumption is just one piece of the complex and overwhelming puzzle that dictates the ability of women to experience sexual pleasure in the Western world. This context is important, as the objectification of women leads to their lack of feeling entitled to experiencing sexual pleasure and, thus, they experience fewer orgasms (Mahar). In order to bridge the orgasm gap between men and women, it is necessary to examine the issue from all angles, such as the danger of relying on sexual media for sexual pleasure and expectations. An additional angle is understanding what the female orgasm is from a scientific perspective.

Definition of Orgasm

There are multiple definitions of the female orgasm within the scientific community. First, it is essential to recognize that not only can a woman experience different types of orgasms, but every woman’s body and sexual responses are different. James G. Pfaus, a well-known researcher on the intersection of sexual, neural, and biological behavior, explains three types of female orgasms commonly exhibited among women: a “wave,” which consists of short bursts of pelvic contractions preceded by a rhythmic movement of pelvic floor tension and release; a “volcano,” which consists of increasing pelvic floor tensions that build to an orgasm; and an “avalanche,” which consists of higher pelvic floor contractions, but a downward contraction of pelvic floor tension during and after orgasm (Pfaus, “Women’s Orgasms”). Additionally, women’s orgasms vary based on the stimulation of distinct body parts; the female body features multiple erogenous and sensitive regions, the most common being the clitoris and particular areas inside the vagina, such as the G-spot and cervix (Pfaus, “The Whole”).

This research provides a scientifically accurate definition of what constitutes a female orgasm, which I find necessary to include since American pop culture bombards society with depictions of female orgasms that are simply unattainable (Niineste). These misrepresentations can make women feel pressure to perform sex in a specific way. On the other hand, suppose a woman cannot function in these ways: in that case, this can lessen a woman’s view of her self-worth and allow America’s patriarchal society to justify labeling her as a sexual “failure.”

The Female Orgasm as Natural

Multiple cultures have supported the female orgasm throughout history, a contrast which highlights the irrationality of the American stigmatization of the female orgasm. For instance, in ancient Greek mythology, Zeus believed that women experience greater pleasure than men from sex (Pfaus, “The Whole”). Rwanda, in particular, has a rich history of supporting female sexual pleasure. More specifically, according to a narrative passed down among generations, during the third dynasty of the Rwandan monarchy, the queen’s husband went off to fight in a war. Alone, the queen grew sexually unsatisfied; she instructed one of her guards to have sex with her. Because he was nervous, the guard began to tremble. Instead of penetrating the queen, his penis shook against her clitoris and labia. This sensation drove the queen to ejaculate. This is how the practice which helps women achieve Kunyaza—known in the West as “squirting”—was born in Rwanda (McCool).

Additionally, versions of this narrative explain that the liquid from the queen’s ejaculation created the Great Lakes, a region that Rwanda occupies (Akande). In a way, Kunyaza is inseparable from Rwandan history, as the Great Lakes are visible and permanent to the landscape of Rwanda. This demonstrates the national importance Kunyaza holds, which shocks me as an American who never learned about female ejaculation in her sexual education at school. This leads me to wonder how my view on female pleasure, in general, would have been more positive had female sexual practices such as ejaculation been celebrated instead of ridiculed during my youth. Additionally, the Rwandan tradition of Gukuna, which in English roughly translates to “labia pulling,” involves stretching the labia skin to elongate this part of the body for the purpose of increasing female sexual pleasure. This practice is also prehistoric, as anthropologists have found depictions of elongated labia in cave paintings (King). Thus, it is evident that prioritizing female sexual pleasure is not generally unnatural, as many cultures held practices and beliefs which prioritized this pleasure before the influence of Western Christianity and colonialism.

Western Culture’s Historical Perspectives on Female Orgasm

Western cultural views on sex and, more specifically, female sexual pleasure have changed in multiple ways. These cultural changes have led to the dramatic orgasm gap in the West. For example, for thousands of years, the clitoris was considered equal to the penis, but physicians such as Galen, in the 2nd Century, and Vesalius, in the 16th Century, decided that the vagina, not the clitoris, was the equivalent of the penis (Pfaus, “The Whole”). It is not coincidental that clitoral stimulation often does not lead to such direct pleasure for men as penetrative sex does and that men changed the narrative to support penetrative sex as the ultimate way of achieving sexual pleasure for females. America’s patriarchy has capitalized on the incorrect medical beliefs explained above, embedding these beliefs into America’s sexual culture.

Furthermore, in the early 1900s, psychologist Freud introduced the psychosexual stages of development, in which he declared that ‘mature’ orgasms were derived exclusively from vaginal stimulation (Freud, as qtd. in Pfaus, “The Whole”). This angers me because while Freud can be held in high regard by some, this idea–which is exceptionally damaging in terms of the effects on women’s sexual pleasure–was heavily circulated and thus became popularized. Additionally, when I was in high school, I learned about Freud’s psychosexual stages of development in two classes, and in neither of these classes was this issue raised, nor was Freud critiqued. This exemplifies how embedded these sexually stigmatizing ideas are and how difficult it is for people to acknowledge them without conscious attention. There was a sociocultural shift in the 1960s and 70s when the clitoris became a sociopolitical flag-bearer. Many feminist scholars, such as Anne Koedt and Andrea Dworkin, condemned Freud’s premise of the vaginal orgasm. Dworkin related the entrance of the penis into the vaginal canal to the man forcing himself into a woman, splitting her apart (Dworkin, as qtd. in Pfaus, “The Whole”). The wording and imagery create the connotation that every time a penis penetrates the vaginal canal, this is inherently “unwanted” by the female’s body.

While I admire the values of feminists in general, I struggle to support Dworkin’s notion due to its biological inaccuracy; the vaginal canal expands to fit a penis during sexual intercourse and to accommodate childbirth. This context explains why there are different views on the ‘controversy’ of female ejaculation in America; some fetishize these women, while others shame them, labeling them as too erotic (Rodriguez). This type of shaming also occurs in Rwanda. For example, there is a derogatory Rwandan term, mukagatare, which means “rock woman” and is used to define women who are unable to ejaculate during orgasm (McCool). Both examples demonstrate the patriarchal culture’s way of assigning moral meaning to a bodily process. While I find it empowering that Rwandan women are encouraged to ejaculate, I also recognize the common theme between Rwandan and American sexual cultures of shaming women due to their sexual performance.

The Impact of Societal Factors

While all of the aforementioned points are critical for understanding the orgasm gap, there are also two more additional factors to consider. One of the two factors stems from sociocultural norms, as research indicates that one’s headspace dramatically affects one’s ability to experience pleasure. The difference in how Rwandans and Americans view female sexual satisfaction explains the apparent differences between each culture’s acceptance and promotion of female sexual pleasure. Social standards of sexual modesty lead to a process through which participants value their sexual experiences based on cultural representation. To explain this further, statistically speaking, women experience higher orgasm rates with clitoral stimulation than with vaginal stimulation (Niineste). Yet, clitoral stimulation is often performed as an act separate from intercourse. Thus, if the patriarchy prioritizes men’s sexual pleasure, this inherently signifies that clitoral stimulation will be valued less than penetrative sex. While this information is not surprising, it is hugely concerning, as the relationship between social inequalities and the bedroom suggests that women cannot gain rights in the bedroom if they do not gain equal rights elsewhere. And, while both sexes are concerned with whether or not they can please their partners, the culmination of which is usually thought of as the orgasm, this concern does not result in equal orgasm rates among the sexes.

Additionally, women have also been found to be more vulnerable to various other types of cognitive distractions than their male counterparts, particularly concerning the spatial surroundings of sexual activity, for example the absence or presence of light and the acoustic properties of the room (Niineste). Thus, women not only have the added pressure of societal expectations, they additionally have the tendency to be more greatly affected by these external pressures. Such external pressures can be thought of as a mental “noise,” distracting one from being able to experience sexual pleasure in their fullest capacity.

Gukuna can be a collaborative practice, with young women helping each other learn the technique (“Inside Rwanda’s Labia Stretching Ritual”). I view this as a demonstration of the lack of stigmatization of the female body, particularly the female genitals. To me, the ability to have one’s body be accepted by their community to the extent that other women can be supportive of the openness around such bodily changes is incredibly empowering. This helps to explain why women in Rwanda may feel more secure in their sexual pleasure, as their genitals hold less of a taboo.

The Impact of Physical Factors

The second factor contributing to the orgasm gap relates to the physical performance of sex. The culturally ubiquitous form of penile-vaginal intercourse conflicts with the fact that for a substantial proportion of women, direct clitoral stimulation is needed for orgasm. While penile-vaginal sex is the “most reliable route” for male orgasm, only a tiny percentage of women report consistent orgasm through intercourse (Niineste). This social norm is evidence of the sociocultural changes discussed above. The lack of value ascribed to clitoral stimulation, despite the scientific evidence that it leads to higher rates of female pleasure, indicates an issue in societal values. The information discussed above differs dramatically from the Rwandan practice of Kunyaza. In this practice, while inner penetrative vaginal stimulation is sometimes performed, it is distinct from what is often described as vaginal sex in America. In Kunyaza, the man strikes the glans of the clitoris with the glans of his erect penis. The man moves in the same motion from top to bottom and vice versa, or from left to right and vice versa, before making circular movements. In Kunyaza, if vaginal penetration occurs, the penis is typically moved from side to side of the vaginal canal or in circular motions. This inner stimulation is followed by further stimulation of the vulva (Ijewere). Thus, the practice focuses on women’s pleasure.

Additionally, while the man receives stimulation during traditional intercourse, the stimulation level is subpar compared to the stimulation the woman receives during Kunyaza. In some instances, the woman is given control over the man’s penis, which is not only a physical marker of the woman’s power over the man’s body but also a philosophical one, as it symbolizes the man relinquishing his power to the woman, and allowing her to wield it. Furthermore, Kunyaza is performed before conventional penetrative vaginal sex has occurred, as the penis becomes erect during this practice. This establishes the precedent of prioritizing the woman’s pleasure.

Furthermore, Gukuna as a practice dictates how biological sex is performed. Not only does stretching the labia skin create more surface area to be pleasured, but it also makes the elongated skin more sensitive. Gukuna stands out to me due to its dramatic distinction from the American porn industry’s beauty standard of minimal or almost non-existent labia. For example, in high school, I remember multiple times when my friends would comment on the embarrassment they felt concerning the visibility of their labia. In particular, they used “outie” to describe their “long” labia, often followed by remarks about their embarrassment over having their sexual partners see this part of their bodies. Gukuna can also be viewed symbolically; as the labia lengthen, the female sexual organs take up more space. To me, this is quite empowering.

It is worth noting that Gukuna has been critiqued due to the irreversibility of these physical changes, and the fact that it occurs among minors (Devlin). These girls permanently alter their bodies at a young age due to the influence of others in their community. This raises concern among western advocates of the issue of consent. While I identify as a western feminist, I find it necessary to view the issue of consent by recognizing that it is a very western term regarding body autonomy. Furthermore, I must practice cultural relativism, acknowledging that these cultures differ, without comparing Rwandan culture to American culture and labeling the latter as the inherently standard example.

Conclusion

Above, I discuss the multiple definitions of the female orgasm, examples of female orgasm throughout history, how American culture has changed regarding its views on female sexual pleasure, how this cultural change has led to the orgasm gap in America, and the research regarding the mental and emotional barriers that lead to the orgasm gap.

As a young woman raised in America, I feel the effects of living in a culture that prioritizes male sexual pleasure over my own. However, I also feel incredibly empowered after learning to prioritize my sexual pleasure and recognize dangerous messages in the media. I hope this paper allows those who identify as women and who feel the effects of the western stigmatization of female sexuality to gain confidence in themselves and to normalize their body’s natural sexual processes.

Works Cited

Akande, Habeeb. “African Technique for Female Ejaculation.” Rabaah Publishers: Independent UK Publisher, https://rabaah.com/african-technique-for-female-ejaculation.html. Accessed 20 Oct. 2022.

Bridges, Ana J., et al. “Aggression and Sexual Behavior in Best-Selling Pornography Videos: A Content Analysis Update.” Violence Against Women, vol. 16, no. 10, 2010, pp. 1065–1085, . Accessed 10 Apr. 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/47566223_Aggression_and_Sexual_Behavior_in_Best-Selling_Pornography_Videos_A_Content_Analysis_Update

Cover image. Cosmopolitan. June-July, 2022.

Cover image. Cosmopolitan. July, 2022.

Cover image. Cosmopolitan. Aug.-Sept., 2022.

Cover image. Cosmopolitan. Dec., 2022.

Derman, Giray Saynur. “Perception Management in the Media.” International Journal of Social and Economics Sciences, vol. 11, no. 1, 2021, https://ijses.org/index.php/ijses/article/view/301. Accessed 10 April. 2023.

Devlin, Kayleen, and Lily Freestone. “Rwanda: Sexual Pleasure and Controversy – BBC World Service.” YouTube, uploaded by BBC World Service, 22 May 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xkzhC4FfHjE. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Ijewere, Esther. “Kunyaza: The Sensual Rwandan Tradition Which Guarantees Explosive Female Orgasms.” Women of Rubies, 24 Nov. 2019, https://womenofrubies.com/kunyaza-the-sensual-rwandan-tradition-which-guarantees-explosive-female-orgasms/. Accessed 20 Oct. 2022.

Hillinger, Suzanne. (2023). Money Shot: The Pornhub Story [Film]. Jigsaw Productions, 2023, https://www.netflix.com/title/81406118. Accessed 12 Apr. 2023.

“Inside Rwanda’s Labia Stretching Ritual – Gukuna.” YouTube, uploaded by the DW the 77 Percent, 1 Dec. 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kHFNG0l2CPI. Accessed 3 Dec. 2022.

King, Cameron. “A To Z of Sexual History: Gukuna Imishino (Means ‘I Love Long Labia’).” Vice, 13 Jan. 2010, https://www.vice.com/en/article/qbam43/the-a-to-z-of-sexual-history-g-gukuna-imishino-some-people-are-obsesed-with-labias. Accessed 2 Dec. 2022.

Mahar, Elizabeth A., et al. “Orgasm equality: Scientific findings and societal implications.” Current Sexual Health Reports, vol. 12, no. 1, 2020, pp. 24–32, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-020-00237-9. Accessed 2 Dec. 2022.

McCool, Alice. “The Joy of Kunyaza: Women’s Plesure Comes First in Rwanda.” New Internationalist, 16 Dec. 201, https://newint.org/features/web-exclusive/2017/12/15/kunyaza-rwanda-sex-equality. Accessed 2 Dec. 2022.

Niineste, Rita. “The Sexual Body as a Meaningful Home: Making Sense of Sexual Concordance.” Open Philosophy, vol. 4, no. 1, 2021, pp.269-283, https://philpapers.org/rec/NIITSB. Accessed 2 Dec. 2022.

Pelden, Sonam, et al. “Ladies, Gentlemen and Guys: The Gender Politics of Politeness.” Social Sciences, vol. 8, no. 2, 15 Feb. 2019, p. 56, https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8020056. Accessed 1 Dec. 2022.

Pfaus, J, et al. “Women’s Orgasms Determined by Autodetection of Pelvic Floor Muscle Contractions Using the Lioness ‘Smart’ Vibrator.” The Journal of Sexual Medicine, vol. 19, issue supplement 3, 1 Aug. 2022, pp. S2-S3, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2022.05.011. Accessed 2 Dec. 2022.

Pfaus, James G., et al. “The Whole Versus the Sum of Some of the Parts: Toward Resolving the Apparent Controversy of Clitoral versus Vaginal Orgasms.” Socioaffective Neuroscience & Psychology, vol. 6, no. 1, 25 Oct. 2016, https://doi.org/10.3402/snp.v6.32578. Accessed 2 Dec. 2022.

Rodriguez, Felix D et al. “Female ejaculation: An update on anatomy, history, and controversies.” Clinical Anatomy, vol. 34, no. 1, Jan 2021, p. 103-107, DOI: 10.1002/ca.23654. Accessed 2 Dec. 2022.

Wallen, Kim, and Elisabeth A Lloyd. “Female sexual arousal: genital anatomy and orgasm in intercourse.” Hormones and Behavior, vol. 59, no. 5, May 2011, p. 780-92, doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.12.004. Accessed 2 Dec. 2022.

Yang, Dong-ouk and Gahyun Youn. “Effects of Exposure to Pornography on Male Aggressive Behavioral Tendencies.” The Open Psychology Journal, vol. 5, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1–10, https://doi.org/10.2174/1874350101205010001. Accessed 10 Apr 2023.

One thought to “Female Orgasm in the U.S. vs. Rwanda: How Cultural Values Contribute to the Orgasm Gap”

I loved this essay, Eden!! Fascinating work 🙂