What Would Mrs. Biddle Serve?: Food as Social Currency in Gilded Age Philadelphia

by Emma Tierney ’22

Cookbooks exemplify the ideals of a society–what an authority thinks people should eat, what their society values. Print cookbooks are generally aspirational, while handwritten cookbooks give an account of what people actually ate, giving us a glimpse of their real lives. In her handwritten recipe book, Mrs. George W. Biddle gives an honest view of the values of high-society women in the 19th century through the recipes she includes. Mrs. Biddle used recipes as social currency, trading with other women and recording ones that elevated the status of her family.

Background

Maria Coxe McMurtie (1818-1901) married the head of the prominent Biddle family of Philadelphia to become Mrs. George W. Biddle. George Biddle (1818-1897), her husband, was a lawyer who served several Presidential counsel appointments. The family had a long history of military service, including a Revolutionary War soldier and Civil War Colonel (Dodge). With large amounts of land, the family had significant generational wealth. Combined with their historical significance, their wealth allowed the family to move among the top circles of society, which enabled Maria to be a society hostess (Biddle).

Maria Coxe McMurtie (1818-1901) married the head of the prominent Biddle family of Philadelphia to become Mrs. George W. Biddle. George Biddle (1818-1897), her husband, was a lawyer who served several Presidential counsel appointments. The family had a long history of military service, including a Revolutionary War soldier and Civil War Colonel (Dodge). With large amounts of land, the family had significant generational wealth. Combined with their historical significance, their wealth allowed the family to move among the top circles of society, which enabled Maria to be a society hostess (Biddle).

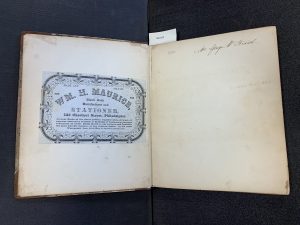

The physical book provides useful information about its owner. The upper pastedown shows that the book was purchased from Wm. H. Maurice, Stationer, who occupied 123 Chestnut Street between 1853 and 1856, when the book must have been bought. The shop was situated between the Society Hill and Old City neighborhoods, which, at the time, were very affluent and desirable areas. From this, we know that the Biddle family had means, but also frequented socially fashionable places where their presence would be noticed by their peers (Biddle).

The Cookbook

The most notable feature of the cookbook is the type of recipes included. The recipes are best described  as decorative; they serve the same function as the silverware being used and the painting on the wall. The purpose is to impress the guest with the amount of money the host is willing to spend on a meal, and to make them wonder: “If they have this much money for food, how rich are they?” The “entree” recipes are all comprised of fine cuts of meat. Due to the lack of electricity, meat spoiled very quickly, making it extremely expensive in the mid 19th Century (United States). Serving meat was a socially acceptable way of flaunting wealth, or, conversely, creating the illusion of wealth. Therefore, serving recipes such as “Veal Cutlets,” “Calf’s Head,” “Bouillis Beef,” and “Mutton Chops” impressed the company, heightening the reputation of the Biddles among their friends and peers. The quantities of meat are particularly impressive with “Bouillis Beef” using a whole brisket, and a whole veal shoulder and head used in various other recipes (Biddle).

as decorative; they serve the same function as the silverware being used and the painting on the wall. The purpose is to impress the guest with the amount of money the host is willing to spend on a meal, and to make them wonder: “If they have this much money for food, how rich are they?” The “entree” recipes are all comprised of fine cuts of meat. Due to the lack of electricity, meat spoiled very quickly, making it extremely expensive in the mid 19th Century (United States). Serving meat was a socially acceptable way of flaunting wealth, or, conversely, creating the illusion of wealth. Therefore, serving recipes such as “Veal Cutlets,” “Calf’s Head,” “Bouillis Beef,” and “Mutton Chops” impressed the company, heightening the reputation of the Biddles among their friends and peers. The quantities of meat are particularly impressive with “Bouillis Beef” using a whole brisket, and a whole veal shoulder and head used in various other recipes (Biddle).

The names of the recipes also served a decorative and self-aggrandizing purpose, while allowing the family to stay humbly separated, as the butler would announce the dish. Most notably, the “Federal Cake” casually reminds the guests of the family’s heritage—Clement Biddle’s significant role in the Revolutionary War— while showing their patriotism through devotion to American identity, and hinting at Mr. Biddle’s role as a counsel to the President. The book also contains five recipes for turtle soup or mock turtle soup (Calf’s Head Soup), a dish with a strong tradition in Philadelphia (Schweitzer). Serving turtle soup, especially to out of town guests, connects the Biddles with a culturally significant dish, showing their prestige and influence as one of the most prominent families in Philadelphia. While, contrarily, “Indian cake” and “Spanish buns” make the family appear cultured and well traveled, which were very desirable traits as young upper class Americans were expected to go on their Grand Tour (Biddle) (Sorabella).

The names of the recipes also served a decorative and self-aggrandizing purpose, while allowing the family to stay humbly separated, as the butler would announce the dish. Most notably, the “Federal Cake” casually reminds the guests of the family’s heritage—Clement Biddle’s significant role in the Revolutionary War— while showing their patriotism through devotion to American identity, and hinting at Mr. Biddle’s role as a counsel to the President. The book also contains five recipes for turtle soup or mock turtle soup (Calf’s Head Soup), a dish with a strong tradition in Philadelphia (Schweitzer). Serving turtle soup, especially to out of town guests, connects the Biddles with a culturally significant dish, showing their prestige and influence as one of the most prominent families in Philadelphia. While, contrarily, “Indian cake” and “Spanish buns” make the family appear cultured and well traveled, which were very desirable traits as young upper class Americans were expected to go on their Grand Tour (Biddle) (Sorabella).

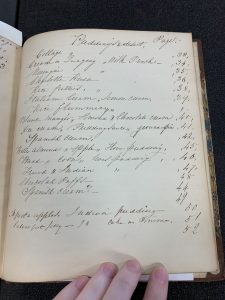

The recent creation of afternoon tea facilitated an occasion during which upper class women socialized and was often used for self and family promotion (Whitehead). This ritual explains both the prevalence of sweets in the cookbook and the inclusion of recipes attributed to other women. The table of contents highlights the abundance of recipes for sweets and baked goods. Presumably, Mrs. Biddle created the categories, putting savory recipes into broad and sparsely populated categories like “soups” and “meats,” while sweet categories were made very specific, such as “hot cakes” and “puddings,” which have the highest concentration of recipes. The first recipe in the book, “Soft Gingerbread,” is followed by many more desserts, which suggests that Mrs. Biddle felt they were most important to record (Biddle). They would have been important because sweets and finger sandwiches were served at afternoon tea. Serving delicious sweets would have improved her reputation as a society hostess, which in turn would heighten the prestige of her entire family.

While Mrs. Biddle hosted afternoon tea, she also attended those held by her peers who tried to accomplish the same goal of impressing their guests. This reciprocated social event led to the sharing of recipes which made their way into the recipe book of Mrs. Biddle. An “Indian Pudding” recipe is attributed to Mrs. B.B., meringue was borrowed from Mrs. Jacobs, and her mother-in-law contributed with “Mrs. Clement Biddle’s Black Cake” (Biddle). The trading of recipes was the most physical representation of social currency, with the woman giving out recipes receiving social accolade.

Interestingly, the recipes—even the shared ones—assume a high level of culinary knowledge, ranging from techniques to specificity of ingredients. Due to their socioeconomic status, it can be assumed the Biddle family had servants and cooks, who would have the necessary culinary knowledge. In addition, the recipes included in the book are not ones that would be made everyday, showing that Mrs. Biddle left the day-to-day meals up to the cook, while taking part in the collection of recipes for guests and special occasions, when she would have had higher expectations, and, thus, wanted to be involved in the planning process (Biddle). The recording also assumes a significance of the recipes, whether it be sentimentality or popularity among guests. Presumably, Mrs. Biddle wanted these—her favorite—recipes written down in the event that she got a new cook.

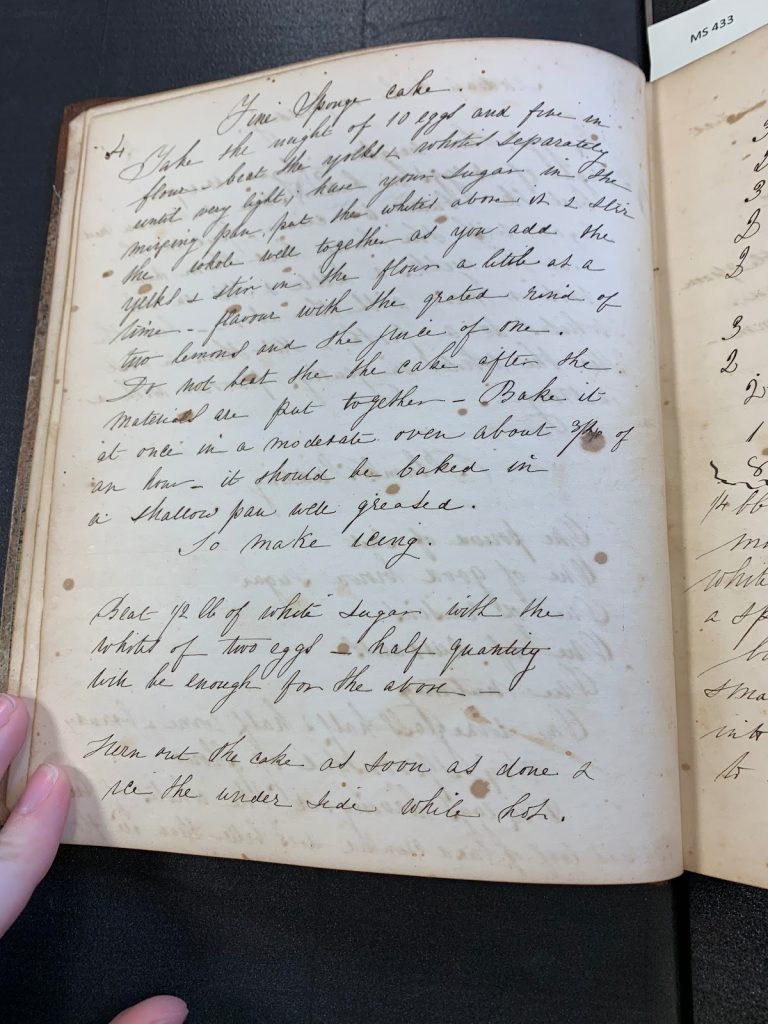

“Fine Sponge cake:” Creating a Recipe

When reading the recipes it becomes apparent that they are meant for someone with a background in cooking. This is reasonable, given the previously stated assumption that Mrs. Biddle used the book to record her favorite recipes to pass along to new cook. As an avid baker, lover of sweets and history nerd, I decided to recreate the “Fine Sponge cake” recipe. This page particularly interested me because it has food stains, meaning it was probably a popular dessert. The recipe also calls for a dozen eggs, and I was very curious as to how a recipe could use that many and not taste like scrambled eggs (Biddle).

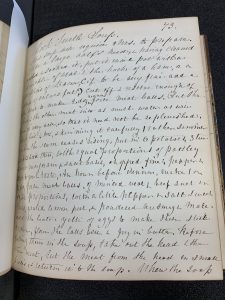

The first step was transcribing the recipe from the handwritten text. Some words were unable to be deciphered due to the penmanship, which often left t’s uncrossed and occasionally misspelled words. Question marks indicate an unknown word, and words in parenthesis next to the question marks indicate unconfirmed possibilities. The transcription of the page:

Fine Sponge Cake

Take the weight of 10 eggs and five (oz/in)??? Flour. Beat the yolks + whites separately until very light; have your sugar in the ???? pan, pat the whites above in 2 stir the ???? well together as you add the yolks + stir in the flour a little as a time. Flavour with the grated rind of two lemons and the juice of one. Do not beat the cake after the materials are put together. Bake it at once in a moderate oven about 3/4 of an hour. It should be baked in a shallow pan well greased.

To make the icing

Beat ½ pound of white sugar with the whites of two eggs. Half quantity which be enough for the above.

Take out the cake as soon as done to ice the under side while hot

Getting ingredients was easy, as the dining halls have scales to measure out ingredients in weight, not cups. I assumed that “the weight of 10 eggs” was referring to the amount of sugar, and five was referring to the amount of flour (Biddle). I approximated this to 1.5 pounds sugar and .75 pounds flour.

The making of the cake was challenging due to the inexact ingredient measurements listed and the capabilities of the Jordan House kitchen. The stiff peak egg whites deflated due to the amount of time zesting the lemons took, resulting in a denser cake than intended. No zesters were available to “grate the rind of two lemons” so I used the sharpest tools I could find: a potato peeler and pumpkin carving knife. The only pans available were two quarter sheet pans, so the cake was spread thinner than I presume was intended; so it baked in less time than instructed—about 25 minutes—resulting in a sponge drier than intended (Biddle).

The resulting cake was surprisingly enjoyable, despite the challenges. The sponge was not very sweet, but balanced out with the sugary icing. Each bite had a nice hint of lemon, without the flavor overpowering. Slightly more dense than a sponge should be, it would have made an enjoyable pound cake. I was surprised by how light it actually was without any leavening agents. While not necessarily what I—nor Mrs. Biddle, I’m sure—intended, it was a respectable dessert that was a refreshing break from the ultra-sweet desserts of the present.

I think the cake, while simple, exemplifies the Biddle family and their cookbook. It is rich and fulfilling, yet sophisticated in a minimalist way; exactly what they were trying to portray with their food: a humble and refined expression of their immense wealth and cultural influence within the city of Philadelphia.

In a way, this recipe book is very similar to modern “coffee table cookbooks” and the Martha Stewart era of cooking. The Biddles used food to show their wealth; modern food culture uses food to show wealth, leisure time and perfection. The feigned humility of the Biddles has transformed into the modern “I woke up like this” approach to cooking. Modern Americans do not show the time and effort that went into planning every small detail, but pretend as if they create Instagram worthy feasts every day with the ample spare time and amazing culinary skills they have. Leisure time is the new wealth. Having spare time is enviable and posting what one does with their leisure time has become the new form of social currency: afternoon tea and dinner parties have given way to social media.

The video below chronicles one of my attempts to make “A Fine Sponge cake.” When recreating and filming the recipe, I too followed modern food culture trends—slowing down the process to make sure I got the right shot and doing everything in my power to assure a beautiful product. While it is not a true record of either the modern or original process of baking such a difficult dessert, it truthfully shows the careful consideration to detail required of both the recipe and current culinary content.

Bibliography

- Biddle, Mrs. George W. Collection of recipes. Special Collections Cookbooks and Recipe Books, Smith College Archives, Northampton, MRBC MS 433.

- Dodge, Russ. “George Washington Biddle.” Find A Grave, www.findagrave.com/memorial/45621930/george-washington-biddle. Accessed 18 May 2019.

- Schweitzer, Teagan. “The Turtles of Philadelphia’s Culinary Past.” Penn Muesum, 2009, www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/the-turtles-of-philadelphias-culinary-past/. Accessed 18 May 2019.

- Sorabella, Jean. “The Grand Tour.” The Met, Oct. 2003, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grtr/hd_grtr.htm. Accessed 18 May 2019.

- United States Congressional serial set. 1186: The Range of Prices of Staple Articles in the New York Market at the Beginning of Each Month, in Each Year, from 1825 to 1863. Hathi Trust, babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3984907;view=1up;seq=608. Accessed 18 May 2019.

- Whitehead, Nadia. “High Tea, Afternoon Tea, Elevenses: English Tea Times For Dummies.” The Salt: What’s on Your Plate, NPR, www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/06/30/418660351/high-tea-afternoon-tea-elevenses-english-tea-times-for-dummies.

Recent Comments