At the turn of the twentieth century, birth control was illegal in the United States. The Comstock Act of 1873 had labeled birth control obscene and banned distribution of contraceptive devices or information. By the 1910s, reformers were challenging the criminalization of birth control, and they achieved a minor victory when a New York court approved contraception for purposes of disease prevention.2

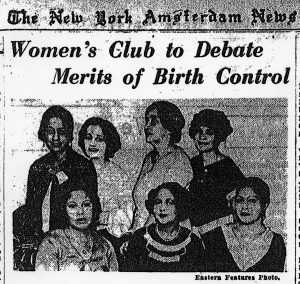

African American women routinely practiced traditional methods of preventing conception and terminating pregnancy, and in the early twentieth century they turned to pharmacies and mail-order houses for newer techniques. Some joined the movement for legalization. African American club women and male civic leaders sponsored public forums on the issue, advocated access to contraceptive knowledge, and promoted the creation of birth control services in their communities.3

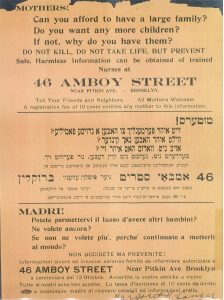

When Margaret Sanger emerged as a champion of birth control, African Americans sought her out. In 1919 in North Carolina, where Sanger was addressing a white audience, black women invited her to speak to their groups as well, which she did. (Sanger 1919). In New York City, after Sanger was arrested for publishing birth control literature and opening a birth control clinic in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn, the Harlem Women’s Political Association held lectures on the subject. Following Sanger’s opening of a second clinic, the Clinical Research Bureau in Manhattan, leaders of the Social Workers Club of Harlem and the Urban League urged her to establish a facility in their neighborhood. On February 1, 1930, the Harlem Branch of the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau opened its doors and soon served thousands of clients a year, approximately half of them African American.

An advisory board of prominent African American ministers, doctors, nurses, journalists, and social workers supported the Harlem Branch. The advisors cited abysmal living conditions in the black community as reason to take up the cause. Maternal and infant mortality rates in Harlem were twice those of whites in the city. Board member Dr. Louis Wright, who was medical secretary of the Harlem Hospital, pointed to “the appalling number of deaths” that came to his attention following illegal abortions as his motivation for ensuring that women had safe and effective means of separating sex from reproduction and regulating family size.4

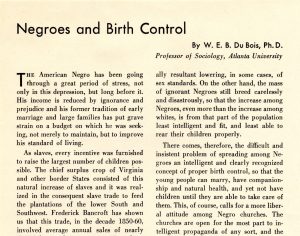

Opinions on birth control varied widely among African Americans. In his 1932 essay “Negroes and Birth Control,” the noted intellectual W. E. B. DuBois spoke to the array of considerations. DuBois, who had written as early as 1919 that a woman should have “the right of motherhood at her own discretion,” (DuBois 1920, 164-65) placed the issue in the historical context of slavery. He touched on the web of religious, cultural, and political concerns that surrounded matters of sex and reproduction and that stood in the way of African Americans’ ready acceptance of contraception, especially if it was dispensed by white reformers, government representatives, or medical personnel.

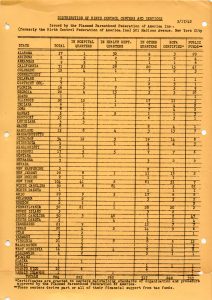

Although dispensing birth control remained illegal outside New York, local activists created hundreds of birth control clinics around the country in the 1920s and 1930s, especially after the 1936 Supreme Court One Package ruling, which modified the Comstock Act and allowed doctors to prescribe contraception for reasons other than disease prevention. The American Medical Association further spurred the spread of clinics with its endorsement of birth control the following year. By 1939, when advocacy groups merged to form the Birth Control Federation of America (BCFA), most states had at least one clinic.5

Most clinics, however, did not accept black clients. Those that did typically held segregated “Negro sessions” and maintained all-white staff who often treated blacks with condescension. At the Harlem Clinic, members of the African American Advisory Board were not given a full voice in setting policy, and it was only under pressure from the Board that the clinic eventually hired black staff. One black physician who observed the clinic closely remarked, “Again and again white people, competent in every other particular, get confused in the face of interracial endeavor.” As he explained it, “Lack of deep-seated interest usually accounts for this.”(quoted in McCann 1994, 135, 147-50).

Elsewhere black women’s groups were establishing services of their own. In Baltimore, Oklahoma City, Louisville, Richmond, Boston, Miami, Cincinnati, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and many other locales where their organizing was less well documented, African American women set up clinics in churches, community centers, and social workers’ homes. They also took contraceptive information to residents of housing settlements and pushed for the inclusion of birth control in maternal health and social welfare programs.

The black press aided the effort. Major newspapers, including the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier, the New York Amsterdam News, the San Francisco Spokesman, and the Afro-American, published editorials on birth control, carried ads for contraceptive devices, and spread news of the movement to a large national readership.

Still, advocates had barely begun to meet the need.

◊ ◊ ◊