We are what we pay attention to. Sadly, most of the time we are not attending to the world or ourselves. Psychologists estimate we have sixty thousand to seventy thousand thoughts a day, 99 percent of which are more or less what we thought yesterday.

– Mary Piper, Ph.D., Seeking Peace: Chronicles of the Worst Buddhist in the World

I slept and dreamt that life was joy

I awoke and saw that life was service.

I acted and behold, service was joy.

– Rabindranath Tadore

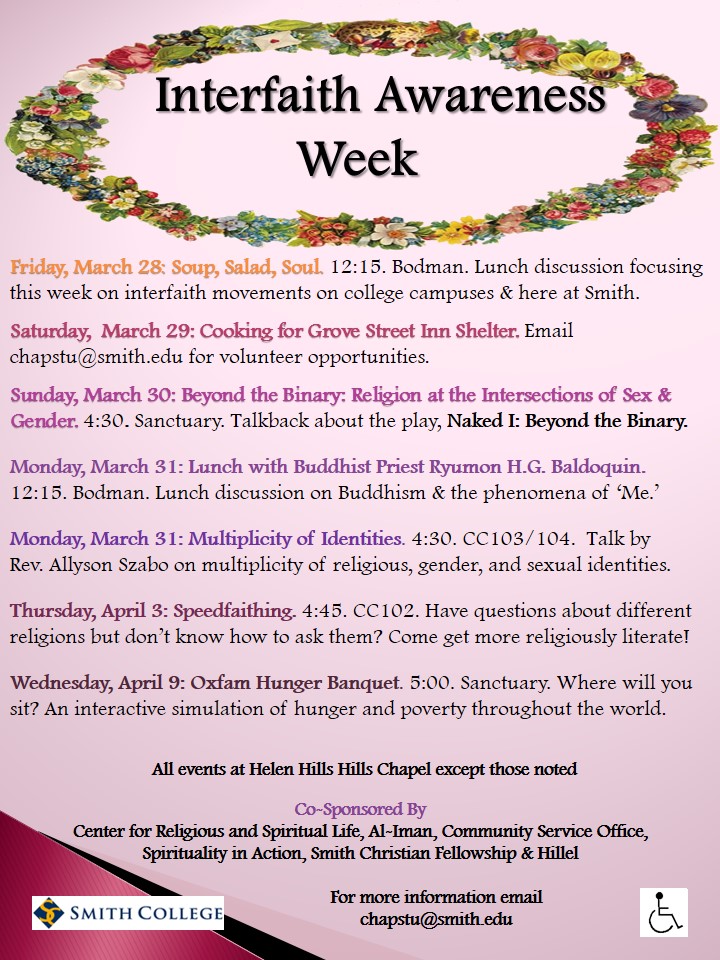

We are in the midst of Interfaith Awareness Week at Smith College, sponsored by the Student Group, Spirituality in Action.

“Awareness” programs at Smith and beyond are usually designed to bring an issue or social identity to the fore that has been underrepresented in the mainstream. Last week we had the rich and exciting Islamic awareness week put on by Al-Iman. They offered many exciting and informative events, including an amazing program about Halal food. I was able to sample some traditional Middle Eastern Sweets, including Baklava. It seems to me that “awareness” raising is a component and the responsibility of being part of a vibrant, global, prestigious diverse liberal arts community.

Spirituality in Action sponsored the Rev. Ally Szabos to come and speak at the Campus Center on Monday. As she explained, interfaith is “a movement not a thing.” It is religious pluralism, but it isn’t only religious pluralism, it is connection.

I love the definition of pluralism that Diana Eck gives in her work on the pluralism project. Pluralism means fruitful engagement and interaction between various faith groups. It implies a basic grounding in foundational truths of each religious orientation. Interfaith, in contrast, implies, to varying degrees, some areas of agreement, overlap, and even at times synchronicity. This is further complicated by the fact that in academic circles the term “pluralism” can apply to a religious adherent who may not believe all religious traditions are equal and lead to the same place, but draw spiritual substance from more than one tradition. (This definition is somewhat contradictory to how pluralism is defined in the common lexicon, but since I consider myself a religious pluralist I will try to write about this in an upcoming post!)

By eating the Baklava made by Al Iman I could, in a very visceral way, experience something that is part of the tradition of some Muslim students. Nothing can compare to engaging the senses to achieve the end of understanding—especially here at Smith where so much of what we do is cerebral.

So, how can we represent something as diverse and inherently vast as “interfaith?” What would we serve?

One way to do this would be to have a “world religions awareness week,” and try to get every religious group on campus to present their perspective and experience on their religious tradition, as Al Iman did. We could smell incense from a Hindu Puja. We could taste more Halal food, sample Hamantashen, and learn the traditions around them. We could hear Buddhist chants and learn about the concept of sacred sound.

But, at the same time, religions are not monoliths; far from it.

Scholars of world religions here and everywhere will always emphasize that there are Judaisms, Islams, Christianities, and so on. Many of us who are affiliated with a religion are quick; for obvious reasons; to qualify our membership lest we be misunderstood and associated with another sect from whom we consider ourselves diametrically opposed.

So maybe that is why instead of having a “world religions week”, Spirituality In Action is sponsoring Interfaith Awareness Week, which includes a variety of interactive events looking at social identity, spiritual practices, and intra-religious dialogue, on the one hand and service projects, on the other.

The first way to raise interfaith awareness is through relationships.

Having a relationship with someone who associates with and/or belongs to a religion that is different from our own, (and this is not to ignore the reality that a great many of consider ourselves in a category outside religious altogether, not in a category, or half in and half out of various categories) is the greatest predictor of both understanding and appreciation. The Baklava was yummy, and gave me a very sensory experience of a certain tradition. But having the privilege of knowing some of the women who put it together and shared it offered incomparable nourishment.

That is where the interfaith comes in—it is about the “inter”—the connections between the places where the boundaries of religion are themselves permeable. It is about meeting each other and learning about our unique human experiences which are simultaneously both incomparably different and undeniably common…

We know that know one person can never speak for a whole group and we know the dangers of trying. But sometimes that leads us to not ask any questions at all, and then we don’t learn and remain behind a curtain of polite but deleterious ignorance. Not asking question is one thing, but what if we shy away from relationship with that which we don’t understand and are afraid to ask about?

Through meaningful interaction — is a second way that interfaith knowledge happens.

Interfaith awareness is best raised through service. Research shows that the most fruitful interfaith dialogue takes place when people are working together for the common good. In other words, college students performing service together for something that elicits mutual passion does more for interfaith harmony than conversation itself. Some would say service work must be performed in order for dialogue to take place…

So perhaps there is not food that can be served at interfaith awareness—there is only service that can be performed.

So maybe interfaith awareness is most about connections—and all the seemingly secular but deeply spiritual, random ways that they happen— through relationships and the meaningful interactions that occur therein. It is about serving each other and the world.