“Life as a Soundtrack” by Mikayla Daniel offers a deep dive into the life of a man named Ivory, exploring his journey from casual music listener, to DJ, to media mogul, through near-microscopic detail of his relationship with music. This essay is part playlist, part exploration of the genre of rap and how it differs from coast to coast, but most of all a love letter to music through an interview of a man who needed to feel music intimately in every step of his life. By mixing interview and essay, Daniel expertly explains this love by noting that to Ivory, “Music was ubiquitous.” This essay reminds us of the intrinsic role music plays in our lives–and that there’s a new genre to explore waiting just down the street.–Mars Sell ‘26

Life as a Soundtrack

Mikayla Daniel ’28

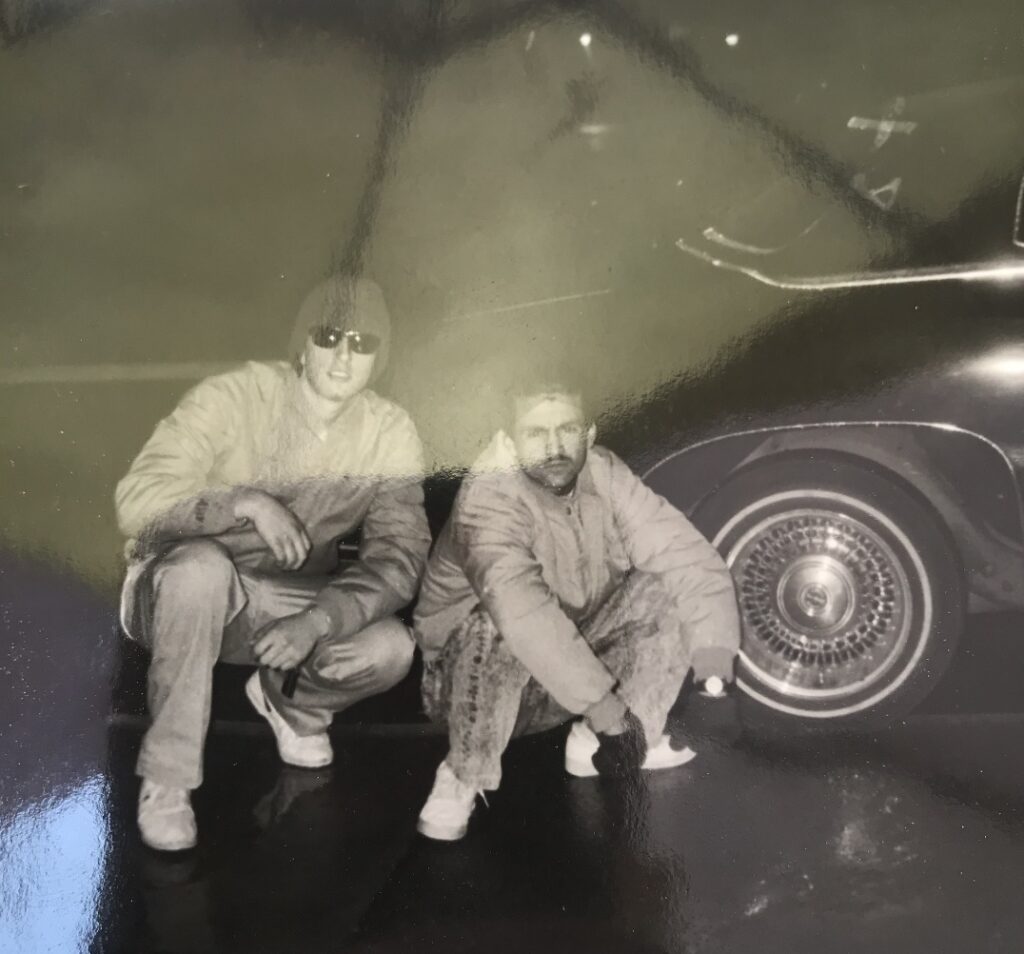

“I had a car when I was 14 that I wasn’t supposed to have. This was a Honda Accord hatchback. It was missing a driver’s side window, which I put plastic up for. But one of the first things we did was we went and got house stereo speakers. And we found our way into getting some car stereos and speakers that would go into the car doors. It was so important to us to have music in this car. One day we were working on putting a sound system in the car. That meant cutting holes out of the doors to put the speakers in, wiring a big speaker to underneath the hatchback and the trunk, and picking which radio we were going to install, because at the time, “for some reason,” we had multiple radios. These were tape decks, called pull-outs. We had Kenwood, Alpine, and Pioneer. So inside the car we had all these wires, multiple sets of speakers, and two or three tape decks on the front floor of the passenger side. But we had steak knives in the car because we were using them to cut the speaker holes out of the door. A friend of mine–a guy named Jason, who we called Little Ivory–had slept over the night before and wanted a ride home. You gotta remember I’m 14: I don’t have a driver’s license, and I don’t have any paperwork on the car. We’re not doing an interview on how I got the car; that’s a different conversation. But the point is that I was with my friend Chad, and Jason wanted a ride home. I told him I didn’t think it made sense because it was a Saturday morning and he lived near a police station. But he said he was going to get in a ton of trouble if he didn’t get home immediately, and he couldn’t take the bus or walk. So I drove him home, and after dropping him off, Chad and I were making a right turn onto Vanowen Boulevard. Before we made the turn, a cop car drove past us and literally kept going. But when I turned, I got uncomfortable because something didn’t feel right. So I turned back onto another street and within not even two minutes, the cop car that had driven way past us was behind us, lighting us up, because they also got a feeling. So that day… I had issues with the police. The car got impounded. And the reason I’m telling you all this is because aside from not having paperwork, the biggest issue the police had for wanting to arrest us was all of the stereo equipment. They said, where did we get it? How could a 14-year-old, and Chad being 15, have three car stereos on the floor? And why did we have knives in the car? That’s how important music was, though. All that we cared about was getting music into the car.”–Ivory

Ivory grew up on the west side of Los Angeles and in different parts of the San Fernando Valley. Anyone that knows him knows that he is constantly projecting music. Whether he is controlling the speakers at a get-together, talking about a recent business endeavor, or recounting a story from the past, music always seems to be present. Throughout this interview with him, one of the main themes that emerged was that he views music as an ever-present soundtrack to his life. When he enjoys something, he puts everything he has into knowing more about it. And one thing is for sure: if he has a goal, he will reach it. But how did some street kid from LA end up owning 12 multimedia companies with over 50 musical artists, traveling the world for concerts on every scale, and managing some of his childhood musical idols?

Link to playlist with all songs mentioned and songs from each artist mentioned, in order:

Note: Full playlist does not display in WordPress; open in Spotify

“Everything is music; music is sound.”–Ivory

Throughout Ivory’s childhood, there was always music on. He doesn’t remember his first musical memory because there were so many. His mother, Bobbie, was a dancer and acrobat growing up. She played music in the background of everything she was doing. Ivory said that, “if we were in the car, the radio was on, and if we were at home, there was always music on.” This included everything from The Doobie Brothers to David Bowie and lots of what would be considered 70s classic rock nowadays. Bobbie would take him to many concerts from a young age. He distinctly remembers seeing people like The Beach Boys, Luther Vandross, and George Clinton. He even remembers going to an orchestra concert in the park with his mom at around 6 years old. Ivory’s parents divorced when he was very young, around four, so as he grew up, his mother was dating new people who were also musical influences. He remembers one of her boyfriends playing a lot of music in the car and another that played in a band whose shows they would attend. At Ivory’s grandparents’ house they had a box of 45s and LPs that were intriguing to him for as far back as he can remember. He would pick up records and curiously read lyrics and credits from the jackets. Ivory also remembers driving in the car with his grandfather and singing along to artists like Frank Sinatra. Ivory’s aunt and uncle, who loved to dance, lived out in the suburbs where they had a music room with thousands of 45s hanging on the wall. He remembers that at every family event, there was music in the background and people dancing. Shows like Soul Train and American Bandstand were also important to him, and he tried to watch them whenever they were showing. Even when Ivory was with his father Raymond, the radio was perpetually on. His dad was very into Motown, so artists like The Four Tops and The Temptations would play alongside 50s music such as Elvis and doo-wop.

Growing up in Ivory’s neighborhood in West LA, there was complete cultural diversity. He lived in a very tight-knit neighborhood. Although coming from different cultural backgrounds, everyone shared the similarity that out of 10 kids, only one or two had parents who were still together. This meant many things. First off, each family played their own cultural music in addition to whatever was on the radio, which added more early musical influences for Ivory. Secondly, this meant that with working single parents, the neighborhood kids were constantly out together on the streets without parental supervision. The third is best summarized by Ivory himself: “I think there’s some influence of lifestyle when you have a single parent who’s also trying to figure their life out and is using music to do so.”

At this point in Ivory’s life–the late 70s and early 80s–there was a bustling hip-hop/rap music culture emerging parallel to his experiences growing up. All the kids in his neighborhood were borderline doing what would be considered “gang activity”; alongside that, they took a liking to the rap music culture in California. The radio station KDAY–one of the first hip-hop stations in the country–featured Friday Night Live and Saturday Night Fresh, which had live mixing on the air. This was a big deal for Ivory because if you turned on 1580 AM, you could hear rap music on the radio all day and night, adding the influence of artists like ICE-T. There were also certain movies released that had a very influential musical impact at the time, some of them being Wild Style, which was about music and graffiti, and Beat Street, which focused on the East Coast hip-hop culture and was one of the first hip-hop movies. During this time, there were also important mainstream musical events occurring, such as Blondie putting out “Rapture,” making her one of the first pop artists to embrace rap music.

If Ivory and his crew of friends–about 10 people at the time–were doing anything, music was included as often as possible. Whether taking the bus, skateboarding, biking, or walking, they almost always had some form of radio with them. At around eight years old, he spent a lot of time at Venice Beach. He and his friends would bring along a portable tape deck, and upon arrival, see dancers or people on roller skates with guitars creating landscapes that were extremely musically driven. Once Ivory would return to his room, he’d put headphones on and listen to more music, over and over again. While some kids traded baseball cards, these kids traded and shared music. The parents of one of Ivory’s close friends, Chad, were from the Bronx. At around nine years old (when Ivory was eight), Chad would go see his dad in New York in the summer, and bring back 12-inch singles to Ivory, introducing even more new sounds.

When asked why he and his friends were so drawn to the rap music that he heavily associates with certain periods of his youth, Ivory replied, “I think it might be that we thought we related to the lyrics. We all loved the beat. We loved the dancing culture and graffiti culture that was going with it. Now that I’m 51, obviously I’m in the music business, but when I’m talking to people, I always tell my clients or artists that our mission is to make the music we put out be the soundtrack to people’s lives versus selling them something that needs to be forced on them. If you can make the soundtrack to their life, they naturally want to listen to it, and I think that’s what was happening. We were already listening to a lot of funk, jazz, and hard rock because of our parents, but rap music seemed to connect with us because of all the parts of that culture. Now, where I was at, most of the kids in my neighborhood were more involved with gangs, skateboarding, BMX riding, and all that. But what made us unique was that we had this music as the background to anything we were doing.”

Something prominent to note here is that in Ivory’s life, there was never the experience of parental disapproval that often comes along with new eras of music. When he was very young, his mom taught jazz, tap, and ballet as a side job at night, so as a dancer, she enjoyed and was very supportive of all music. She completely embraced sounds that other kids were told to turn down or off.

But it wasn’t just hip hop or rap that filled Ivory’s youth. At the same time, he had many friends who were very into rock music, and he was buying records by artists like Iron Maiden and Black Flag because on the corner of his street there was a punk rock record store, selling what was seen as completely underground music back then. On the other corner there was a barbershop called Cliffs that was full of music the moment you entered, playing current and classic rock with artists like Bob Seger and The Marshall Tucker Band. Everywhere he turned, literally on every corner, different sounds and genres followed him. Music was ubiquitous.

One album that became a crucial musical foundation for Ivory was The Wall by Pink Floyd. Bobbie took Ivory to see the movie in theaters as soon as it came out, when he was ten years old. Ivory, who had already begun collecting music on his own at around eight years old, became very invested in the album, burning through at least five cassette copies. When asking him about some songs that left an impact, he mentioned “Another Brick in the Wall” from this very album.

“It wasn’t about the point of not needing education. Everything about the song touched me if I look back: the lyrics, the arrangement. I was into the body of work of The Wall at such an early age, so I played it all the way through and then that song over and over. You know… music really was the soundtrack to my life, so I have tons of events that occurred that have singular songs associated with them, good and bad–such as being inside a night club I wasn’t supposed to be at and getting robbed when I was 11 years old, and the song that was playing when that happened: “Request Line” by Rock Master Scott and The Dynamic Three. There was a very famous lyric, which was, “DJ, please pick up your phone.” Also, another song called “The Roof Is On Fire” was tied to that song. So in other words, that music was in my brain, and there are countless lists of things like that in my life with songs connected to events.”–Ivory

Around this time, in 1982, music began to take a new form for Ivory: pause-button mixtapes. In the bedroom of his apartment, he had a stereo with one turntable and one tape recorder. Since mixing was always done with two turntables and a mixer, Ivory, not having anything like this, started making pause-button mixtapes. This meant that he would play a record and record it, hit pause on the tape, stop the record, pull it back, hit pause, and then start mixing–allowing him to take one record and mix it as if it were two.

When Ivory was 12, he bought a mixer from Radio Shack and his first set of turntables, Technics SLB92 belt drive turntables. He remembers exactly what they were called because they were inexpensive, which was how he could afford them. The problem was that once he got these turntables, he realized that they were the wrong type, because for mixing and scratching you need what’s called a direct drive turntable–not a belt drive turntable. Consequently, his next mission was to buy Technique 1200s. (For a little DJ history, these became the main DJ turntables from the early 70s through the early 2000s, when digital turntables and CDs came out.) At 13, Ivory had already begun making and selling mixtapes to his friends. Anywhere he went, he was buying, borrowing, and collecting records while trying to get better at mixing.

“I found a way to intersect music and money at a very young age. Because by the time I was in junior high, I was already selling mixtapes. The whole point of the mixtape that’s funny is that it’s what digital music is now in a weird way, where a mixtape meant that you could have contiguous music of all these different songs coming and going. I was giving 60-minute tapes to the security guards at my high school, who would then let me come and go in the parking lot with that car I wasn’t supposed to have without being bothered. So, I guess the metaphor is understanding the commodity. The music was a commodity already. So, I made music. I was able to trade that for something. Also, at this time, I was doing a lot of house parties. This was when I was 14. And what does that mean? It means that people are having a party in their backyard, so bring your turntables, or they have turntables and you bring a crate of records. Even back then, people being like, hey, I’ll give you 50 bucks to come play.”–Ivory

From 14 to 16, DJing became a crucial part of Ivory’s musical enrichment. If people were ditching school and throwing a party, which happened frequently for these LA kids, Ivory would get the call to DJ. He made money taking the bus to parties, and, being severely underage, he would sneak into clubs on Sunset Boulevard, get up to the booth with his crate, and put on a 45-minute set. He would go out on Friday and Saturday nights as DJ Ivory, with his name on flyers at events.

“DJing for me was very much like people’s sports; it’s something I was very dedicated to and wanted to be really good at. I spent hours upon hours hunting for and listening to new music, practicing, naturally feeling and learning how to–what you might say–rock a party or be the soundtrack to people’s lives. And I’m sure that, you know, it probably felt good getting a high five or a nod at 14 years old from grown-ups because you’re rocking their party.”–Ivory

One aspect that was advantageous when it came to DJing was knowledge of East Coast rap along with West. An influential point in his life was when he met his close friend $tyles. As Ivory was 11, $tyles–who was 15–was basically about to get kicked out of Brooklyn because of “some street shit.” Ivory’s mother, Bobbie, and $tyles’ dad worked together in the garment industry downtown, and $tyles was sent out to LA as a kid to “get it together” and live with his dad. One night when their parents were going out to have dinner, Ivory went over to his house and the kids were left together alone. They immediately became close friends. Since $tyles was such a New Yorker and was deep into hip hop, Ivory was introduced to the music coming out of a place in New York called The Fun House–a very famous gathering spot early on for East Coast rap and hip hop.

Along with the culture of hip-hop and rap came breakdancing. Ivory was in a breakdancing crew called the LA Breakers, while in places like New York there were the Rock Steady crew and others. He had friends who were some of the best breakers and poppers in LA at the time. Although he never became serious about breaking, he was very into popping for a while. To this day, he might, every once in a while, pop to songs like “Egypt Egypt,” “Electric Kingdom,” and “Play at Your Own Risk” when hanging out late at night with his close friend since about five years old, Alex–a.k.a Big Al.

As Ivory got older, he transitioned smoothly from DJing to promoting, still at a very young age. The thought pattern was, if he was going create the soundtrack for these people, he might as well also get the money from them walking in the door. He already had a network through music, which led to DJing and throwing events such as backyard parties. There was also a whole era of events called “underground/map parties” in LA that took place in the downtown warehouse district. This was before iPhones, so the only way you could hear about them was through hand-to-hand flyers and a map that you wouldn’t get until the morning of the party (because with a thousand people in a venue, they were illegal).

Once Ivory started really driving–with a license–he found a new interest, the lowrider scene. As he entered this world, he realized he didn’t want to DJ for money anymore, and it became more of a hobby. Ivory mixed at home; and since there were always get-togethers with his buddies, they would rotate who was mixing at the moment. He became extremely interested in the world of these hydraulic cars. Of course, this meant that he needed to integrate his love for music into his new hobby. He made new soundtracks for driving and continued to be completely inundated with music, purchasing equipment and drum machines while always looking for ways to get more music and to connect with people who worked at record stores. As he was working on a new car, the most important thing for him was preparing the sound system. He wanted to have competition sound systems, meaning a car that was not only louder than others but clearer. “Everybody could turn it up,” he says, but that didn’t matter without clarity. He had already gathered the entire sound system for this car–Cerwin Vega 12-inch woofers for the trunk and Pioneer 6x9s–in his closet before he could even drive it. Ivory also had a device called an Epicenter: a button he could pull that would enhance the bass. This lowrider hobby led to Ivory attending car shows with live bands such as Malo, Tierra, and El Chicano, and gave him musical influences in this lifestyle genre–artists like James Brown, Ohio Players, Zapp, Rick James, Tower of Power (who he now manages), Keith Sweat, Marvin Gaye, Parliament, and Funkadelic (and then, eventually, modern funk masters such as his management client LETTUCE). Around the same time, he also had influences from the California Bay Area, artists such as E-40 and Too $hort, who had a heavy impact on West Coast Hip Hop during this period.

If it’s not clear by now, when Ivory likes something, he takes a deep dive into it and strives to do his best. His father was a hairdresser, and Ivory remembers that even if he was just sweeping the floors at a hair salon, he tried to be the best hair-sweeper he could be. As anyone who knows Ivory would attest to, if he’s ironing the creases in his jeans, as he’d say, his creases are going to be “extremely crispy.” This entire mentality seeped into his actions, elevating the power of music in his life. If Ivory was going to play music for others, he wanted it to be the best around. And if he was going to listen to a song, he wanted to explore it deeper, learning every facet of it.

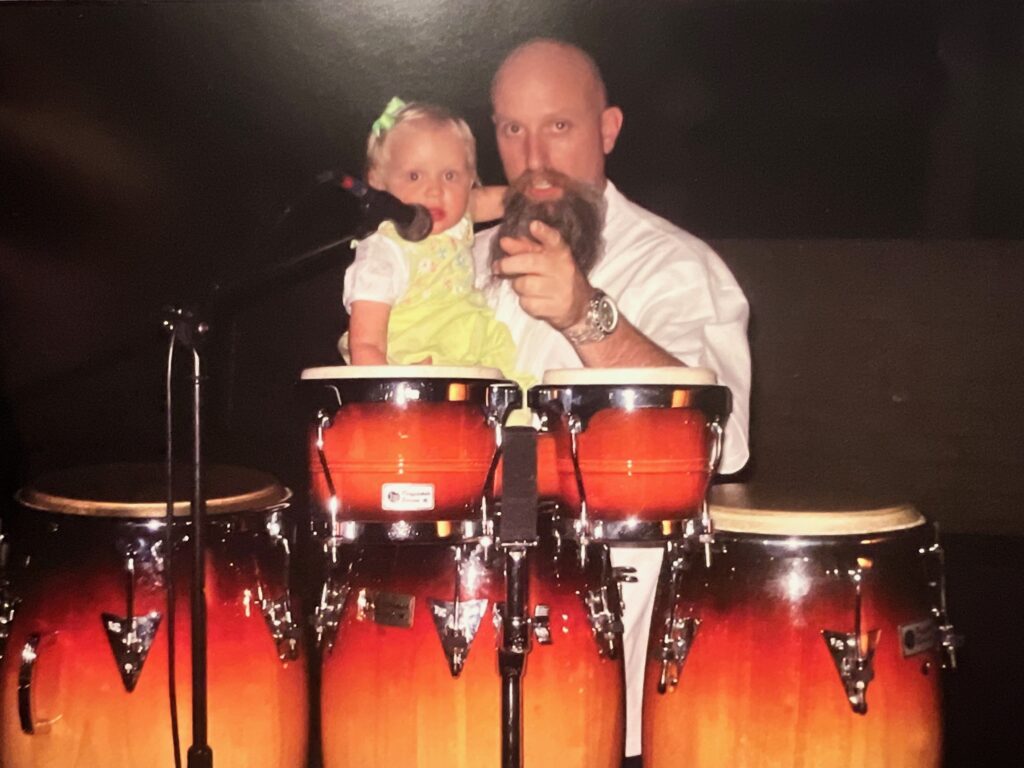

When Ivory was 20, Bobbie said to him, “Hey, let’s have a big birthday for your 21st.” Because he was always–in his mom’s opinion–“doing for others,” she wanted to make an event out of his birthday. The idea was that they should get a live band, since he usually DJed family events, like his uncle Barry’s 45th (or so) birthday, which he did with Chad. So, he and his mom opened the LA Weekly, which was the pinnacle of information for live entertainment in LA. Each club had a listing of upcoming shows; they noticed one in Venice called St. Mark’s, with an artist named Poncho Sanchez playing Latin jazz. At this point, Ivory had collected a lot of jazz music but hadn’t gotten deep into Latin jazz yet. Ivory, Bobbie, and a friend of Bobbie’s named Mappa went and saw this nine-piece band on stage, with the leader Poncho Sanchez playing congas.

Now, at this point in his life, Ivory was already very invested in trying to understand how the music he loved was made. When you think about it, much of the sound he was listening to was heavily driven by percussion: these hip-hop songs held “the beat” at the very core of their function. Music coming out on Tommy Boy records (which is now ironic because Ivory manages artists such as Everlast, DJ Muggs, and House of Pain–who were on Tommy Boy back in the day) played a large role for Ivory at the time, along with Zulu Nation, Trinere, The Art of Noise, and Krawftwerk. There were also very influential rap songs emerging along with the presence of groups like The Sugarhill Gang, Boogie Down Productions, and World Class Wreckin’ Cru. The point being: all around Ivory, and in terms of both East and West Coast, there was a lot of impactful instrumental music. Plus, each time he got a 12-inch vinyl, the B-side typically had an instrumental version. Behind these songs, percussion and Latin music were involved because in many old hip-hop records with a high bpm, there were instruments like bongos, cowbells, congas, and shakers that came out of AfroCuban music and culture. All of this sound was part of what Ivory was mixing and trying to emulate on drum machines daily.

“So, all of a sudden, I’m looking at this guy playing these drums that were an integral part of the hip-hop music I was into. You also had a bongo player and a timbale player, and if you put those three together, you realize you could make almost all the drum patterns that I was DJing with–except they were electronic. So I watched him, and I was fascinated.

“X amount of years later, I manage Poncho. I’ve managed him now for over 17 years. But the point is that the day after seeing that show, I bought a pair of congas–didn’t know anything about playing them. I also went to Tower Records and bought every Poncho Sanchez CD I could find. I looked at the guests he had on his CDs, which led me to buying CDs from Mongo Santamaria, Dizzy Gillespie, Fania All Stars, and Cal Tjader–all these artists that were in Poncho’s ecosystem. When I look back, that gave me some of the most legendary jazz musicians that ever lived, their music. From that point forward, I immediately became addicted to Latin music. When I say Latin, I don’t mean like how I grew up in L.A., which is more of the Chicano culture–and with that said, Southern California, that’s a whole other chapter of the influence. But this became the island culture: Puerto Rico, Cuba, Brazil, South America.”–Ivory

This led to Ivory’s next passion/hobby: congas. He started studying with a man named Micheal who played every instrument percussion-wise and had experience performing in settings ranging from bands to orchestras and Broadway. When Ivory started off with him, knowing nothing, he just said he wanted to play like Poncho Sanchez. But soon after, he was asked if he really wanted to understand the music or “just memorize songs,” to which Ivory–of course–said he wanted to really understand. This meant that for a while he didn’t play drums, first focusing on learning clave (meaning key in Spanish). Once again, through this interest he found more and more music. For example, an important artist for him at the time was Santana. Another huge influence for him then became the group War, who he now manages. War mixed percussion and funk with real strong structure rather than just “jamming,” and he became a big fan of theirs, with one of his favorite songs ever being “Slippin’ Into Darkness.”

For hours Ivory and his friend Alex, who was multilingual, would listen to new songs in Spanish. Al translated certain lyrics for Ivory, helping him have a better understanding of the music, along with “how the percussion and lyrics lived together in the body of work.” He was obsessed with different styles: from cha cha to salsa, mambo, and rumba. He practiced every single day and constantly went to see as much live music as he could. He didn’t have intentions of performing in front of anyone, but he loved playing so much and worked hard enough that if he went somewhere and there was a band playing, he might end up sitting in.

At the turn of any event that had an impact on his life, Ivory said that there was almost always music playing. When his close friend who was like a brother passed away very young, Ivory remembers the music that his friend had been listening to before he was killed: Above the Law and Funkdoobiest. When the memorial took place, “What a Wonderful World” by Louis Armstrong was playing. Since Ivory strongly associates music with memories, he explained that he can hear that song at any moment and then make the choice of either being in the mood where it makes him want to cry, thinking about that tragedy, or the mood in which he focuses on the beauty of the memorial. Ivory thinks that most things are felt based on how the receiver chooses to take them, and when we then receive music, we subconsciously know how a song will translate into our lives. This has been the case for him many times.

“I think music was a definite driver of emotion for me. Probably more than almost anything. And I would say it still is. I’ve been to a million funerals and maybe not cried at… 80% of them. But throw me on the 101 on my motorcycle with a song in my ears, and I’ll be going 100 with tears coming out of my eyes.”–Ivory

Ivory also hears music differently at this point in his life than he used to. Sometimes, one of the first things he does is think about the business side of what he’s hearing when it comes to new music, wondering about the commercial aspect of the art and if it can be popular in any particular genre. Even with older music, he may wonder if the catalog is being marketed right or serviced correctly. For him, that thought pattern is engrained from years of loving music so much but also making a living from it. However, Ivory’s favorite part about what he does is that he doesn’t feel like he truly “has a job”: everything he works on somehow has to do with music, something he truly loves. Through working in the industry, he is also constantly motivated to listen to new artists, continuously expanding his musical horizons.

As a whole, Ivory sees the amount of music that has filled and continues to fill his life as a huge privilege that has opened him up intellectually to those around him. He explained that having such a diverse musical background–or just quantity of music–has allowed him to always find a way to connect with others.

“No matter who I met, I was able to find something in common with them through music. That’s a big bond between communities and friends. And I think it continues to help me have unique interpersonal relationships with people, because you can always find something you have to talk about musically.”–Ivory

“I am fascinated by and love the process of making music and watching it being made. If people take the time and they’re lucky enough to see human beings go in a room with just an idea and then come out with a song, that’s a magical experience, which sounds corny–but it’s magical. For the people that have known me from the beginning of my being in the music business–let’s say $tyles, Al, any of them–the thing we laugh about the most is that I’m doing the exact same thing I’ve been doing for the last three decades, which is somehow putting music out to the world, making money from it, and caring about the music–but just with different wisdom and on a different scale.”–Ivory

Although this interview doesn’t explore Ivory’s entire musical history, one thing is clear: Ivory truly lives and experiences his life as a soundtrack. He holds a uniquely deep appreciation and love for music. His musical library is a representation of the way he grew up, a reflection of his origins, and a painting of the person he molded himself into–despite and because of obstacles he has faced. Ivory has countless influences from those he has crossed paths with, who have brought new sounds into his life, and yet he has introduced music to so many others in turn. He found a way to incorporate something he is so clearly passionate about into his daily life, with music filling each second in one way or another, and he has used his unique skills and intelligence to bring more music to the world by putting out records, putting on concerts, and supporting artists who play a crucial role for their listeners each and every day.

At the end of this interview, Ivory was asked to choose one song that he would want to represent him. He replied by saying, “It sounds funny, but I’d almost say ‘My Way’ by Frank Sinatra. There’s definitely some unique lyrical parallels there.”

All photos courtesy of the author and her family.

Recent Comments