Amidst the cacophony of all that I am reading, hearing, and taking in response to the verdict in the Ferguson Grand Jury deliberation,—which I am, like many of us, just barely beginning to sort through—I have little, if anything, different or new to say.

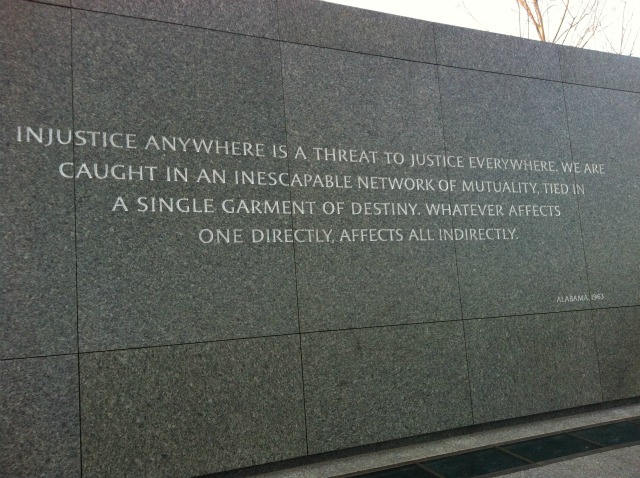

I do keep thinking about this quote form the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr., ” We’re caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly…” I have been wondering, what does it mean to be affected “directly” verses indirectly,” and how do we call into question these very notions, surrendering to this “inescapable network of mutuality” which most of us don’t fully experience ourselves as part of, most of the time?

Our criminal justice system in the United States is broken, or perhaps better said; flawed at its core. That it protects some and not others is abundantly clear.If you are a black or brown person living in the United States, particularly if you are African-American you are likely to be affected directly by it; while if you are white or pass as white, you are more likely to be affected indirectly.

We need to reckon with, face that horrifying reality head on, in order to really see the truth. To live as a black or brown-skinned person in the United States is to experience life differently than to experience life as a white skinned person. It is the responsibility of every person who understands and experience themselves as white to acknowledge, excavate, and deeply mine that reality. Things will not change until white people recognize the unearned advantages of our everyday life which make things like sending our children outside to play in public spaces different experiences than they are for black or brown people.

Yet there is a paradox, for at the very same time, if we take seriously King’s articulation.

What happened to Michael Brown’s family happened to all of us…At this moment in time we have to live in the terrifying, narrow but endlessly deep cavern of space in between these two realities. Some are effected “directly” and some are effected ‘indirectly.” Yet, at the same time If we live in the United States, whether or not we are citizens, we are part of this single garment of destiny, what effects one, effects all.

So I think we have to find a way to live, work, and organize, find a way to inhabit that liminal space where both realities are true, as if our lives depended on it. Because actually, they do.

Amidst all I am hearing and reading, one of the many things that struck me today was the reading at the 12:00 Vigil today, Wednesday November 26th, on the Smith College campus by a Smith American Studies professor Micheal Thurston. It galvanized me for a moment and brought me some small measure of hope and I am sharing it here with his permission:

You have heard, beginning around 9:30 last night, and you will hear in the coming days, that we need to be calm, that we must cultivate quiet and engage civilly in deliberation and debate. I am here to say that I respectfully disagree. I am here to say “cry out.” And I am here to cry out too. There will be time for calm and quiet, for deliberation and debate, but this, I think, is not that time. To move too quickly toward those is to skip over an important moment, the moment of reckoning with a wound, the moment of acknowledging our pain in this episode, in this woeful history, of wounding. There will be time to move past anger and anguish, but only once we have fully inhabited anger and anguish, and so I am here to raise my voice for the raising of our voices.

We are in and of an educational community, an institution of learning, and the history we preserve, the practices we cultivate, make room not only for the eloquence of argument but also for the inarticulate howl of pain, of grief, of rage. There is, early in the history of western literature, the figure of Philoctetes, wounded in war and abandoned by his mates, left only to howl, as Sophocles writes it, “Ai, Ai, Ai!” That syllable is also the one cried out by Apollo when his beloved Hyacinthus dies, and it is written in the flower the god crafts in his lover’s memory. There is in these stories transformation of pain into civic virtue, into emblems of love and poetry, but there is, before the transformation, the full and open and vulnerable and human cry, and we are taught by our traditions that we must hear that cry, that we must take in and even, sometimes, join that cry, that there is value in this recognition of the wound, and that, for progress to occur, we must meet and cry together in the space of the wound. And so we cry out, raising our voices with the voices of families and friends who cry out “Why?” With the voices of those who cry out “No!” With the voices of all who cry out, simply, inarticulately, wounded and angry and grieving.

So I invite us now, to cry out, inarticulately. Be with me for a moment in this place of not much new to say. Perhaps the thread that weaves together that garment of destiny that King talks about emerges from here—between silence and words, between despair and hope, in a cavern between two simultaneously true realities that are constitutive of life in the United States.

Posted by Matilda Rose Cantwell, Interfaith Fellow