By D. Gordon

By D. Gordon

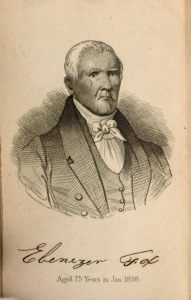

As Ebenezer Fox neared the end of his life, he felt compelled to produce a manuscript of his experience as a young patriot during the Revolutionary War “with the hope that it may prove as interesting to the raising generation, as it has to my own grandchildren.” His autobiography, written in 1838 when he was 75 years old, recounts his experience growing up in Massachusetts and later leaving home as a teenager seeking adventure and an experience out at sea. Fox first worked as a cabin boy aboard a vessel traveling to the French colony of St. Domingue (today’s Haiti) and then returned to the colonies to work as an apprentice for a wigmaker and barber in Boston.

After a brief stint as a replacement soldier during the early years of the war, the 17-year-old Fox joined the American navy in 1780 as a sailor battling British fighting vessels along the Atlantic coast. For the next three years, Fox experienced both the exhilarating glories of winning sea battles and the deep despondency of being a war prisoner. Throughout his perilous adventures at sea, Fox maintained his conviction in the pursuit of liberty and a sense of optimistic perseverance, no matter how precarious his situation was. The excerpts below are taken from Fox’s autobiographical manuscripts. The first section recounts his recruitment process and the general atmosphere in the colonies during the midst of the Revolutionary War in 1780. The second section details Fox’s experience as a prisoner of war just a few months after he first joined the colonial navy.

I continued to perform my duties in the shop, and was contented with my employment till I was about seventeen years of age, when a spirit of roving once more got possession of me; and I expressed a desire to go to sea. The condition of the country was at this time distressing: and, as my master had not more business than he and one apprentice could perform, he expressed a willingness to consent, upon condition that he should receive on half of my wages and the same proportion of whatever prize money might fall to my share.

Our coast was lined with British cruisers, which had almost annihilated our commerce; and the state of Massachusetts judged it expedient to build a government vessel, rated as a twenty-gun ship named the “Protector,” commanded by Captain John Foster Williams. She was to be fitted for service as soon as possible, to protect our commerce, and to annoy the enemy. A rendezvous was established for recruits at the head of Hancock’s wharf, where the national flag, then bearing thirteen stripes and stars, was hoisted. All means were resorted to, which ingenuity could devise, to induce men to enlist. A recruiting officer, bearing a flag and attended by a band of martial music, paraded the streets, to excite a thirst for glory and a spirit of military ambition.

The recruiting officer possessed the qualifications requisite to make the service appear alluring, especially to the young. He was a jovial, good-natured fellow, of ready wit and much broad humor. Crowds followed in his wake when he marched the streets; and he occasionally stopped at the corners to harangue the multitude in order to excite their patriotism and zeal for the cause of liberty.

When he espied any large boys among the idle crowd around him, he would attract their attention by singing in a comical manner the following doggerel:

“All you that have bad masters,

And cannot get your due;

Come, come, my brave boys,

And join with our ship’s crew.”

A shout and a huzza would follow, and some would join in the ranks. My excitable feelings were roused; I repaired to the rendezvous, signed the ship’s papers, mounted a cockade, and was in my own estimation already more than a half of a sailor. The ship was as yet far from being supplied with her complement of men; and the recruiting business went on slowly. Appeals continued to be made to the patriotism of every young man to lend his aid, by his exertions on sea or land, to free his country from the common enemy.

[A few months later, after Fox enlisted in the navy, he was captured by the British army. The following excerpt describes his experience while sitting in jail on a British ship called the Jersey.]

The miseries of our condition were continually increasing: the pestilence on board spread rapidly, and every day added to our bill of mortality. The young, in a particular manner, were its most frequent victims. The number of the prisoners was continually increasing, notwithstanding the frequent and successful attempts to escape: and when we were mustered and called upon to answer to our names, and it was ascertained that nearly two hundred had mysteriously disappeared without leaving any information of their departure, the officers of the ship endeavored to make amends for their past remissness by increasing the rigor of our confinement, and depriving us of all hope of adopting any of the means for liberating ourselves from our cruel thraldom, so successfully practised by many of our comrades.

With the hope that some relief might be obtained to meliorate the wretchedness of our situation, the prisoners petitioned Gen. Clinton, commanding the British forces in New York, for permission to send a memorial to General Washington, describing our condition, and requesting his influence in our behalf, that some exchange of prisoners might be effected.

Permission was obtained, and the memorial was sent. In a few days, an answer was received from Gen. Washington, containing expressions full of interest and sympathy, but declaring his inability to do anything for our relief by way of exchange, as his authority did not extend to the marine department of the service, and that soldiers could not consistently be exchanged for sailors. He declared his intention however to lay our memorial before Congress, and that no exertion should be spared by him to mitigate our sufferings.

Gen. Washington at the same time sent letters to Gen. Clinton, and to the British Commissary of Prisoners, in which he remonstrated against their cruel treatment of the American prisoners, and threatened, if our situation was not made more tolerable, to retaliate by placing British prisoners in circumstances as rigorous and uncomfortable as were our own: that “with what measure they meted the same should be measured to them again.”

Discussion Questions

-

- What do you think was the most important motivation for Ebenezer Fox to get involved in the war effort? Do you think it is aligned with most marines/soldiers of his age?

- Fox wrote about these events nearly 50 years after they transpired. Does that affect your reading of this excerpt? How?

- Closely read the song lyrics in the first excerpt. What are its implications?

- Was the imprisoned sailors’ correspondence with George Washington surprising? If so, why?

Source

Fox, Ebenezer. The Revolutionary Adventures of Ebenezer Fox. Boston: Munroe & Francis, 1838.