After the opening remarks on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the American Friends Service Committee hosted two panel discussions on racial justice. I was proud to moderate the first panel of student fellows for the Justice, Identity, and Social Change Initiative of the CRSL described in the previous blog.Before asking the student panelists the questions, I made some opening remarks.

Organizers of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement and Michael Eric Dyson, author of I May Not Get Here With You, shed light on the ways in which MLK day holiday has been “domesticated” and “whitewashed” King himself—his deeply radical nature made more conventional in order to fit neatly into a society that has been mistakenly viewed as post-racial. BLM organizers call to reclaim MLK Day:

Dr. King was a part of a larger movement that shaped our imagination for what change looks like in this country. From trans women of color at Stonewall who resisted police violence to sanitation workers in Memphis demanding basic dignity, the movement was built on a bold vision that was radical, principled, and uncompromising.

Another piece of King’s legacy that has been diluted in the mainstream was his reliance on religion, the depth of his spiritual grappling and commitment, and the extent to which the Civil Rights movement of the 60s was undergirded by an interfaith ethos.

Why does this matter? It matters because the heart of every religious tradition—disentangled from its enmeshment with politics and empire—is the commitment to radical social change. It’s the subversion of the world as we know it, the overthrow of the “powers that be” (a phrase coined by Walter Wink). If our consciences are truly liberated, then our societies are too. This is the “faith” in the interfaith of the Civil Rights movement that embraced philosophies of Hinduisms, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

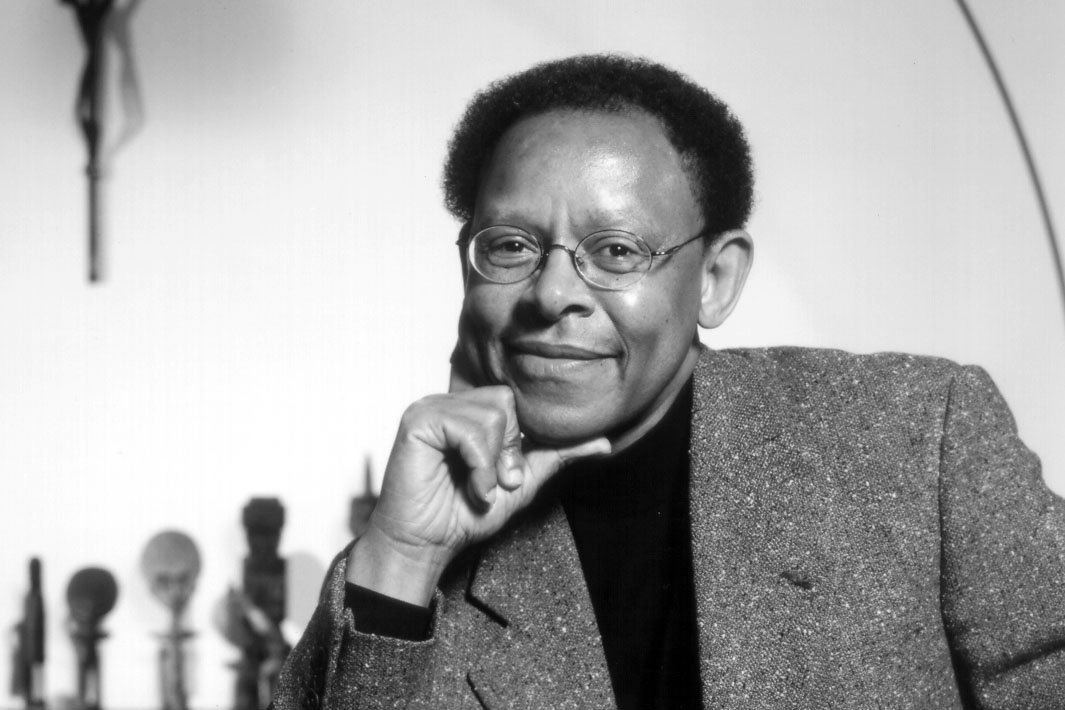

If we domesticate King, we domesticate his Jesus. And if we do this, we miss the opportunity to reclaim his legacy. James Cone, founder of black liberation theology, says that Christianity is nothing if it is not about the liberation of black people.

He says anti-blackness is the original sin of our society. All lives can only matter when black lives matter. This is what Jesus would have said in our time. So we can only claim Christianity when we put those who have been violently marginalized at the very center of our concern.

Thus the creation of exclusive black spaces—such as those at Yale and Missouri University—have deep and authentic spiritual theological integrity. While they are not always unified or organized political movements, students’ struggles are endeavors deeply rooted in the radicalism of Malcolm X and the liberation theology of James Cone. They are the first way forward in the movement for black lives.

Hence I draw our attention to the organization of student activism on college campuses, our own Smith campus in particular, where social identity is at its core. Those that are confused may ask: Why is social identity so important? Where do we situate ourselves in the fight for justice? Why does it matter how I speak, or what words I use, as a white person? Aren’t the most universal values the inherent worth and dignity of all human beings?

According the liberation theology that formed me as a person of faith, and according to the insights and wisdom of those young people living it—yes, and no. The inherent worth and dignity of all humans can only be upheld when the inherent worth and dignity of those who have been oppressed is paramount.

In a minute our student panelists will talk about their experience and bring to light their thoughts about how and why an institution of higher education, if it is to be about all lives, must be about some lives, first. I hope it will lead us to give deeper thought to what we think it means to be a secular institution, where diversity, the free exchange of ideas and civil discourse are the highest good. How free can a free exchange of ideas be if those expressing the ideas are not themselves on equal ground? This is a question we must consider.

The students will engage in discussion that will help us understand, I hope, why for them, language, history, social identity matters. They will encourage us, as I hope we have encouraged them, to work for common understanding, they may chide us gently, but the Civil Rights movement would not be what it was without the voices of the young people, without those who help us move to be bold, visionary and uncompromising. The philosophy of active nonviolence of king was indeed just that—uncompromising, it refused to succumb to violence, it refused to stop listening in the face of judgment and misunderstanding. And even the generation gap.

While denominationalism is on the decline and religiously these students are part of the “none’s”—students are no less spiritual. At Smith’s Center for Religious and Spiritual Life, we seek to pair contemplative practice with radical action, for we believe that by doing so we are situating ourselves in a worthy tradition whose values are not only important, but urgent. Pierre de Chardin said “We are not human beings having a spiritual experience. We are spiritual beings having a human experience.” It is of upmost importance that we regard the students’ activism as expressions of their deep spiritual experiences, and follow their lead where we are inspired and challenged to do so.