Dr. Lihi Ben Shitrit, Assistant Professor of International Affairs at the University of Georgia, presented a chapter summary and lecture drawn from her 2015 book “Righteous Transgressions: Women’s Activism on the Israeli and Palestinian Religious Right.” Dr. Shitrit travelled throughout the West Bank, engaging in interviews and participant-observation studies with four groups on the religious right: Palestinian Hamas, Jewish Settlers in the West Bank, ultra-Orthodox Shas, and the Islamic Movement in Israel. The contents of Dr. Shitrit’s book examine the apparent anomaly of women’s advocacy in socially conservative religious-political movements.

“We need to shift our inquiry from why, to how, do women support socially-conservative agendas,” Shitrit said; some attendees nodded in approval, others looked inquisitive. Women in these movements are often framed as victims, unwillingly subservient to a structure they would oppose, if given the freedom. Shitrit picked apart the problematic nature of this Western Feminist conception throughout her lecture.

Shitrit began by challenging the Western scholastic failure to analyze the role of women in these movements as actors, rather than subjects. While there are women who hold roles in social and political representation, the roles of many women are sequestered to the private sphere. To regard the private sphere as separate from society is a failure of Western scholarship; in reality, it is a critical facet of social structure and function in much of the Middle East.

Shitrit presented on three forms of women’s activism: complementarian, public protest, and formal representation. Complementarian activism is rarely considered activism at all. Motherhood, homemaking, modest dress and behavior, and working to spread religiosity amongst other women are considered complementarian action: “feminine” activity which takes place in mainly “segmented” spheres. Shitrit affirms that complementarian activism is no less valuable or powerful because it appears to comply with a patriarchal structure. These women navigate the structure they exist within to inspire social change.

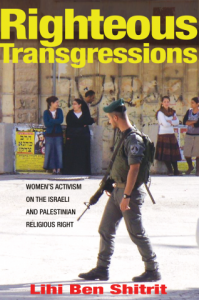

Shitrit’s book Righteous

Transgressions (photo courtesy

of Princeton University Press)

Within complementarian action, women have access to other women: they are able to provide education and religious training for children, develop networks of trust and support, and participate in women’s organizations. Each of these efforts is underpinned with the intention of reforming society. Bedouin women have gained authority through religious-political activism. These movements have helped prevent early marriages and other traditions Bedouin women deemed oppressive by arguing that the origins of these practices are in Bedouin culture, not Islam. In the West Bank, settlements are made into communities by the women who reside there. Without women and the work they contribute, says Shitrit, these settlements would simply be military outposts.

Shitrit’s presentation shifted the audience to see women’s activism from a new lens, one that is not obstructed or warped by a Westernized interpretation of gender progression. It is too easy to dismiss the work of women in the private sphere, because a common conception of activism is revolution, protest, and blatant action. Shitrit has shown us that the more subliminal work of women on the religious right is no less valuable or powerful.