Reminder! Sign up now for Water Inquiry Teacher Group July 1 Workshop.

E-mail cberner@smith.edu

How does a first grade teacher engage children in learning about the water cycle?

Heading to Jackson Street School, water inquiry team member Hannah Searles observed Katy Butler’s first grade class and their initial explorations into the water cycle. Ms. Butler sparked students’ interest through reading, class conversations, singing and fun experiments surrounding the water cycle. The exploration culminated in a creative writing assignment, where students combined imagination and acquired knowledge to narrate the life cycle of a water droplet. Examining both components of this inquiry allows us to recognize areas of student interest and opportunities for further avenues of exploration.

Engaging student’s imagination and building foundations

To begin, the class read the picture book All the Water in the World is All the Water in the World by George Ella Lyon. This beautifully illustrated book introduces the idea of the water cycle and water’s ability to travel all around the world in various forms. Hearing that they were drinking the same water the Vikings did was extremely exciting for the students!

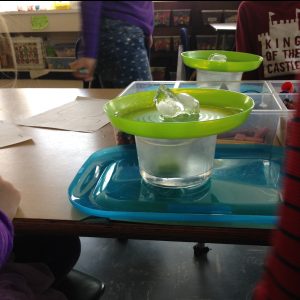

To observe the water cycle in action, the students conducted a simple experiment, involving two plastic cups, a sponge, water and a plate. The larger plastic cup represented the world, while the smaller cup with the sponge in it was the land. The warm water inside was the ocean, and the plate with the ice on top of it was the clouds. The goal of the experiment was to see if the sponge would get wet – if it did, it meant that it had rained. The warm water in combination with the cold plate caused condensation, which then dripped onto the sponge.

Students recorded their observations and got a chance to see for themselves what the water cycle looks like. Click here to download the lesson.

Students also participated in an artistic activity displaying the water cycle. Using shaving cream, food coloring, and a plastic cup of water, the class simulated a rainstorm. This project gets a little messy, so it’s helpful to have grownups in charge of the shaving cream and food coloring.

The water in the cup represented the air in the atmosphere, and the shaving cream sitting on top of it was a cloud. When food coloring poured onto the shaving cream, it “rained” from the cloud and into the water, creating beautiful patterns that let students see what precipitation looks like.

Then, using a plastic straw, the students swirled the shaving cream around and pressed pieces of paper on top, creating beautiful marbled art. This activity let students think both scientifically and creatively. Click here to download the lesson.

How do first graders explain and imagine the water cycle?

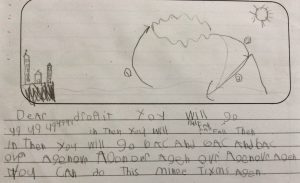

To assess student understanding, Ms. Butler asked students to write to a water droplet using pictures and words to explain the water cycle: “Today you will write a postcard to a water droplet. You will tell the water droplet what will happen to it during its life cycle. You can use words like first, next, then and finally. You get to choose where your water droplet starts in the cycle!” The children’s work reveals interesting patterns, questions, and areas for further inquiry.

Motion and repetition are recurring themes highlighted in children’s drawings and text. The postcard pictured above is a salient example of how children repeat words and symbols multiple times to show their understanding of the water cycle. Up, fall, again are the most frequently repeated words. Water drops, clouds and arrows (always shown clockwise) are the most frequently repeated visual images.

Water cycle vocabulary words appear in most of the postcards, more often in the written text than in the drawings. Although there is some variation in the order, most children choose to show or write the terms in the sequence: precipitation, condensation, evaporation. It’s interesting to think about the connection between the children’s use of water cycle vocabulary words and their ideas about motion, repetition, and what they can observe in the world around them.

Visual elements in drawings include (in order of frequency): clouds, rain drops, water, arrows, buildings, ocean and topography (mountains/hills). Anomalies (each appearing in only one drawing) include: the sun, lightning, volcano, and a viking beard.

The imaginative prompt “Dear Droplet” activates children’s imagination and curiosity:

- “What is like to go all around the world?”

- “You will have a blast.”

- “You might get drinkt and that somebody might be me. You’re probably Viking beard water.”

Children’s questions and theories about how water travels around the water cycle point to further possibilities for inquiry and investigation:

- “You will go around the world.”

- “You will start in the ocean… end up in the same place.”

- “Dear water droplet where are you?

Are you in New York?…

Are you in Northampton?

Are you in Greece?”

Areas for further inquiry emerge from what’s featured and what’s missing in the first graders’ explanations. For example, the infrequent appearance of the the sun (only once), rivers, lakes and groundwater suggest new questions to investigate:

- What does the sun have to do with the water cycle?

- How does water travel to the ocean?

- Can we SEE the water cycle? Where? Why or why not? – This could lead to a schoolyard scavenger hunt -style investigation over several weeks looking for evidence of precipitation, evaporation, and condensation.

Join the conversation

These activities are just snapshots of some of the ongoing water studies that teachers are doing with their students. What are you doing with your students? What seems exciting about water to them?

Blog post by Hannah Searles, Ally Ciccarone, and Carol Berner