In this powerful essay, Rheva Wolf critically exposes the ways by which botanic gardens perpetuate legacies of colonialism, extraction, and erasure. They then propose the path botanic gardens should take to decolonize, for instance by involving Indigenous populations in the cultivation of plants. Ultimately, Wolf urges botanic gardens to be agents of positive social change in order to exist and grow in this rapidly changing society.–Kinjal Potdar ‘26

Decolonizing Botanic Gardens: How We Move Toward an Equitable Future

Rheva Wolf ’28

Public and private gardens have already adapted to a changing society and evolving scientific goals, serving as pre-monastic grounds, systematic gardens, research facilities, and modern tourist destinations. Yet botanic gardens, perhaps surprisingly, have centuries-long legacies of colonialism, extraction, and erasure. The movement to reevaluate and redesign botanic gardens is part of a larger wave of rethinking museums and collections, exploring the deeper impacts of what it means to collect. Recognizing that museums and collections, such as the collection of a botanic garden, can be agents of social change allows botanic gardens to be more than beautiful venues or locations for biological research, but to begin to bridge divides in–or decolonize–knowledge and access. Decolonization is a buzzword across social media platforms, news cycles, and political conversations, but what does it truly mean to decolonize something? A commonly misunderstood yet vital aspect of decolonization is action. Surely, we must decolonize our thinking, read more Black and Indigenous writing, and expand our knowledge, but to really unpack hundreds of years of legacy, we must take action. Decolonization calls for settlers to cast away their “settler innocence” and take up the responsibility to deconstruct systems that continue to oppress Black, Brown, and Indigenous people and move toward a more socio-ecologically equitable future. With careful planning and deliberate execution, gardens can decolonize by recognizing the changes that need to happen, establishing goals, and creating a guide to ensure the right priorities are in place.

Decolonizing botanical gardens begins with understanding how the garden stems from colonial pasts and why it therefore must be decolonized. First, we must recognize botanic gardens as collections of plants obtained through colonial extraction (Neves 265). A prime example of deep-rooted colonial extraction is present in the Latin names of collected plants. When a botanic garden extracts a plant, the garden gives it a Latin name and erases its native name. As Neves asserts, by replacing the local name, you also erase the world and history of that plant and appropriate the plants of Indigenous people into a naming system built to pay tribute to male European explorers, politicians, and slave owners (266).

Secondly, we must understand the past power hierarchies between formerly colonized parties and their colonizers present in collections. Many botanic gardens were constructed to serve colonial interests such as plant acclimatization and economic profit from lucrative crops, meaning their very foundations were built on colonial power. A colonizing nation would take a plant or cash crop known to be lucrative, remove it from its habitat, and bring it to their new imperial territory where they would cultivate it for immense profit, making the botanic garden a tool of colonization: for example, Great Britain’s spice trade via the East India Company (Blais). Even today, the imbalance between colonizers and those colonized persists. Often, when botanic gardens contact Indigenous elders for their knowledge or resources on a research project, the elders never hear back and do not receive the publications they assisted in creating (Cuerrier 2). This imbalance leaves the colonizers as the sole bearers of the knowledge and further ensures what is known as the “settler future” by creating knowledge that is exclusively held by the colonial settler classes for their benefit (Hassouna). These persistent colonial power structures and implicit hierarchies are what many modern botanic gardens are seeking to unpack.

As Robert Janes asserts in his book Active Collections, social and environmental issues are deeply intertwined, and we must consider both together as we simultaneously develop a “relationship with the natural world and with each other” (91). Collections such as museums and gardens present us with the opportunity to tackle these problems by connecting with social ecology and our ecological selves as we discover these connections. While we know that museums and gardens can’t solve climate change or other massive global crises, they can continue to build a new place for themselves that enriches the opportunities and lives of their communities and patrons as they realize problems, identify their solutions, and rebuild their structures (Janes 93). So even though it may seem far-fetched to tackle social issues of colonization in a place like a botanic garden, restructuring through a lens of ecological and social equity will allow these spaces to recontextualize their place in our modern society. This new and valuable perspective allows botanic gardens to grow a social role as they decolonize and begin to make a real impact.

So, if we can recognize the history of botanical gardens, identify the problems that still exist today, and have the resources to implement change, where do we start? What does it mean to decolonize a garden? A garden cannot be decolonized in one action; rather, it takes careful research, planning, communication, and collaboration. One such example was initiated by the Montreal Botanic Garden in 2019, in a project funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, to explore native medicinal plants in the Québec Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee (Cuerrier 2). The garden partnered with the local Cree Nation to delve into research on treating diabetes with botanical medicines. To work toward bridging the knowledge gap, Alain Cuerrier and his team held weekly meetings in the communities they were working with, translated important information across multiple native languages, and worked diligently to ensure accessibility and balanced power dynamics between the Indigenous and historically settler populations. At the completion of the project, Cuerrier’s team hosted workshops and published a book on Cree anti-diabetic medicinal treatment in many local languages. Indigenous communities involved are carefully credited in this publication, an important and often forgotten addition. By both collaborating with and repeatedly intentionally acknowledging the work and knowledge of the Cree people, the Montreal Botanic Garden was able to successfully partner with the local Inuit community in a historically unprecedented way for botanic gardens.

Cuerrier’s project goes beyond its inherent reach of the communities they worked with to also lay a foundation for many more projects like this to come at the Montreal Botanic Garden and elsewhere across the globe. Following the project’s successes, we can outline best practices and methods of communication and collaboration. The work not only strengthens their community connections but also informs their ongoing choices in collection maintenance and structure toward decolonization based on what they can learn from the communities they work with. Perhaps the Montreal Botanic Garden will begin to cultivate mutually beneficial plants in its collections, or maybe the garden will recognize the value of cross-lingual information and translate its collection guides and tags into more languages accessible to Indigenous populations. Decolonizing a garden is not a simple task, but each step sets itself up for the next, slowly forging a path forward.

Another important facet of botanic garden decolonization is cultivation and collaboration that does its best to exclusively benefit Indigenous or historically oppressed populations in order to begin to balance out decades of cultivation that exclusively benefitted settler populations. This collaboration is beginning to be put into action by the Smith College Botanic Garden in Northampton, Massachusetts under director John Berryhill. Berryhill has partnered both with the staff of nearby living gene banks and with the Hassanamisco Band of the Nipmuc Nation to cultivate collections of sweetgrass (Anthoxanthum nitens) and Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides), culturally important plants for local tribes that are becoming scarce in their areas (The Botanic Garden of Smith College). These plants are not conventionally attractive in the collection’s outdoor gardens and do not blend in with the brightly colored flowering vines, but they serve an invaluable function in supporting local Indigenous tribes. While some may see this as a sacrifice on the part of the Smith College garden, it is a necessary step in prioritizing historically shut-out partnerships and needs.

Partnerships and communication are highly effective and important steps in deconstructing colonist patterns, but botanic gardens must take it a step further and begin to decolonize their knowledge base. Knowledge informs action and action informs futures. Because “the knowledge one chooses to produce informs how one chooses to act in the world,” gardens can work towards a less settler-dominated future by producing more Indigenous knowledge (Hassouna). Gardens need to begin to ask, “What kinds of knowledge can benefit fragile ecosystems, environments, and people in the face of environmental change? How can ecological practices contribute to disrupting hegemonic definitions of what counts as knowledge without reinforcing [colonialism]?” (Hassouna). This decolonization of knowledge could look like research led by Indigenous groups, documenting endangered native plants before they go extinct, or engaging in community outreach to make botanic knowledge more accessible to broader populations outside the settler hierarchy.

So, by this point, we can recognize the problematic pasts, understand the present legacies that exert settler power, and begin to enact projects that combat that power, but a garden must still work to ensure that it is making the right choices in these complex projects. Many gardens are turning to rewriting guiding documents such as Collections Management Plans to offer guideposts and checkpoints across their restructuring. While a collections management plan is unique to each garden, through interdisciplinary collaboration, a botanic garden must create a plan to reinvigorate and guide current plans and policies. By continually referring to a written set of goals–such as removing colonialism and racism where possible and interpreting and acknowledging it where it cannot be avoided–botanic gardens can have a set of standards to refer to in order to make consistent changes (The Botanic Garden of Smith College). These plans are best written in collaboration with the communities and partners that they affect. Interdisciplinary and cross-community collaboration in management plans is fairly new and most gardens have not yet taken this step. The gardens at the forefront of decolonization are beginning to have intricate conversations with community leaders of the groups most oppressed by colonizer power structures, but this structure of dialogue still has a long way to go to become a widespread method.

Setting out on this path towards decolonization makes two things abundantly clear. The first: decolonizing is not an easy task. The second: it is a process that must happen. Through community outreach, redesign of collections management, and intentional anti-colonial research, botanic gardens can become socially relevant organizations and enact significant positive changes. Indigenous communities and botanic gardens can create strong partnerships after acknowledging the complicated historical legacies they have to unpack. To continue to have a place to exist and grow in a rapidly changing society, botanic gardens can and must recognize their hierarchies, colonialism, and biases to redesign and reinvest their energy and resources toward an equitable future.

Works Cited

Belfi, E., and N. Sandiford. “What Is Decolonization, Why is it Important, and How Can We Practice It?” Community-Based Global Learning Collaborative,” 2021. www.cbglcollab.org/what-is-decolonization-why-is-it-important.

Berryhill, John. Guest Lecture. Writing 119 – Restoring the Planet, Smith College, 17 September 2024. Smith College Botanic Garden, Northampton, MA.

Berryhill, John. Untitled. Photograph. 14 March 2023. Smith College Botanic Garden.

Blais, Hélène. “Botanical Gardens in Colonial Empires.” Encyclopédie d’Histoire Numérique de L’Europe, 2020. ehne.fr/en/encyclopedia/themes/ecology-and-environment-in-europe/environment-and-colonial-empires/botanical-gardens-in-colonial-empires.

The Botanic Garden of Smith College. “Collections Management Plan for the Outdoor Collections of the Botanic Garden of Smith College.” Moodle, uploaded Magdalena Zapędowska, September 2024, moodle.smith.edu.

Cuerrier, Alain. “Partnering With Indigenous Communities.” BGjournal, vol. 16, no. 1, 2019, pp. 30-32. EBSCO Academic Search Ultimate.

Hassouna, Silvua. “Cultivating biodiverse futures at the (postcolonial) botanical garden.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 49, no. 2, 2024, EBSCO Academic Search Ultimate, https://doi-org.libproxy.smith.edu/10.1111/tran.12639.

Janes, Robert R. “Rethinking Museum Collections in a Troubled World.” Active Collections, ed. Elizabeth Wood, Rainey Tisdale, and Trevor Jones, Routledge, 2017. EBSCO Academic Search Ultimate, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315145150.

Neves, Katja Grötzner. “Botanic Gardens in Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainability: History, Contemporary Engagements, Decolonization Challenges, and Renewed Potential.” Journal of Zoological and Botanical Gardens, vol. 5, no. 2, 2024, pp. 260–275, EBSCO Academic Search Ultimate, https://doi.org/10.3390/jzbg5020018.

Photographer unknown. “Edward J. Canning, Head Gardner, with students in Lyman Plant house, Smith College, 1903-04.” Photograph. Smith College Special Collections, Smith College Archives. https://compass.fivecolleges.edu/islandora/object/smith%3A1373598

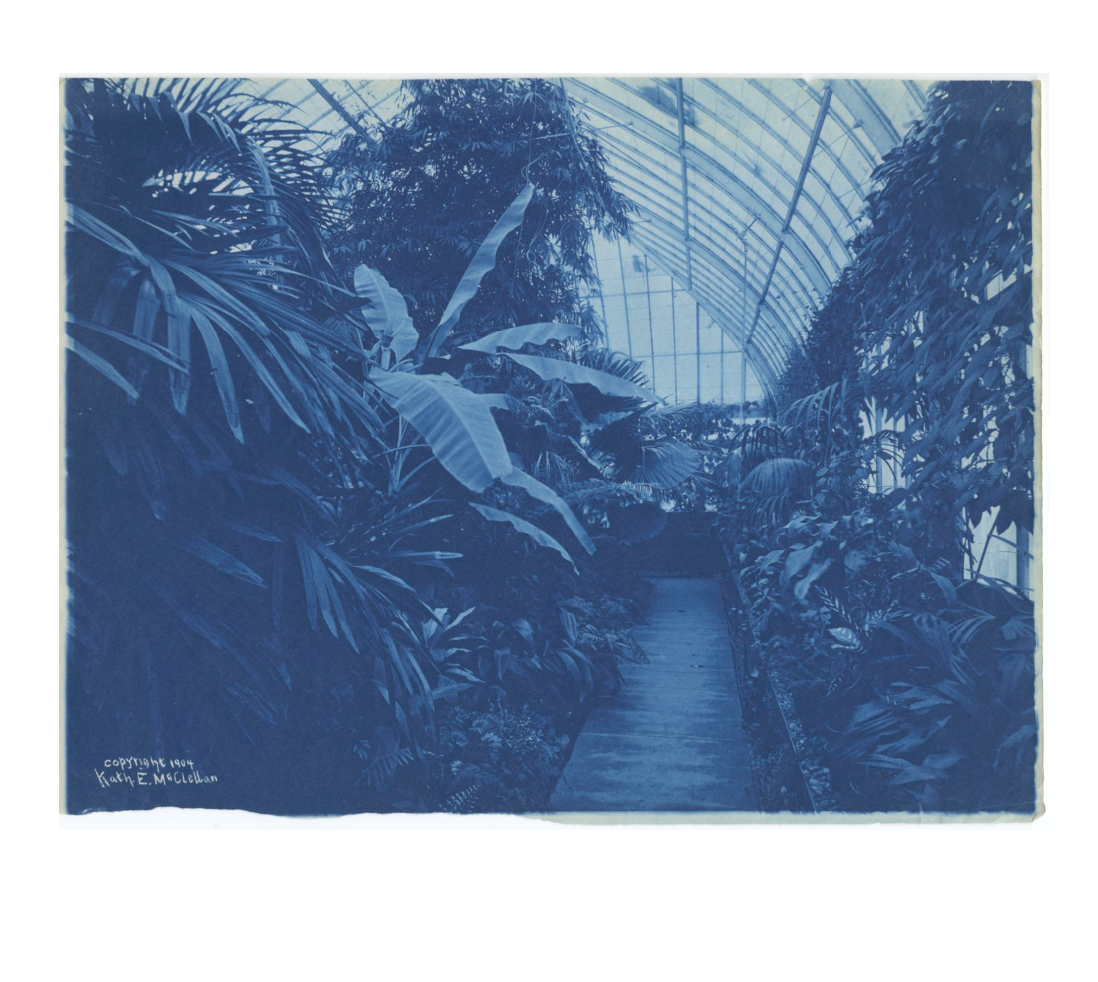

Photographer unknown. “Palm Room in Lyman Plant House, Smith College Botanic Garden, 1904. Smith College Special Collections, Buildings Records. 1904. https://compass.fivecolleges.edu/islandora/object/smith%3A1373266

Scranton, Jessica. Untitled (“Conservation Intern Avery Maltz…”). Photograph. 18 June 2024. Smith College.

Scranton, Jessica. Untitled (“The botanic garden conservation team…”). Photograph. 18 June 2024. Smith College.

Thebiblioholic, “Fall Chrysanthemum Show at the Botanic Garden of Smith College.” Photograph. 20 November 2018. Flickr.

The Botanic Garden of Smith College. “Our 2023-24 Impact: Conservation, Collaboration, and Student Leadership.” Smith College, The Botanic Garden of Smith College, https://garden.smith.edu/impact. Accessed 17 November, 2024.

Recent Comments