“Making Democracy Real” offers a historical overview of African American women’s efforts to gain access to contraception, from the early stirrings of the campaign to legalize birth control in the 1910s to the eve of mass movements for racial equality and women’s rights in the 1960s. The birth control struggle becomes a window on the racial, gender, and economic structures black women negotiated in pursuit of sexual and reproductive self-determination at that time. Taking us back a century, and with emphasis on resilience and resistance, their story reminds us of the deep roots and broad vision of black women’s leadership in what has become a women-of-color-led human rights movement for reproductive justice today.

The essay is part of a larger initiative to “put history into action.” It began with the Voices of Feminism Project, a decade-long project of the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College to preserve the records and oral histories of women marginalized in dominant historical narratives (http://www.smith.edu/libraries/libs/ssc/vof/vof-intro.html). That documentation process seeded a commitment to forge activist-academic partnerships that develop the materials and insights activists entrust to the archives into resources they can apply to ongoing campaigns for social change.

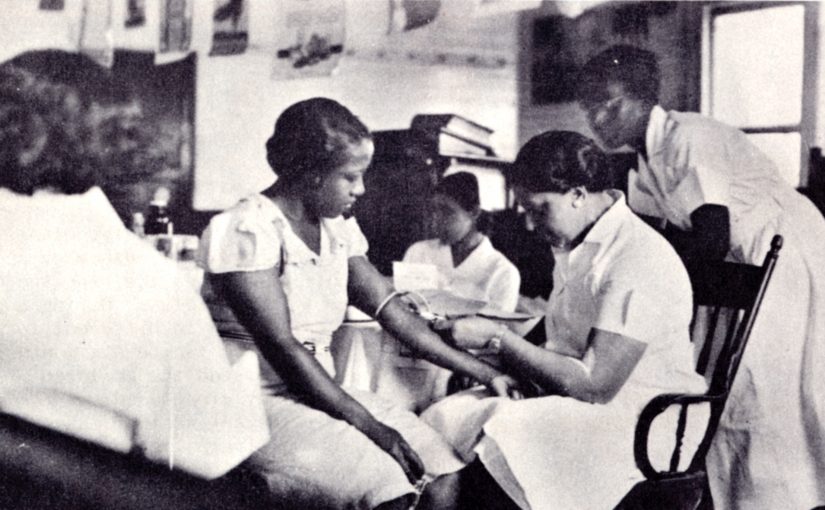

The occasion arose in 2010 when anti-abortion groups launched a racialized campaign to recriminalize abortion. The legislative and advocacy campaign featured billboards depicting black children as an “endangered species.” That strategy relied on a carefully constructed and distorted historical narrative that erased centuries of black women’s organizing to control their fertility, disregarded the complexities of their reproductive lives, and portrayed them as passive victims of a genocidal plan targeting the black community. When the Sophia Smith Collection provided reproductive justice activists with four documents illustrating black women’s activism for birth control in the early 20th century, that small intervention had significant results. The tangible evidence of women’s agency and ideas contributed to defeat of anti-abortion legislation, and it emboldened young African American activists, who gained appreciation for little-known foremothers and came to see themselves as carrying on a long struggle.*

That episode inspired this essay to bring historical perspective to bear on current debates and to call attention to the wealth of archival resources on reproductive health, rights, and justice. (For the Sophia Smith Collection, see https://www.smith.edu/libraries/special-collections/research-collections/resources-subject/womens-health). It also inspired the Steinem Initiative, a two-year experiment in designing tools that make historical knowledge, archival evidence, and documentation methods accessible to organizers. One outcome of the Initiative is a Reproductive Justice History in Action Project that is expanding on this essay and building an interactive digital toolkit to place the long histories of indigenous women, women of color, queer women, and low-income women organizing for sexual and reproductive health, rights and justice in the U.S. in the hands of activists for use in strategy development and movement building today.

*For an account of this episode by one of the principals, see Loretta J. Ross, “Trust Black Women: Reproductive Justice and Eugenics,” in Loretta J. Ross, et al, eds., Radical Reproductive Justice: Foundations, Theory, Practice, Critique (NY: Feminist Press, 2017), 58-85.

◊ ◊ ◊

This site contains embedded copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. These materials are being made available for the purpose of advancing understanding of U.S. women’s history. The author believes this constitutes a “fair use” of such material as provided in US Copyright Law and is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond “fair use,” you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.