On a freezing February evening in the center of Northampton, Jewish students, many wearing yarmulkes, stood in support of Dreamers. This action epitomizes the focus of the Smith College Jewish Community, the largest Jewish organization on campus. The Jewish students at Smith have made a priority of connecting ancient practices to the world today and to issues of justice and inclusion.

This year, the SCJC’s biggest project by far was the Queer Talmud weekend in December. The Talmud is a unique compendium of literature going back in its roots 2000 years. The rabbis edited and redacted religious law, philosophy, and story into 63 tractates. The Talmud forms the backbone of Jewish practice and cultural identity. But the Talmud has always been seen as a document by those in power. Inclusion of LGBTQ people has not been associated with Talmud study—until now.

The Smith College Jewish Community brought Rabbi Benay Lappe, winner of the 2016 Covenant Award for Excellence in Jewish Education, to teach Talmud through the lens of Queer Theory. The rabbis of the Talmud lived after the destruction of the Temple and the subjugation by Rome. Those rabbis meet Lappe’s definition of queer because they experienced the deep sense of otherness and oppression that queer people have experienced. For Lappe, queerness can be a way of looking at the world. Rabbi Lappe used traditional methods of Talmud study, svara, to demonstrate how the rabbis saw the Talmud as a way to look with a Queer eye. Svara is the ancient talmudic principle of human ethical reasoning to interpret text. To demonstrate svara, Rabbi Lappe gave students a statement in the tractate Sanhedrin to study.

The Smith College Jewish Community brought Rabbi Benay Lappe, winner of the 2016 Covenant Award for Excellence in Jewish Education, to teach Talmud through the lens of Queer Theory. The rabbis of the Talmud lived after the destruction of the Temple and the subjugation by Rome. Those rabbis meet Lappe’s definition of queer because they experienced the deep sense of otherness and oppression that queer people have experienced. For Lappe, queerness can be a way of looking at the world. Rabbi Lappe used traditional methods of Talmud study, svara, to demonstrate how the rabbis saw the Talmud as a way to look with a Queer eye. Svara is the ancient talmudic principle of human ethical reasoning to interpret text. To demonstrate svara, Rabbi Lappe gave students a statement in the tractate Sanhedrin to study.

“If the entire Sanhedrin [ancient court comprised of 23 judges] agree that a defendant deserves the death penalty–then the defendant goes free.”

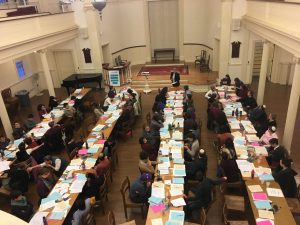

Students studied the incredible statement, then learned the rabbinic commentary accompanying it—all in a traditional methodology and in its original language. The sanctuary at Helen Hills Hills Chapel resounded with voices reciting and arguing the meaning of the text. Using svara, the rabbis concluded that it is unusual for 23 people to agree on anything. If 23 judges all agree, they are probably all biased against the defendant and therefore can’t make a just decision. The statement and its discussion is a dramatic condemnation of bias, a concept especially relevant today.

Ninety people attended the study sessions and broke bread together Friday night through Saturday evening. It was the largest program the SCJC had ever attempted. The only requirement for attendance was to know the Hebrew alphabet; the SCJC held workshops prior to the weekend to teach the alphabet to anyone who needed the tutorial. People came from the Five Colleges, all the local synagogues, and as far away as Boston and New York. They ranged in religious practice from totally secular to Orthodox. The SCJC made sure no one was excluded.

Ninety people attended the study sessions and broke bread together Friday night through Saturday evening. It was the largest program the SCJC had ever attempted. The only requirement for attendance was to know the Hebrew alphabet; the SCJC held workshops prior to the weekend to teach the alphabet to anyone who needed the tutorial. People came from the Five Colleges, all the local synagogues, and as far away as Boston and New York. They ranged in religious practice from totally secular to Orthodox. The SCJC made sure no one was excluded.

The many disparate communities joined into one single community. When the sun set on a Sabbath of study, everyone gathered to do Havdalah, the ritual that ends Sabbath time and re-enters secular time. Arm in arm, people sang together, and perhaps the world moved a tiny bit more in the direction of justice and inclusion.