Over the early decades of the twentieth century, black women set the contours of a distinctive reproductive politics that encompassed the rights not to bear children, to bear children, and to rear children in safe, healthy conditions, as well as the right to sexual activity without sacrificing personal dignity or children’s needs. At a minimum, realizing those goals required freedom from racist stereotypes, sexual assault, and coerced sterilization, along with access to contraception and abortion, medical care, and economic security.

This agenda called for nothing less than social justice and begged questions that went to the heart of the U.S. as a nation-state. Was the U.S. a young nation evolving in fits and starts toward a more perfect union? Were the country’s institutions capable of reform sufficient to ensure actual liberty and equality for all, given political will and time enough? Or was the infrastructure so compromised by founding assumptions of race and sex hierarchy and the primacy of property—notions ingrained through centuries of ideology and practice—that only transformation to a new form of governance would suffice? Was the vision of justice a dream deferred or a delusion?

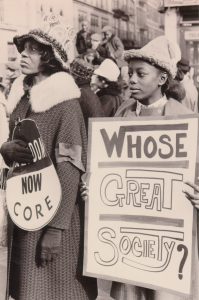

By 1960, with formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a new generation of black leaders was emerging to take up these questions (Holsaert et al. 2010). The terrain of reproductive politics was shifting rapidly. The birth control pill was about to go on the market, the Supreme Court was on the verge of decriminalizing contraception and declaring antimiscegenation laws unconstitutional, and movements for lesbian and gay rights and legal abortion were gaining strength. Passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act signaled changes in the race and gender balance of economic and political power, and contraception figured prominently in these realignments, which coincided with the federal government’s launch of a reform agenda of “Great Society” programs. One initiative was a “war on poverty,” which turned policymakers’ attention to the fertility of poor women and made family planning a national priority.

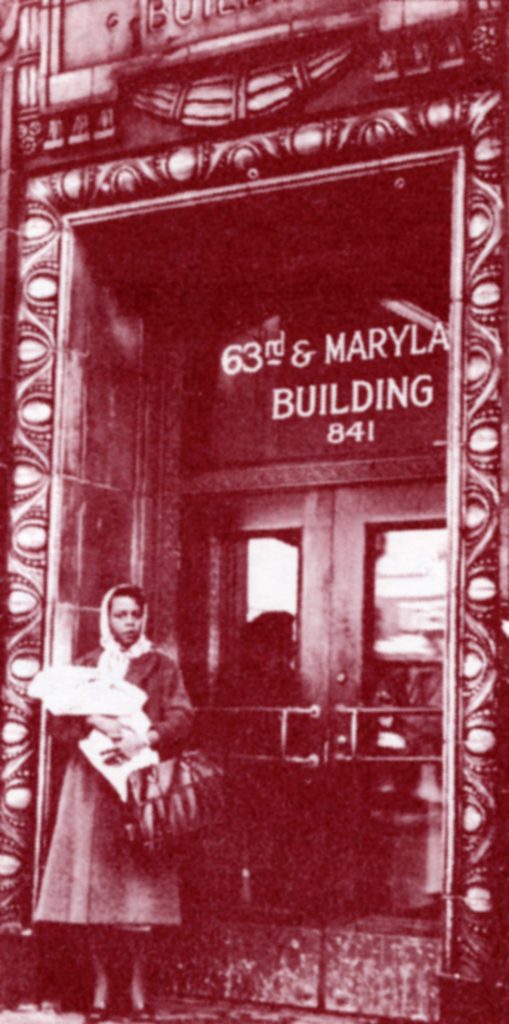

In this high-stakes moment, young black women built on the lessons of their mothers and grandmothers as they organized to place their own experiences of sexuality and reproduction on the agendas of expanding black freedom and women’s liberation movements. At times the older women stood by young activists on the front lines. Dorothy Ferebee, Dorothy Height, and others traveled to conflict sites in the South to bear witness and ensure that protesters detained for civil rights activism were not sexually molested by jail attendants or other hostile officials, as often happened. They also issued warnings born of long experience. They advocated that legalized birth control and abortion be available to black and white women on equal terms. At the same time, they cautioned that birth control and abortion, combined with sterilization, could be abused for purposes of population control if the government, in its attempt to reduce poverty, directed its force and funds toward reducing childbearing among poor women, thus limiting the growth and influence of communities of color, rather than toward unraveling the web of racial, economic, and gender pressures that rendered certain women poor.

With ever greater clarity, resolve, and impact in the years ahead, and soon in alliance with other women of color, the young African American activists would continue to refine political analyses and devise organizing strategies that flow from the sure, embodied knowledge that their struggle for sexual and reproductive self determination must be integral to any movement aspiring to make democracy real.32

◊ ◊ ◊