Aurezuh Sikes expertly articulates the parallels between the zealous practices of drag and traditional religion. This work is a beautiful representation of the intimate exercises that bind our Smith community together, and through Sikes’ work, we are able to examine and appreciate the differences and, more importantly, the similarities we have with one another. Sikes keenly considers the modern evolution of spirituality and how the desire for closeness with each other persists and changes with context, such as in our “concentric queer circles” (as Sikes accurately puts it). Ultimately, we as readers are asked to inspect how our rituals are not just fun nights out, but also long-standing embodiments of “meaningful connection.” –Julian Hernandez ’24, editorial assistant

Drag as Corporeal Spirituality at Smith College

Aurezuh Sikes ’26

Within the concentric queer circles of Smith College, religion is varied, volatile, and often difficult. We are just on the edge of grown-up; some of us are working through the religious trauma of our childhoods, while others use their religion to lay the groundwork for their activism. There are many students who would not consider themselves religious but are happy to give a detailed reading of one’s astrological birth chart or tarot cards. Though our spiritualities are disparate, we are not without common practice. We go to drag shows to worship.

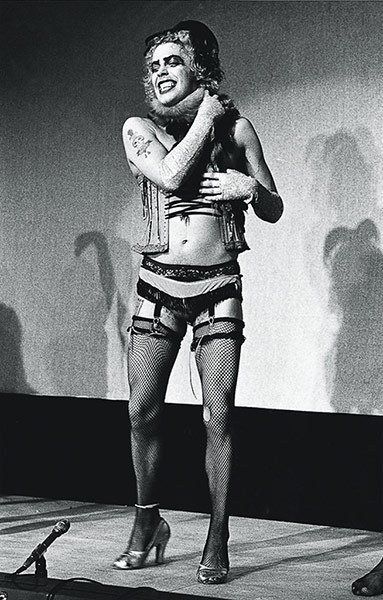

At this historically women’s college it’s hard to find a show that doesn’t include drag. Kings and queens abound in student theater productions, Rocky Horror Picture Show shadowcasts, drag nights, and drag bingo. These are our rituals of community and of affirmation.

Recently I attended my first service at a congregational church. I was surprised to find it structurally similar to a performance of Rocky Horror. Thematically, Palm Sunday was nothing like this campy cult classic, and much more subdued. However, the repeated performance of a meaningful text, call-and-response audience participation, prevalence of music, and special dress reserved for the occasion are clear parallels. The atmosphere of a shadowcast summons a religious depth of feeling, but do we perform Rocky Horror to feel closer to a god? No, not God in the monotheistic sense. We put on these shadowcasts multiple times a year because people need ritual. The costumes, singing, dancing, and yelling are what make the spirituality of such performances material. Drag and adjacent performances are ways of corporealizing our beliefs and values as a community and an expression of material spirituality.

According to professor of Catholic studies and history Robert Orsi, one of the functions of religion is “making the invisible visible” and “concretizing the order of the universe” (73). He argues that it is necessary for the continuation of religious belief and practice that practitioners experience religion in their bodies. Through sensation, muscle memory, and costume, religion is corporealized (Orsi, 74-5). Orsi expands upon the way religion is materialized–as in made physically tangible–by mid-twentieth-century Catholics and specifically the way children are encouraged to embody spirituality in the Catholic church. He finds that children are the ultimate symbol of continuity because they represent the hopes of the current adult generation and will form the next. As such, there is a focus on traditions that make religion undeniable and present for children (75). These include dress-up play as clergy, constant prayer, and highly enforced specific physical comportment at mass (85, 99-100). The sensory experiences of church are also incredibly impactful for children, as Orsi notes that “some vomited at the first whiff of incense” (94). These associations follow people into adulthood, informing their personal experiences for the rest of their lives. A memorized prayer could become an unconscious comfort, and the memory of being reprimanded in church might stay with someone their entire life (88, 108). Corporealized religion has impactful, lasting physical effects; but is this seen only within institutionalized religion? Can material spirituality exist outside of belief altogether?

Since the 1990s, there has been a trend in American demographics of declining religious affiliation (Drescher, 5). This has been accompanied by the increasing prevalence of a group often described as “spiritual but not religious” (or SBNR) (4). The defining trait of this group is that each person’s spiritual experience can be so individualized that they are incomparable in all ways except for their resistance to institution. Elizabeth Drescher tries to draw more similarities among SBNR people in her book Choosing Our Religion. She ends up expanding this category even further to search for similarities between all religiously unaffiliated Americans, who she terms “nones” (2). Popular stereotypes about SBNR folks hold that their spirituality lacks cultural context and perpetuates neoliberal individualism. In “Consuming Spirituality,” Melissa Wilcox describes the spirituality at the intersection of these stereotypes as “bricolage” wherein practitioners collect “specific beliefs and practices, often in separation from their broader traditions and divorced from their cultural and historical contexts” (138). This often involves the appropriation of practices from marginalized traditions. According to Wilcox, “bricoleurs are seasoned shoppers in the neoliberal spiritual marketplace,” which they participate in by assembling a grab-bag of practices from various traditions (139). The trappings of consumerism which go along with this are often the way this wide range of spiritual beliefs become material for the SBNR.

That said, there are those whose spirituality is not an individualist self-improvement project but an avenue to community organizing. For some queer activists, a bricolage spirituality can be a tool box from which to draw in situations where no religious institution can offer a sufficient solution. Wilcox complicates her argument by recognizing that in the case of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, an activist order of queer nuns, “the spirituality that they practice is also in some way a spirituality of justice” (140). Given that those nuns which she spoke with fit the description of spiritual bricoleur, and are thus complicit in the neoliberal commodification of spirituality, how can their spiritualities still be just?

In belonging to a community that explores spiritual practice toward a common cause, the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence combat the individualism that SBNR identity implies. In seeking community, they have fulfilled the social function of religion without limiting themselves to an established religious institution. The community is that of a volunteer organization which materializes itself through performance and action. The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence perform their activism in drag: their drag identities and spiritualities are intrinsically interwoven. They work to weave strong communities that become less susceptible to neoliberal individualism as their capacity for meaningful connection and mutual support grows.

I would not argue that this spiritual involvement is the case for all drag performers, SBNR or otherwise, but it is clear that drag performance is an important ritual within queer communities. It is a symbol that reinforces connection while destabilizing gender, an action central to queer identity. This is especially true at Smith, where community and spirituality are intertwined in all the rituals of college life. Rocky Horror shadowcasts are notoriously nights which coincide with climatic changes in how people interact, and often serve to bring them closer to each other. These explorations of identity through performance make our community material, and this community’s chosen rituals are, in their symbolism and fantasy, spiritual. Through Rocky Horror, we reproduce a spirituality that embodies queerness in a strike against the palatability of neoliberalism. We reaffirm the families we have created for ourselves.

Works Cited

Drescher, Elizabeth. Introduction. Choosing Our Religion: The Spiritual Lives of America’s Nones, by Drescher, Oxford UP, 2016, pp. 1-15.

Orsi, Robert A. “Material Children.” Between Heaven and Earth: The Religious Worlds People Make and the Scholars Who Study Them, by Orsi, Princeton UP, 2013, pp. 73-109.

Wilcox, Melissa M. “Consuming Spirituality: SBNR and Neoliberal Logic in Queer Communities.” Being Spiritual But Not Religious: Past, Present, Future(s), edited by William B. Parsons, Routledge, 2018, pp. 128-145.

Recent Comments