“Always be on the lookout for the presence of wonder.”

–E.B. White

“That explains it!” one student exclaimed while looking under rocks on the banks of the Mill River. It was a sunny afternoon in Northampton, Massachusetts, and Jan Szymaszek’s third grade class was rapt. Autumn leaves drifted from branches, landing atop craggy boulders, or else becoming subsumed in the downward rush of water. Cameras in hand, students hopped their way through gravel and sand to capture moments that might generate questions or theories about rivers: how they move; where they lead; how they change. The launch of this year-long science unit invited students to explore their natural environment, making observations that they could then carry into classroom discussions.

But learning does not always wait for the classroom. Revelations babbled down the line of students as one young scientist, quoted above, connected Ms. Szymaszek’s questions about river volume to his noticing water under seemingly dry rocks. Could it be that the river once flowed here, he wondered? And, if so, where did it go? Why did it “shrink”?

Back in the classrooms of SCCS, students have turned to finding answers. Thinking is made visible on every wall and surface. River notes abound. Educational teammates in the pursuit of water knowledge, third grade teachers Jan Szymaszek and Amanda Newton (joined, this year, by Marcia Holden) work together to hone water curricula, adapting their projects and lessons each year.

To better understand the lessons enjoyed by this year’s third graders at the Campus School, I spoke with Jan about her iteration of the river unit. Her students’ insights, questions, and ideas reveal the ways in which tenets of Environmental Inquiry—Inquiry-based Learning; Experiential Learning; and Stewardship—permeate this learning experience for students past and present.

Inquiry-based Learning and Marker Talks

“Inquiry-based Learning is a dynamic and emergent process that builds on students’ natural curiosity about the world in which they live… [placing] students’ questions and ideas, rather than solely those of the teacher, at the centre of the learning experience” (Natural Curiosity: Building Childrens’ Understanding of the World through Environmental Inquiry, Lorraine Chiarotto, p. 7)

After working with students and student teachers for over thirty years at the Campus School, Jan—who holds a B.A. and M.Ed. from Smith College—describes herself as “ever-learning,” working to “understand big ideas and enact them in the classroom.”

“I’m intrigued with what happens when big ideas get in front of children—how they interact with ideas and become people who know how to think and learn,” she shared with enthusiasm.

“That’s what I love about teaching.”

It is with attention to “how [students] think and learn” that Jan constructs her river lessons. Perhaps the most pervasive theoretical framework at play in Jan’s classroom is Inquiry-based Learning: “It’s really [students’] ideas that guide our work together,” she shared while seated at a table filled with student work. “Problematizing” the idea of water for her class, Jan works with students to generate questions such as “How does water move through nature?” and “Where does all of the water go?”

After walking to the Mill River on that sunny autumn day, Jan introduced the practice of Marker Talks with her students, an activity used in many SCCS classrooms. The first ground rule for participating in a Marker Talk is silence. One guiding question is written at the center of a big piece of paper, and students are asked to write an idea; an answer; a question drawn in connection to that at the center. Then, they build on other’s ideas, qualifying their statements by using diction like: “I agree BECAUSE…” or “I don’t think so, BECAUSE…” or “What if we thought about it a different way?”

“Marker talks offer an opportunity for quieter students to participate,” Jan shared. “I read Susan Cain’s Quiet, which made me think differently about how I offer opportunities in my classroom for students who recharge internally.” When reading students’ Marker Talks, it seems most resonant to refer back to Chiarotto’s text, which cites one Knowledge Building principle (of twelve) as “idea improvement.” Al Rudnitsky, professor of Education & Child Study at Smith College, uses marker talks in his college classrooms and often brainstorms with Jan about Knowledge Building.

“The end-point or final product is not known at the outset” (Chiarotto, p. 8) within an Inquiry-based Learning classroom, or within a Marker Talk. So it is that Jan joins her class in collective, collegial discovery, looking to her students to lead the way while working to improve scientific thinking together.

Experiential Learning

“As Dewey (1938) and Kolb (1984) suggest, concrete experience alone does not amount to Experiential Learning. To transform experience into new knowledge, students need to derive meaning from that experience… Conscious engagement with direct experience is precisely where Experiential Learning and Inquiry-based Learning converge” (Chiarotto, p.35).

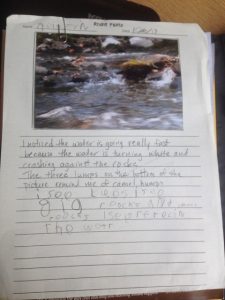

After students plodded through pine needles and mud puddles, snapping pictures and asking questions along the way, their return to the classroom was focused. In Jan’s classroom, students were asked to observe their photographs, write about what they noticed, and turn those observations into questions or hypotheses for further investigation.

“I see the watter gowing over a roke and terning into fome,” one young writer shared. “And it looks like it’s gowing faste. Why is it gowing faster on the other side?… Why dose the watter get fomy wen it crashes into sompthing? Why is that a kerent [current]? Wen thar is a roke the water splits in half and flos in difrent aryas [areas].”

To prepare for their lessons, third grade teachers embark on experiential learning adventures of their own. In collaboration with Water Inquiry, a research group led by Carol Berner, professor of Education and Child Study at Smith College, Jan visited the MacLeish Field Station, local reservoirs, and a water treatment plant alongside teachers from Jackson Street and Leeds Elementary School. Workshops and outdoor investigations allowed her to better understand the “storm to faucet” journey of water—relating the movement of water through pipes to the third grade curricular focus on the movement of water through nature.

Constructing opportunities for experiential immersion and reflective understanding, third graders’ science lessons inspire a ripple effect: In September, a group of Campus School parents organized a team of participants for the 2017 “Source to Sea Cleanup,” hosted in four states by the Connecticut River Conservancy, working in a spirit reminiscent of place-based education expert David Sobel’s words: “Wet sneakers and muddy clothes are prerequisites for understanding.”

Stewardship

“In an environmental context, stewardship refers to human actions that contribute to a sustainable future for humans, animals, and plant species alike. Acts of stewardship grow from a deep respect for, and desire to protect, the balance of nature within the Earth’s biosphere” (Chiarotto, 54).

The real rush of rivers greets students when they return to the Mill River in springtime. Third graders rear trout eggs throughout the spring semester, learning to study and nurture the fish throughout their development. Of this capstone experience, Jan shared: “Students form an intimate relationship with their trout. We don’t name them or anything like that, but the kids form a tender connection to the environment… [they become] stewards of the environment” while raising their fish before carrying them to the Mill River, where they release each trout in a collective act of giving.

Riverfest, the culminating day of this science unit, is usually the time when students embark on their bittersweet release. The day is cyclical, connecting students to their third grade origins—their first group adventure into forests and streams. Upon their return, the river has changed, and so have they. Educational researcher Kieran Egan writes of “Learning in Depth”—the notion that students who learn about a single subject in as much depth as possible, during the entirety of their elementary school careers, will better develop cognitive strategies and confidence in learning environments. Adding another dimension to the subject, third grade educators at SCCS tap into the power of expertise. Students learn from local experts—community members, parents, Smith College science professors Andrew Guswa, a hydrologist in the Picker Engineering Program, and Bob Newton, a geoscientist, with whom they confer and advance “content knowledge.”

But students leave the third grade as experts, too, carrying with them the power of nurturance and the probing of good, effectual inquiry. 2008 alumna Persis Ticknor-Swanson, now an Environmental Science major at Barnard College with research experience in Marine Biology, treasures her memories of the third grade river unit:

“My one distinct memory about… the river unit was when we released little boats we had constructed off the bridge at Smith College. We were all so excited to see what would happen to our boats, and there was a lot of jockeying among us to peer over the red railing towards the river below. I remember watching Maddy Stern’s little half lemon boat successfully bob away, while my bark-with-a-stick-in-it boat became immediately indistinguishable from everything else in the river. The highlight of the day was when Ezekiel Baskin’s massive half-watermelon boat, which was so carefully and beautifully decorated, hit the water and immediately sank, providing endless laughter to silly eight year old kids. Ms. Szymaszek did such a good job instilling in us a wonder for the natural world, and I feel so lucky to have had the opportunity to visit the river museum in Turner’s Falls and the salmon ladder. She made learning so much fun.”

Past student teacher at the Campus School, Emily Cryan (SC ’17), now a first grade teacher at a KIPP elementary school, was also inspired by her observations of third graders’ river studies. “What makes this unit so student focused,” she shared, “is that much of the lifting is done by the students… the students are the ones doing investigations, not so much the teachers. The launch of the unit sparks students’ innate curiosity and gets them to ask the question, ‘How does this work?’”

To return to the sentiments of E.B. White, third graders leave their Campus School classrooms and forever see, within water and thought, a natural, ever-present “wonder.”

Works Cited

(in order of appearance)

Chiarotto, Lorraine. Natural Curiosity: Building Childrens’ Understanding of the World through Environmental Inquiry. University of Toronto, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, 2011.

“Quote 580.” Sticks, Rocks, and Dirt, www.sticksrocksdirt.com/node/580/backlinks.