In 1941, the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) passed a resolution endorsing birth control. With this action, black women stepped to the forefront of the movement. Most major white women’s groups, such as the League of Women Voters, the U.S. Children’s Bureau, and the National Woman’s Party, still avoided the controversial issue of contraception. The Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) had taken a stand for legalization but conditioned its support on distribution by medical professionals.14

The National Council of Negro Women took a different approach. The NCNW was a coalition of black women’s clubs with expansive plans of action for improved education, housing, child care, employment, and health. In the 1940s the NCNW claimed to represent a million women. Its position on birth control was typical of black women reformers’ record of underscoring the prevalence of rape and integrating sexual and reproductive self-determination into agendas for racial and economic progress. (Collier-Thomas 1993; Gordon 1991).15

The civil rights leader and educator MARY McLEOD BETHUNE was president of NCNW and a nationally influential spokeswoman. As a member of President Franklin Roosevelt’s “Black Cabinet,” she was the highest-ranking black woman in the federal government. From her position as head of the Office of Minority Affairs of the National Youth Administration, Bethune protested sex and race discrimination in New Deal health and welfare policies and lobbied for black women’s role in setting the national agenda. Florence Rose recognized Bethune as “THE top Negro woman leader in America today.16

Bethune became a staunch and valued ally of the Division of Negro Service. She publicly defended birth control against intense organized opposition from the Catholic Church. Within the black community, her outspoken support lent birth control respectability at a time when many preachers associated it with immorality and some political leaders equated it with genocide or “race suicide.”.

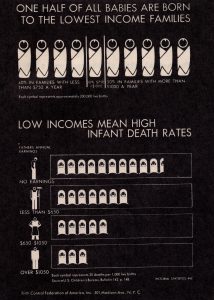

The NCNW resolution in favor of birth control inserted black women’s voices into debates around the scientific merits and political implications of eugenics in controlling the size and composition of the population. Eugenics enjoyed wide acceptance in the interwar years. With the blessing of the Supreme Court’s Buck v. Bell decision, state governments were authorizing the involuntary sterilization of vulnerable individuals they defined as “unfit,” and during the economic crisis of the 1930s, public officials expanded that category to include women who were poor or considered to be “feeble minded” or sexually promiscuous. Coupled with presumptions of white superiority, these policies sometimes targeted black women and intensified fears of race suicide.

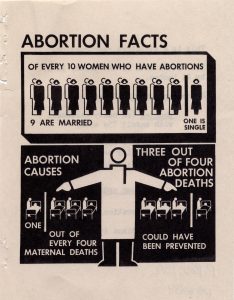

Black women’s argument for birth control combined criticism of eugenics and coerced sterilization with assertions of women’s rights and racial equality. The 1941 resolution stood out for its emphasis on the right to bear as well as not to bear children, and for its focus on the socioeconomic conditions that influenced the ability to rear healthy families. Club women affirmed contraception as an empowering alternative to the threat of involuntary sterilization and to the danger of illegal and self-induced abortion as means of regulating fertility.

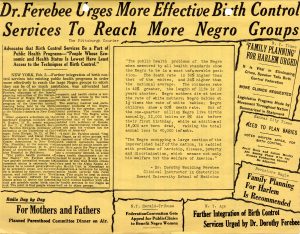

Following passage of the resolution, the NCNW formed a Family Planning Committee, with Dr. Dorothy Ferebee as chair. Ferebee was among many doctors and nurses in the club movement who championed birth control. Because discrimination barred female physicians from practicing in many hospitals and because their patients often could not afford hospital care, black female doctors attended deliveries in women’s homes. Face to face with the toll frequent pregnancies took on women’s health and family life, they understood women’s struggles to control their own sexuality, regulate their fertility, and bear healthy infants as a community challenge rooted in socioeconomic inequalities.

The three health providers featured here — E. Mae McCarroll, M.D., Mabel Keaton Staupers, R.N., and Dorothy Boulding Ferebee, M.D. — incorporated contraception into agendas for racial advancement. They combined professional commitment to public health with leadership in the black women’s club movement and active collaboration with Sanger and Rose and the campaign for birth control.

McCarroll, Staupers, and Ferebee all rallied to the Negro Project. They sat on the National Advisory Council of the Division of Negro Service. With other female medical providers around the country, they formed a speakers bureau to distribute literature, screen films, and offer medical instruction. They encouraged the memberships of African American women’s groups and other civic, religious, educational and professional organizations — from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Elks to the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters — to accept the Division of Negro Service as an ally. As leaders in the NCNW, they carried the backing of this large and significant constituency as they pressed other organizations to accept birth control as a tool of race progress.

E. MAE McCARROLL, M.D.

McCarroll was a clinician with the Department of Health in Newark, New Jersey. In the 1930s, she lectured audiences of women throughout the city on the subject of sexually transmitted diseases and led statewide efforts to combat them. She later earned an M.S. in public health and became the first black physician permitted to practice in the Newark City Hospital. McCarroll chaired the Health Committee of the New Jersey Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs and traveled the country on behalf of the Division of Negro Service. She spoke to many audiences, including the National Negro Business League, the National Housewives League, the Urban League, and the Purple Cross Nurses.

In a 1942 address to the National Medical Association, the professional organization of black doctors, she touted birth control as a “great reform” and urged physicians to join “a national program of education and organization among our own people who have not yet been reached to any large extent by the benefits of Planned Parenthood.” Because it was a woman’s right to decide the number of children she would bear, McCarroll argued, it was therefore the responsibility of private physicians and public health agencies to become knowledgeable about contraceptive techniques and to make family planning information and methods available to all.17 Following her speech, the National Medical Association endorsed the work of the Division of Negro Service. Speaking to Harlem nurses on another occasion, McCarroll presented medical and social arguments for birth control. Appealing to the nurses as women, health providers, and race leaders, she urged them to disseminate contraceptive information to their patients.

MABEL KEATON STAUPERS, R.N.

Staupers devoted her career to challenging race discrimination in medical training and treatment. In the 1920s she helped establish the Booker T. Washington Sanitarium, the first in-patient center in Harlem for black patients with tuberculosis. In the 1930s, as executive secretary of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses, she began a long and ultimately successful battle for the integration of black nurses into the American Nursing Association. She was a co-founder of the National Council of Negro Women and cochaired its Health Committee.

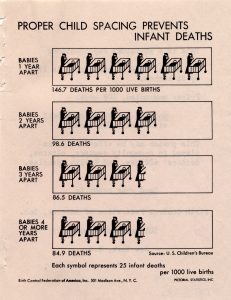

Staupers attended the initial meeting of the Advisory Board of the Harlem Clinic in 1931 and remained committed to its mission. She implored black nurses to accept their special responsibility to educate patients about contraception, not only because nurses had “intimate knowledge … of all the problems arising from ignorance of child spacing and family planning,” but also because black women would be more likely to accept birth control if it was presented “through people in whom they already have confidence.”18

Staupers played a leadership role in National Negro Health Week, an annual campaign of education, screenings, and services, which began at Tuskegee Institute in 1915. By the time the U.S. Public Health Service took over the program in 1932, nearly every black community in the country, rural and urban, hosted events. In 1935, some 2,200 localities organized National Negro Health Week activities. A decade later, the number of sites had grown to 12,500, with millions of people participating. As one of only two women to serve on the National Negro Health Week executive committee from 1935 to 1945, Staupers undoubtedly had something to do with the fact that Planned Parenthood materials became available at the popular spring gatherings.

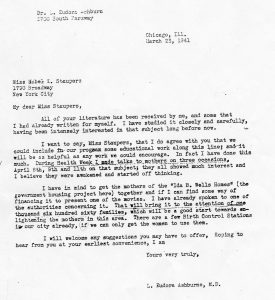

In a letter to Staupers, L Eudora Ashburne, a Chicago physician, attested to the significance of National Negro Health Week as a forum for publicizing birth control. Ashburne also noted that African American women had been organizing for birth control for some time through their own networks, independent of clinics and of Planned Parenthood. They were incorporating Division of Negro Service materials into existing campaigns.

DOROTHY BOULDING FEREBEE, M.D.

Ferebee began teaching obstetrics at Howard University Medical School in the 1920s and was deeply involved in local and national maternal and child welfare programs. When the National Council of Negro Women endorsed birth control in 1941, Ferebee became chair of the Family Planning Committee the Council created to take action.

Ferebee was also medical director of Alpha Kappa Alpha, a sorority of black college women. Each summer from 1935 to 1941, she led teams of AKA volunteers to the Mississippi Delta, where they set up mobile clinics in cotton fields, churches, and schools to deliver basic health care to tenant farmers and sharecroppers, who may not have been examined by a doctor or nurse before. Ferebee described the project as an effort “to enlarge the range of opportunities for the masses by extending the benefit of health to those who struggle against disease and poverty and exploitation.19 Over the several summers, the volunteers provided basic physical examinations, medical treatments, and dietary instruction to more than 15,000 people. A majority of patients were children, many suffering from malnutrition.

Ferebee assured Rose at the Division of Negro Service that she would attempt to introduce birth control to “plantation mothers” through the Mississippi clinics.20 Doing so meant risking the hostility of plantation owners, who were ambivalent at best toward efforts to improve workers’ lot and who had a vested interest in ensuring that black women continued to reproduce an adequate and dependent labor force. Allegations swirled around the AKA women, charging that they were communist agitators whose real motive was inciting tenant farmers to protest. Planters posted “riders” armed with guns and whips to patrol the clinics on horseback and listen in on conversations between health workers and sharecroppers.(Smith 1995, chap. 6).

In their annual reports, AKA women detailed the horrendous living conditions sharecroppers endured. They indicted the plantation economy as a “most vicious system” and noted that the power to control women’s reproductive capacity was an integral part of it. For instance, they observed that when owners inventoried their assets, they counted only those children in tenant families who were old enough to work in the fields.21

Summing up the AKA Mississippi experience in 1941, Ferebee wrote, “The health project…has graphically demonstrated the interrelation of every social and economic activity as a part of a whole. Our observations and studies in the field have reinforced our conviction that the problem of health is one of many facets which link it to the entire social order; for disease is both the cause and result of many miserable social and economic conditions.”

She called the nation to account for condoning such gross injustice. Nothing that the U.S. entered World War II under the banner of antiracism and democracy abroad, she called for an end to “discrimination against workers and citizens because of class, color, creed, or sex” at home. Speaking for the AKA sorority, Ferebee concluded, “A nation-sweeping, all-out effort is imperative…[in order to] remove the inconsistencies between democratic theory and existing practice – to make democracy a reality in our Nation.22

Like Bethune, McConnell, and Staupers, Ferebee understood contraception as one of many determinants of reproductive self-determination, reproductive self-determination as one component of public health, and public health as one measure of genuine democracy. Oriented toward universal needs, these black women had their differences with white birth control advocates, who were less likely to embrace the kind of broad perspective that wove economic, racial, cultural, and gender factors into a structural analysis of the workings of the nation-state.

While Bethune, McConnell, Staupers, and Ferebee worked closely with the Division of Negro Service, they were also critical of it, occasionally publicly. In a widely reported speech to the annual meeting of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America in 1942, Ferebee delivered a mild reproach. After stressing the urgency of making contraception accessible to African Americans, she remarked that white birth control leaders were undermining the effort by failing to accept black allies as equals.23 In less scripted moments, these women were more blunt about racism in the movement. Staupers bristled at the paternalism of whites who assumed control over work intended to benefit blacks. She told Sanger pointedly, “[It’s time] you and your associates discontinue the practice of looking on us as children to be cared for and not to help decide how the caring should be done.24

The AKA “cotton-field clinics” received considerable press and attracted the attention of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who had recently acknowledged her support for birth control. With national policymakers in the early 1940s seriously contemplating proposals to guarantee health care for all Americans, Ferebee, Bethune, and other black club women lobbied Roosevelt to use her influence and encourage the federal government to look to the Mississippi project as a model for a comprehensive national health program. (Smith 1995, 164-65).

◊ ◊ ◊

« Previous: The Negro Project | Next: In the Hands of Midwives »