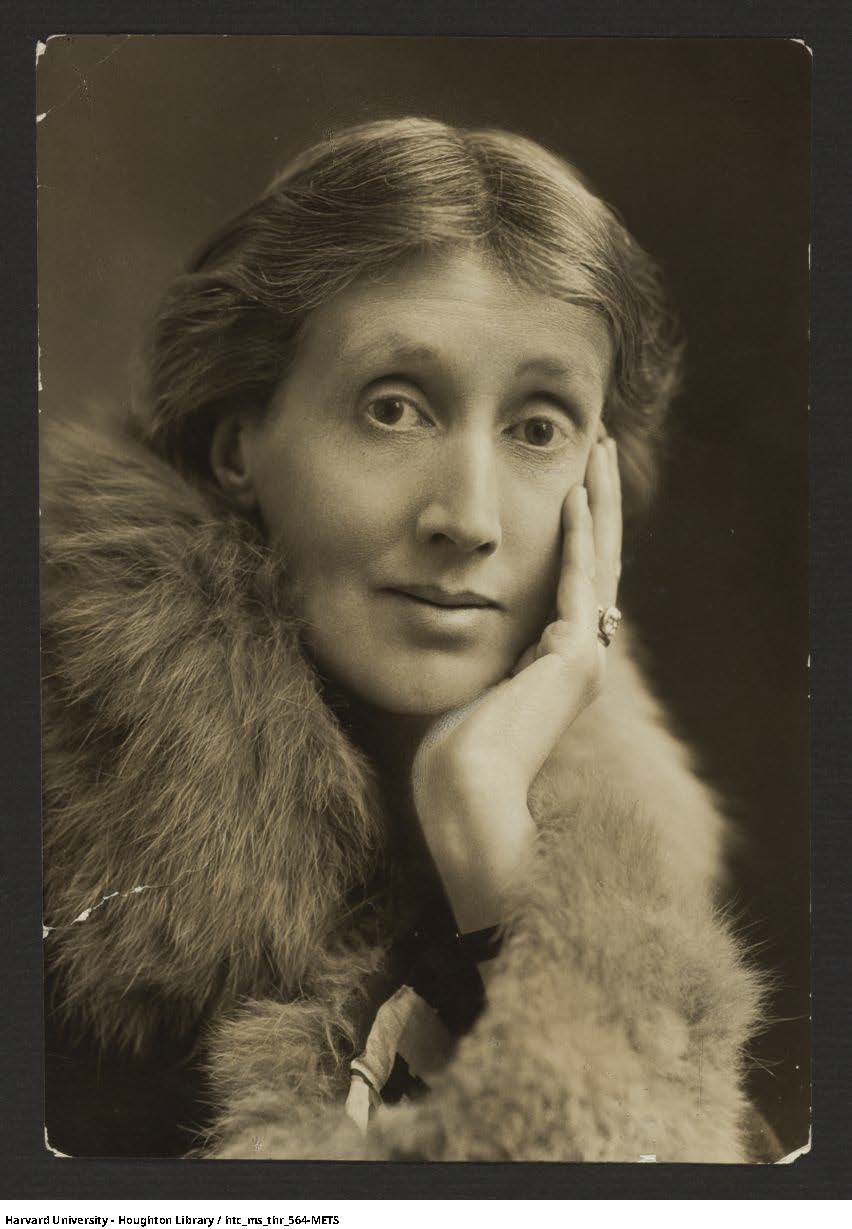

Referencing Virginia Woolf’s work Mrs. Dalloway, Boulanger eloquently carries the reader through a current critique of societal takes on feminine consumerism. Since Woolf’s times, she argues, the reductionist, frivolous views of stereotypically feminine shopping habits actually map quite clearly onto both the feminist pursuits of belonging, agency, and emotional freedom as well as onto the feminist struggles of inequality, societal isolation, and not being taken seriously. Drawing the reader in immediately with a tongue-in-cheek witticism, Boulanger says that “women be shopping–” but this isn’t shallow or surface-level, and requires to be viewed as a legitimate social force. –Abby Botta ’24, editorial assistant

Girls Just Wanna Have Fun! Reimagining Feminine Desire and Consumption in Mrs. Dalloway

Amaya Boulanger ’26

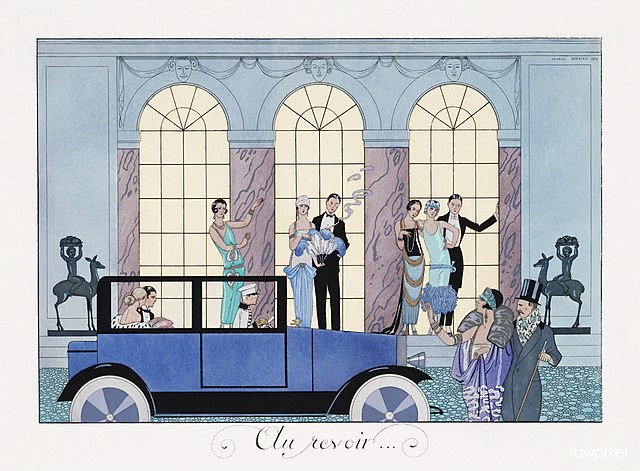

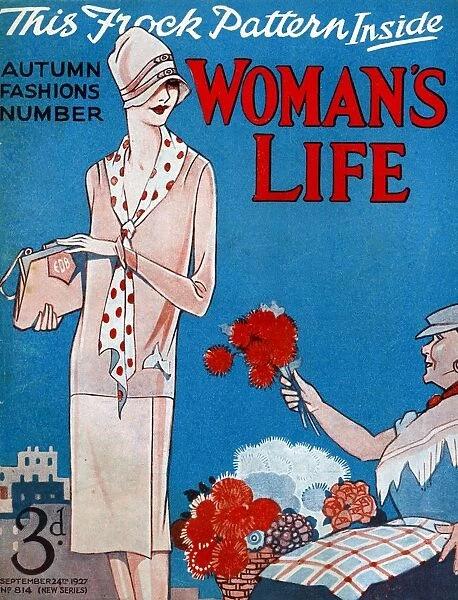

I can’t count the times I’ve stood at a register, about to drop 50 bucks on some relatively useless item of clothing, and said to my (also female) friend, “women be shopping, am I right?” This catchphrase has worked its way into my vocabulary, readily providing comic relief as I attempt to balance my guilt over participating in acts of needless consumption with the joy of self-expression I find in purchasing a unique top. Though I’m fully aware that women are targeted to further drive a corrupt consumer society, I can’t help it. I love shopping. Among my models for questioning this cycle, though, is the ultimate woman who “be shopping”: Virginia Woolf’s Clarissa Dalloway. As a post-war, post-pandemic, and mid-societal-identity-crisis novel, Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway provides an opportunity to revisit how past literary feminists have approached the woman-as-consumer in a changing world (though we must not discount the differences between early twentieth-century and contemporary feminism). In Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf explores both the advantages and pitfalls of women’s material desire, and in so doing highlights and resists a misogynistic evaluation of consumer culture.

By contrasting male and female representations of the consumer, Woolf considers a tension between anti-consumer and feminist approaches to societal improvement. Woolf wrote that her goal in writing Mrs. Dalloway was to “criticise the social system, and to show it at work, at its most intense” (A Writer’s Diary 57), which she does by constructing characters whose actions are exaggerated to define the larger concept she wants to bring into play. Both industrialization and feminism were on the rise in the time and social system Woolf was targeting, and in “showing it at its most intense,” she examines a potential mutual exclusivity of the movements. While most of her actions are relatively muted, Clarissa comes to life in her acts of consumption; she is almost a caricature of consumerism. Her very first act in the novel–“[buying] the flowers herself” –is one of consumption, foregrounding consumption as a larger element of her life (Mrs. Dalloway 1). “She [has] a passion for gloves”–not just an interest, but a passion–while “her own daughter, Elizabeth, cared not a straw” (9). Clarissa’s obsession with material items, aside from creating dissonance between herself and her daughter, draws attention to the broader societal pattern of women defining themselves through their material consumption.

The men in Mrs. Dalloway don’t escape criticism of their consumption either, though they serve more to reflect the way we conceptualize this criticism when it’s directed at women. In a conversation about Clarissa’s sewing project, Peter Walsh thinks, “here she is mending her dress; mending her dress as usual . . . here she’s been sitting all the time I’ve been in India; mending her dress; playing about . . .” (30). His anxiety–evident through his mental stuttering–about Clarissa’s interest in the dress reflects a valid criticism; while he’s “been in India” as an active figure for the state he serves, Clarissa has been wasting her time on material. Woolf admits some truth in this criticism, in that there likely is a problem with one being as regressed into consumer culture as Clarissa, but she doesn’t end the story there. Peter reduces her actions to merely “playing about,” and in so doing subcribes to the misogynistic notion that only women are to blame for society’s problem of overconsumption. “He’s very well dressed,” Clarissa thinks, “yet he always criticizes me” (30). As a text that aims to “criticize the social system,” Mrs. Dalloway acutely points out that while there is a problem with women overconsuming, proponents of change disproportionately blame women.

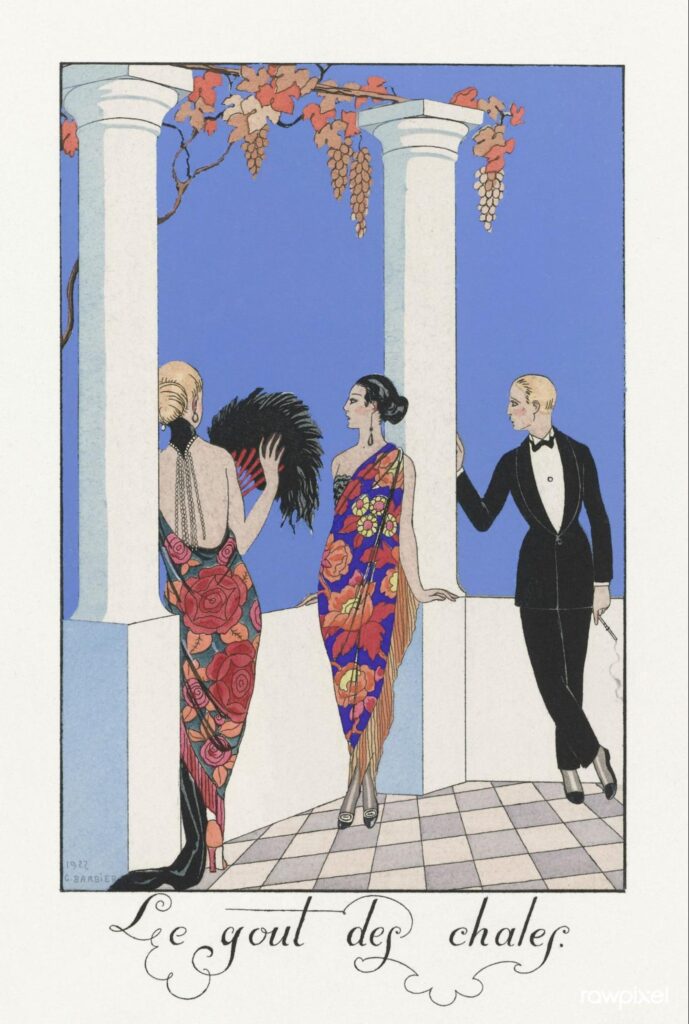

In response to the common criticisms of women as the primary consumers, Woolf explores the idea of renouncing material desire as an alternative. If women seem to be the ones perpetuating problematic cycles of consumption, should we encourage them to stop for the sake of progressive change? Of the female characters in Mrs. Dalloway, Lady Bruton is presented as the least tied to material goods and therefore the most masculine. She has “the reputation of being more interested in politics than people; of talking like a man,” and when presented with a bouquet of carnations, she holds them “rather stiffly with much the same attitude with which the General held the scroll in the picture behind her” (75). In coupling her disinterest in feminine objects with her masculinity, Woolf suggests that Lady Bruton, unlike Clarissa, resists an identity-based connection to material items. Here Woolf continues to argue that we shouldn’t be blind consumers–perhaps to be more politically engaged–however in renouncing material desire, Lady Bruton has also renounced her feminine identity. Despite doing her best to “talk like a man,” though, Lady Bruton cannot escape the fate of her fellow women. Hugh, for example, “would never lunch . . . without bringing her in his outstretched hand a bunch of carnations” (74), would never not view her as the consumer that represents modern womanhood. Her discomfort with commodities even puts her at odds with women who do subscribe to consumer culture: Lady Bruton and Clarissa, for example, do not get along (75). Despite recognizing a “feminine comradeship” between them, Lady Bruton’s lack of material desire inhibits connection with both women and men (76). In denouncing material desire, we are at risk of becoming Lady Bruton, neither equal with the men or comfortable with the women. In this dissonance, Woolf eliminates the possibility of asking women to renounce their desire, because that loses sight of feminist goals of maintaining an empowered, collective female identity. Consumption, then, presents an opportunity for reclaiming a feminine identity.

Despite her disdain, Woolf retains consumption as an essential action of Clarissa’s character to highlight the positive effects for female consumers. In an essay about Mrs. Dalloway, feminist theorist Sara Ahmed calls attention to Clarissa’s understanding of her position as not merely Clarissa, but as Mrs. Richard Dalloway. She says that Clarissa’s understanding leads to another: that perceived happiness as a wife may actually contain a “loss.” It makes one aware of the possibilities outside of her previously unquestioned life (Ahmed 333). Even though Woolf undoubtedly resists the notion of a consumed identity in a “Mrs. Richard Dalloway,” I don’t know that Woolf would agree that this “loss” consumes Clarissa’s mood, or even that that role is completely oppressive. Despite all of the freedoms that Clarissa does not have, and despite understanding that oppression, Clarissa finds happiness in throwing parties. As Ahmed puts it, she “refuses[s] to give up desire” and creates happiness for herself in the same way she finds joy in her fancy gloves: though she consumes to resist patriarchal oppression of her feminine identity, it does work. Woolf then celebrates materialism by writing in the party for Clarissa. Clarissa conceptualizes a party as a material good, as “an offering for the sake of offering, perhaps.” It is “her gift” (87). Like her gloves and her flowers, Clarissa finds pride in displaying her consumption, not to show off her wealth, but to show that she finds it fun. Her party also coincides with her effective “awakening,” further emphasizing the positive power of frivolity. Clarissa then assumes a role described by critics Nikki Lisa Cole and Alison Dahl Crossley as “consumer-in-chief”–a leader in her household above even her husband, granted by an expertise unique to women–where the happiness her consumption brings her reaches beyond surface level joy and touches on identity (Cole).

As Clarissa discovers the empowerment she experiences as “consumer-in-chief,” Woolf proposes that material consumption is a legitimate opportunity for women to find agency and freedom of expression when that freedom is systematically suppressed. Throughout the novel, Clarissa is trapped: she feels reduced to “Mrs. Richard Dalloway” and her “body, with all its capacities, [seems] nothing–nothing at all” (9). Yet in the moments that she comes to life through her consumption, she suddenly has choice: she decides exactly which flowers “she would buy herself,” and the way she presents the “gift” of her party is entirely up to her. Her consumption is a setting through which she declares an individual identity separate from her husband, and she even claims leadership in her household as “consumer-in-chief,” since she has little societal leadership. Though small, these actions allow Clarissa to hang on to a “curiosity for happiness” by which Woolf imagines Clarissa reaching a broader definition of freedom (Ahmed 333). About her later novel A Room of One’s Own, Woolf wrote that “intellectual freedom depends on material things” (Woolf, qtd. in Stevenson 114). According to Woolf, material desire is perfectly logical when it manifests a contained desire for expression and even creates the potential for future happinesses and future freedoms. Clarissa’s character attempts to redefine this kind of desire, in that it accepts it and begins to lift the pressure that women carry to be perfect consumers. Just as we cannot quell our anxieties about larger consumer culture by blaming women, Woolf argues that we need to acknowledge the good that desire does for women, past and present, fictional and real. Through reclaiming the act of consumption as a method of expression, women can hopefully, finally, begin to reach an even ground with men.

As Virginia Woolf wrote to criticize the social system, she constructed female characters through which she argued for big changes in how society perceives women. Mrs. Dalloway asserts that men have the tendency to blame societal problems of consumption on just women, shows that that desire for material objects is essential to some conception of feminine identity, and argues that women can find both happiness and agency through consumption. Though Woolf’s conclusion may have been both radical and liberating at the time, I don’t know that it’s enough. More than 100 years later, women still seem to be inclined to consume more than men, but it feels like we’ve hardly gotten anywhere in terms of equality. Trying to tackle a consumer society and a patriarchy in one go is undoubtedly difficult, and Woolf seems to have given it her best shot for the circumstances of her time, but the very cycles of consumption that women follow continue to enforce both patriarchy and oppression. Still, Clarissa Dalloway provides a valuable reflection of many women of our generation, and might help us think not just that “women be shopping” but about why “women be shopping.”

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara, et al. “From Feminist Killjoys (2010).” Mrs. Dalloway, edited by Anne E. Fernald, W.W. Norton and Company, 2021, 333–338.

Cole, Nicki Lisa, and Alison Dahl Crossley. “On Feminism in the Age of Consumption.” Consumers, Commodities, and Consumption: A Newsletter of the Consumer Studies Research Network, vol. 11, no. 1, Dec. 2009.

Stevenson, Christina. “‘Here Was One Room, There Another’: the Room, Authorship, and Feminine Desire in A Room of One’s Own and Mrs. Dalloway.” Pacific Coast Philology, vol. 49, no. 1, 2014, pp. 112–32.

Woolf, Virginia. A Writer’s Diary: Being Extracts from the Diary of Virginia Woolf, edited by Leonard Woolf, The Hogarth Press, 1972.

Woolf, Virginia. Mrs. Dalloway, edited by Anne E. Fernald, W.W. Norton and Company, 2021.

Recent Comments