Legal segregation, racist beliefs, and dire poverty blocked African Americans’ access to health care, and the economic depression of the 1930s made a bad situation worse. At the end of the decade Time magazine pronounced poor health among blacks to be the nation’s most pressing health problem. (“Negro Health” 1940, 43). The well-being of mothers and children was a stark measure of this inequality. With diseases such as tuberculosis and syphilis going untreated, the risks associated with pregnancy and childbirth increased. African American rates of maternal and infant mortality, which already dwarfed those of whites, rose even higher.6

National attention turned to the South, where a large majority of African Americans lived. Southern cities, counties, and states were beginning to build public health systems, and some of them dispensed birth control, but they typically served only poor whites. Passage of New Deal health and welfare reforms, notably the 1935 Social Security Act and its provision for Aid to Dependent Children, raised hopes of federal action.

Birth control organizations dispatched field representatives to the South in the late 1930s to assess the practicality of distributing contraceptive foam powder to poor women who lacked basic services such as running water. They found black women already organizing and stirring up interest. One field worker, Hazel Moore, told of a black mother who arrived at the dispensing site with her five children in tow. They had walked “a good piece” to get there, the mother reported. Asked if she could have left her children in the care of a neighbor, the mother replied, “Yes ma’m, but dis here is my evidence so I can get dat control.”

If black women’s desire to limit pregnancies was evident, so were the obstacles. In one instance, several women came back to a dispensing site, cans of foam powder in hand. As Moore recounted it, the women explained that the evangelical minister of their Sanctified Church had disapproved and directed them to return the powder and profess their faith that “de Lord will take care of me and my children.7

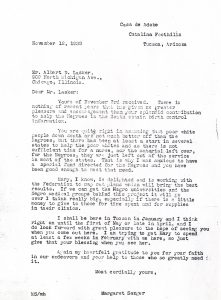

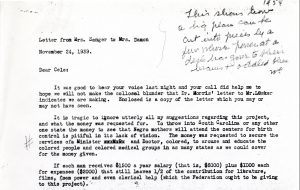

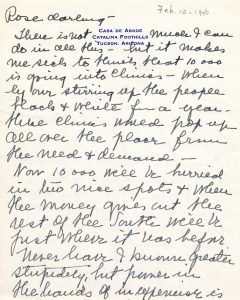

In the field projects birth control organizations were running and in the national concern for black health and poverty, Margaret Sanger saw an opportunity for a concerted effort in the South. Although Sanger was far removed from daily operations of the BCFA by this time — she had been sidelined to a position as honorary chair of the board and was living in Arizona — she continued to collaborate with Florence Rose, her longtime personal secretary, who had great enthusiasm for the venture. Rose remained at BCFA and spearheaded the initiative that became known as the Negro Project.

In spelling out the rationale for a project that focused solely on African Americans, Rose and Sanger navigated a dense maze of political realities, bureaucratic constraints, demographic concerns, pseudo-scientific claims, cultural and religious beliefs, and racial and sexual attitudes. By and large, in the midst of economic crisis and world war, the appeal was to public health and general welfare, and these were malleable concepts.8

Some advocates were advancing eugenic arguments for birth control to prevent overpopulation by an underclass. Sanger accepted some eugenic beliefs; in keeping with prevailing views, notably the 1927 Buck v. Bell ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court, which endorsed the sterilization of institutionalized individuals considered to be genetically flawed, she favored restricting reproduction by those with hereditary deficits. At the same time, she criticized as “cradle competition” any practices intended to control population by race, class or religion, whether by pressuring women in some groups to bear fewer children or by persuading others to bear more. (Sanger 1922).

In the case of the Negro Project, Sanger gave an occasional nod to women’s rights. She frequently cited the high rate of abortion as a measure of African American women’s desire to avoid pregnancy and the risks they incurred to do so. Commenting on newspaper coverage of the project, she remarked that the headlines were more than news; they were “lifelines to the mothers we are dedicated to free.9

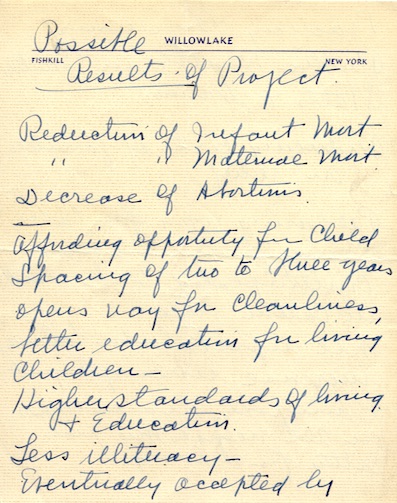

Sanger and Rose saw promise in birth control as a community strategy of African American survival and progress. In their proposal for funding from philanthropist Albert Lasker, they touted the project as “a unique experiment in the field of race-building, as well as in the field of humanitarian service for a race that has been subjected to discrimination, hardship and segregation.” They made the case this way:

Birth Control, per se, cannot correct the economic conditions that result in bad housing, overcrowding, poor hygiene, malnutrition, and neglected sanitation in which Negroes are forced to live through special social and economic pressure. But Birth Control can reduce the attendant loss of life, health, and happiness that spring from these conditions in the form of excessive infant and maternal mortality among negro mothers, high morbidity rates, tuberculosis, syphilis, mental disease, epilepsy, rheumatism, heart disease, illiteracy, child-labor, ignorance and despair.10

Lasker agreed to fund the project, explaining to Sanger, “I do not see how we can have the secure democracy for which our men are fighting and dying until we find a place of security and dignity for the Negro in our national life. If one minority is degraded, we are all affected, for we all belong to some minority.11

In addition to spelling out different motivations and objectives, proponents debated competing strategies for implementing the work. Sanger was mindful of lessons from the Harlem Clinic, including critiques from the advisory board about distrust among blacks. She argued strenuously for a full year of “education agitation” before clinical services would be introduced. She insisted that African Americans were best suited to do that groundwork, which would involve dispelling fears of genocidal intent and misconceptions that confused birth control with abortion. As she saw it, African American spokespersons stood the best chance of getting a hearing at the grassroots and convincing local leaders, especially ministers, to accept the benefits of contraception, or at least cease denouncing it.12 Ministers were community gatekeepers, and their backing had proved essential to popular participation in earlier health campaigns for immunization and screening.

Sanger also considered it a plus that ministers were men. After a quarter century on the front lines of the movement, she was keenly aware of male medical practitioners’ bias against women, whether health professionals or organizers. She also knew that while men opposed granting women the autonomy to prevent pregnancy, they were averse to using condoms. Rather than attempt to change men’s minds about condoms – and thereby cede men the balance of power in sexual relations — Sanger preferred a contraceptive method that enhanced women’s say. A husband might be more accepting of his wife’s use of birth control, she mused, and a father might even educate his son to the practice, if the messenger was not only a minister but a male.13

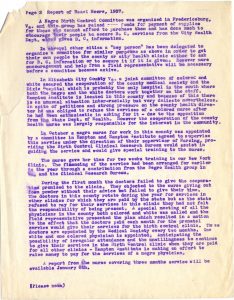

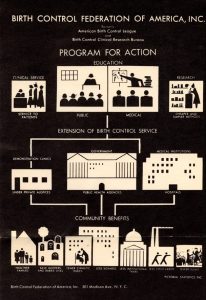

Sanger and Rose did not succeed in winning the leaders of the new Birth Control Federation of America to their educational approach. The leaders favored a medical approach that would incorporate contraceptive services for blacks directly into existing white-run health programs. Southern officials and medical practitioners agreed, as did Lasker, who pledged $20,000 to the project. With funding secured and plans outlined, the BCFA created a Division of Negro Service to oversee the setup and operation of demonstration clinics in rural South Carolina and urban Nashville, Tennessee. The clinics ran from 1940 to 1942.

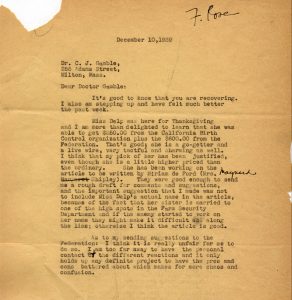

Even as the clinics began operations, Sanger and Rose remained convinced that “the medical way” was wrongheaded, and they went ahead with their prefered community-oriented educational approach. With Sanger’s support and ample fervor of her own, Rose solicited endorsements from major black organizations and medical groups. She also mounted a nationwide outreach campaign to put informational material in the hands of public health nurses, social workers, home demonstration agents, teachers, welfare workers and others who might influence public opinion or come in direct contact with women who lacked access to birth control.

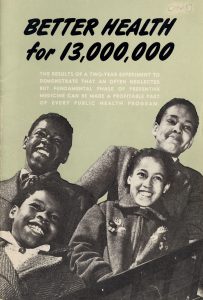

In 1942, as the Negro Project was coming to an end, the Birth Control Federation of America took a new name, Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA). Planned Parenthood issued Better Health for 13,000,000 as a final report on the initiative.

In the end, the Negro Project had less impact than published accounts might suggest. It proved to be neither the genocidal plot that wary observers feared nor the breakthrough for women’s autonomy and racial progress that optimistic promoters envisioned. At the demonstration clinics, the number of women seeking services fell far short of what planners had hoped, and the sites yielded no lasting model for serving poor women. Within BCFA, Sanger and Rose failed to drum up much enthusiasm for the work. They raised the start-up funds themselves, and no other donor stepped forward to match Lasker’s investment and encourage Planned Parenthood to continue the project.

Rose and Sanger’s educational campaign may have had the greater effect. Not only did the community organizing effort spread factual information and positive arguments about birth control, but it engaged black women leaders who had the personal determination, social connections, and political vision to sustain the drive for women’s sexual and reproductive rights over the long term.

◊ ◊ ◊

« Previous: Creating Community Clinics | Next: Leading Voices »