At midcentury reports on African American women’s reproductive health were mixed. Overall, black women’s fertility rates dropped significantly between the late nineteenth century and World War II. To some degree the decline was a measure of success in pursuing birth control. Yet aggregate numbers glossed over deep inequities: more than a third of blacks had no access at all to health care or birth control. Similarly, although black rates of maternal and infant mortality improved over these decades, black mothers and newborns were still dying with much greater frequency than whites.

Future progress was far from certain. In plantation regions, white physicians not only continued to deny black women birth control; some routinely recommended regular sexual activity for girls as young as twelve and thirteen. (Orleck 2005, 30). In states, health officials were implementing drastic reductions in the ranks of midwives while channeling public funds into new but segregated and unequal services.

At the federal level, policymakers in the 1940s opted against a comprehensive national health program, and they proved unwilling to pit national authority against states’ rights for the sake of racial equality. Still, with the New Deal and desegregation of the defense industries and the military, the government had assumed some responsibility for the general welfare, and civil rights activists were upping the pressure for federal action toward integration.

Integration proved to be a problematic path. The U.S. Public Health Service took the position that racially specific programs were out of step with the times. The Service closed its Office of Negro Health and discontinued National Negro Health Week. When the formerly all-white American Nurses Association accepted blacks as members, Mabel Staupers achieved her long-sought goal, and the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses, which she led, disbanded in 1951. However, when racism persisted, African Americans eventually reestablished their own organization, the National Black Nurses’ Association.

African Americans fared little better with the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, where professional male leaders held sway over lay women activists. The PPFA also granted state affiliates freedom to set their own priorities, and most affiliates neglected race work. Florence Rose was furious with the leadership for its indifference toward the Division of Negro Service. Before she resigned in 1943, Rose raised a small sum to extend the Negro Project, and the PPFA did hire a series of field consultants to continue organizing among blacks. But in report after report, consultants vented exasperation. As Marie Schanks, an African American field worker, complained, not only did the PPFA assign race work to black staff who were paid less and expected to achieve more than their white coworkers; it also pressed black staff to tutor white colleagues in race relations.28

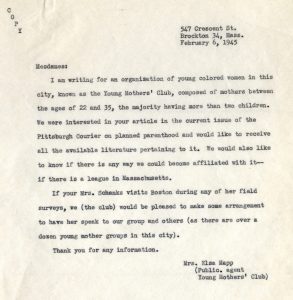

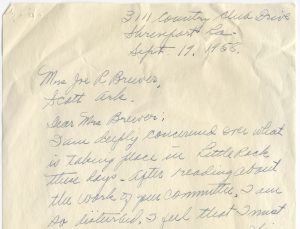

The wellspring of organizing for birth control and reproductive health lay in the needs and desires of women going about their daily lives. Elsa Mapp, a Boston area woman, read about Marie Schanks in the Pittsburgh Courier and sought her out on behalf of an organization of young black mothers in her neighborhood. Two weeks later Schanks met with the mothers at their local YWCA. She offered contraceptive information and briefed them on the uphill struggle to change state law and legalize birth control in Massachusetts.29

Mapp was among untold numbers of community-based women around the country who were persisting in the search for birth control and reproductive services for themselves and their daughters. Through grassroots efforts such as these, black women remained prime movers in sustaining health advocacy, and health advocacy, in turn, was seeding the broader civil rights struggle.

In the political climate of the cold war years, opponents of racial justice were quick to link health advocacy with civil rights activism and to denounce both as subversive. The powerful American Medical Association fueled the alarm by labeling proposals for a national health care system as “socialized medicine.”

The kind of suspicions Dorothy Ferebee aroused in Mississippi in the late 1930s and early 1940s — that AKA sorority women were outside agitators sowing discontent among impoverished black farm workers — grew into a national crusade against communism. Anticommunists fingered organizers like Ferebee who openly criticized health disparities as evidence of systemic race, class, and gender inequities that belied the nation’s claim to democracy. Health advocates lost jobs and more. In Congress in 1943, the House Committee on Un-American Activities branded Mary McLeod Bethune a communist, effectively indicting the entire black club movement and its comprehensive agenda. White-led women’s groups like the YWCA also came under suspicion for undertaking interracial work, favoring labor rights, promoting women’s equality and taking progressive positions on international issues.30

Racist sexual anxieties reverberated through the repression of dissent and reform. As the federal government moved toward outlawing segregation, white supremacists reacted with massive resistance that relied on familiar patterns of sexual intimidation and reproductive coercion. In 1954, when the Supreme Court issued its Brown v. Board of Education decision, declaring the Jim Crow system unconstitutional and mandating school desegregation, defenders of the status quo struck a raw nerve with dire warnings that integrated classrooms would effectively license interracial sex by giving predatory black boys access to innocent white girls. The resulting “mongrelization,” they claimed, would usher in social chaos and undermine the viability of the United States as they knew it.

In 1955, the brutal lynching of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old African American boy, for allegedly whistling at a white woman in Mississippi, followed by the highly publicized trial and acquittal of his accused murderers, put a generation of young blacks on notice that they presumed equality at their peril. When Till’s mother insisted on an open casket, declaring that she wanted the world to see the cruelty racism inflicted, the photo of her son’s mutilated corpse confronted a worldwide audience with a gruesome image of the anguish that attended black motherhood.

Popular culture at the time elevated white middle-class motherhood to a domestic ideal, pointing up the centrality of reproduction to the perpetuation of white supremacy. In its 1956 special issue, “The American Woman,” Life magazine featured a thirty-two-year-old mother of four. The “baby boom” she embodied reflected the nation’s reliance on affluent consumer households to ease the transition from defense to peacetime production and prevent the economy from relapsing into depression. She had dropped out of high school to marry at the age of sixteen and considered being a housewife her career, which included hosting frequent parties and serving as a community volunteer—all with the aid of a full-time maid.

Behind this celebration of private life was not only a domestic servant but a host of incentives and disincentives steering a generation of white women toward marriage and motherhood. For the housewife who embodied the ideal, alternatives were foreclosed by educational and occupational discrimination; by the illegality of contraception, abortion, and biracial marriage; and by psychological warnings against lesbianism and careers as symptoms of mental illness.

While pronatalist pressures expanded the white middle class, other policies cordoned off that family model to African Americans. Race discrimination denied most black men jobs that would support a dependent wife and children and consigned a large percentage of black women to either agricultural work or domestic service, where they cared for white women’s children. Often heads of household themselves, black mothers negotiated welfare policies that stigmatized them as sexually promiscuous and their children as unworthy of support. Welfare agents were known to grant poor white mothers public assistance on the grounds that their children needed them at home, but to reject black mothers’ claims for child support, reasoning that these women’s labor was needed in the fields. Many agents wielded their power over the public purse to police poor women’s behavior, withholding payments as a means of punishing challenges to segregation and enforcing compliance with its gendered regulations, such as the “man-in-the-house rule” that denied a mother benefits if she was in a sexual relationship with a man. Legislators in some southern states drafted laws to imprison or sterilize mothers on public assistance who gave birth to additional children, and in some places black mothers were more likely than whites to be subjected to sterilization as a condition of benefits (Solinger 2005, 131–49; Beardsley 1987, 296; Schoen).

Although anticommunism had chilling effects on progressive movements, black women continued to mobilize in ways large and small in the 1940s and 1950s. Hundreds of thousands fled the plantation region, migrating to safer settings where they formed supportive communities for themselves (Orleck 2005). Others kept up the fight through the National Council of Negro Women and interracial organizations such as the Congress of American Women or the YWCA. Dorothy Ferebee, in addition to holding leadership positions in both the NCNW and the YWCA, carried her concerns with her as she led the AKA into the newly formed American Council on Human Rights, a coalition of black sororities and fraternities committed to a multi-issue reform agenda.

For their part, radical black women took direct aim at the differential treatment of black and white mothers. Through their art, activism, and analysis, the playwright Lorraine Hansberry, the journalist Claudia Jones, the poet and actress Beulah Richardson (aka Beah Richards), and others involved in black left groups such as the Civil Rights Congress and Freedom newspaper, protested the caricature of “mammy” as a loyal and long-suffering servant content with caring for white women’s children while being unavailable to her own. The stereotype wished away tensions inherent in the inequities that bound black and white women together in the close quarters of households where servants were “like family” but emphatically not family at all.

Domestic workers poured those tensions into the streets of Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955. Thousands of domestic servants walked to work every day for a year rather than ride the city buses. A demonstration against racial and economic discrimination, the bus boycott was also a mass protest against the sexual indignities they confronted on public streets and buses and in private homes. Rosa Parks, who is often credited with sparking the boycott and portrayed as acting alone and spontaneously when she refused to give up her seat on the bus, was actually a seasoned organizer around sexual assault cases, and evidence suggests she may have had her own brush with harassment as a domestic worker (Garrow 1987; McGuire 2017).

As this collective resistance illustrated, each household in which a black woman labored to prop up a white woman’s status was a microcosm of a gender system that propped up race and class power. In her 1949 essay, “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman,” Communist Party leader Claudia Jones maintained that white men “have historically hidden behind the skirts of white women” by claiming they lynched black men as an act of chivalry, to protect the sexual purity and reproductive integrity of their wives and daughters. To the extent that white women embraced the homemaker role uncritically, Jones argued, they became standard-bearers of white supremacy, reinforcing the lies that underpinned it and excusing the violence white men committed in their name, including the “super exploitation” of black females as women, African Americans, and workers (Jones 1949; Weigand 2001, chap. 5).

Radical black women dissected the trope of white womanhood as a protection racket. What white women protected by providing cover to their fathers, husbands, and sons was a social order held together in a web of male dominance, white supremacy, and capitalist rule. In the bargain, white women traded away their own economic independence and sexual freedom, including the option of consensual relations with non-white men. Therefore white women too had a stake in unraveling the web and promoting social justice.

The U.S. government deported Jones for her ideas. Nonetheless the importance of black women’s control of their bodies was gradually taking hold within black movement culture, which had previously emphasized violence against men. Around the country local leaders formed committees not only to rally around black men falsely accused of raping white women but also to support black female victims of sexual assault who mustered the courage to file charges against white assailants. Black press coverage of individual incidents grew into a compelling body of evidence, and national civil rights organizations began categorizing these as “sex crimes”(McGuire 2010).

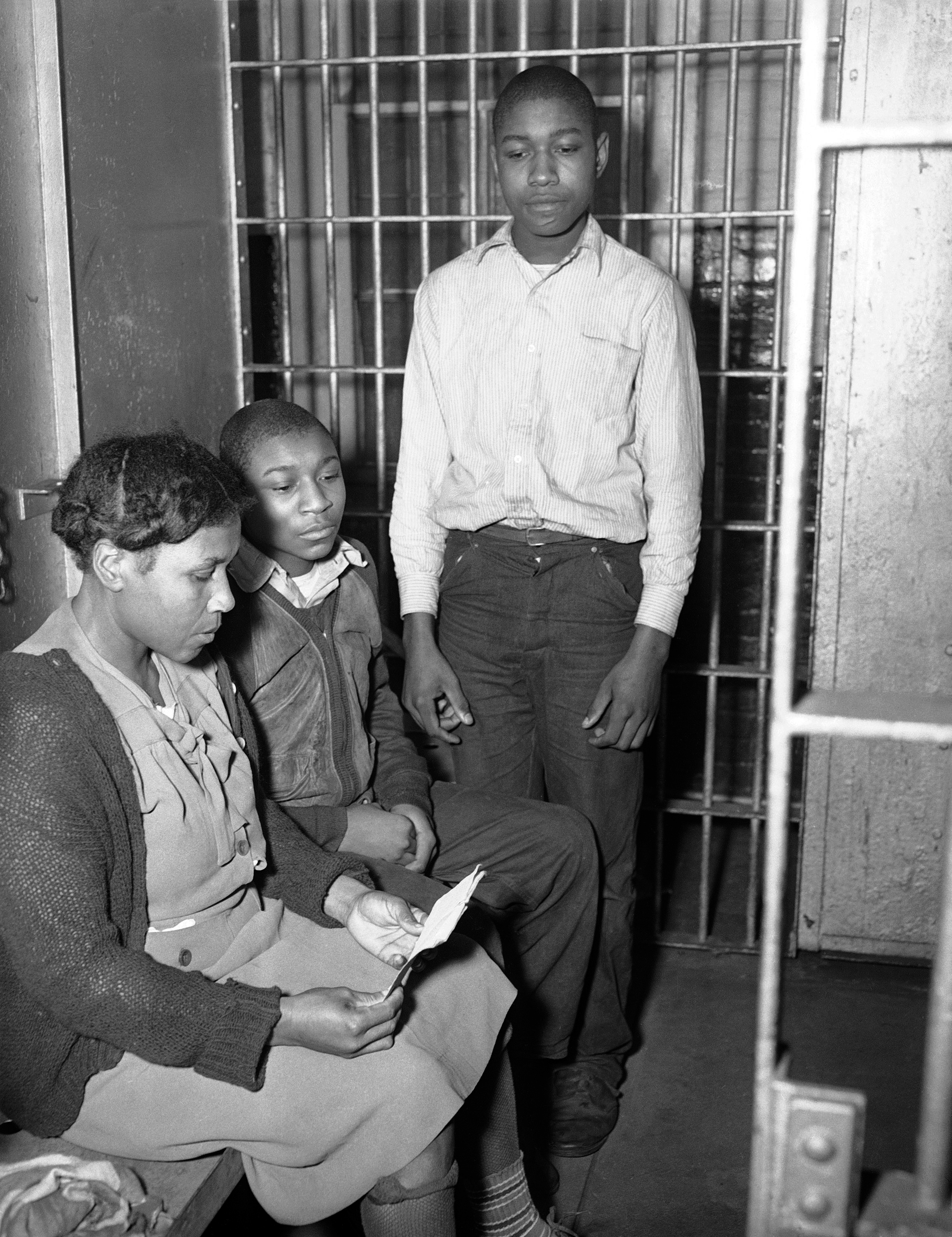

The case of Rosa Lee Ingram came to symbolize the plight of black mothers entangled in the web of sexism, poverty, and racism. A sharecropper and recently widowed mother of fourteen children, Ingram and two sons were sentenced to execution in the 1947 death of a white male neighbor with whom they had run-ins and who, Ingram said, sexually harassed her repeatedly. In a decade-long national campaign to free the three, activists stressed Ingram’s family role, sending thousands of appeals to President Truman on Mother’s Day.

They also championed her right to self-defense. In Beulah Richardson’s poem “The Revolt of Rosa Lee Ingram,” Ingram voiced the bold, disruptive claim that drove black women’s activism: “My body belongs to me.” Radicals elaborated that claim into a critique of the nation itself: it was at best “a strange democracy” that could abide unchecked killings of black men on trumped-up charges of threatening white women and families while turning a blind eye to white men’s actual violation of black women, and, at the same time, condemn a black woman to death for defending her dignity and her children.

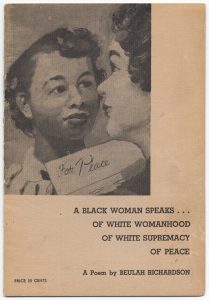

Radicals laid those hypocrisies on the nation’s doorstep. Inspired by another of Richardson’s poems, “A Black Woman Speaks . . . of White Womanhood, of White Supremacy, of Peace,” they mobilized as Sojourners for Truth and Justice. Summoning women to “dry your tears and speak your mind” and “demand the death of Jim Crow,” Sojourners staged a 1951 protest at the U.S. Justice Department. Citing the Ingrams and a spate of recent lynchings, they presented their personal testimonies as wives, mothers, and victims as proof of the government’s complicity in “legal lynching” and other forms of racial hatred.

African American women took their grievances into the international arena. Just as world tensions were shifting from Europe to Asia, Africa, and Latin America, making cold war politics increasingly racialized, black women pushed sexual and reproductive oppression to the center of the struggle against white supremacy. Further, they likened the struggle in the U.S. to anticolonial movements of peoples in the Global South who were claiming independence after centuries of subordination to white European imperial powers. Invoking criteria newly established by the United Nations, they charged the U.S. government with “domestic genocide” for condoning habitual assaults against African Americans. By soliciting international support for the Ingrams and others, African American women invited the community of nations to hold this “strange democracy” to the standards of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights.31 The pressure they generated contributed to the eventual release of the Ingrams on parole in 1959.

◊ ◊ ◊

« Previous: In the Hands of Midwives | Next: Whose Great Society? »