“Paradise Pond wouldn’t be so paradisey if all of the trash went into it!” an eager third grader exclaimed on a warm October morning. Circled on the carpet in Jan Szymaszek’s classroom, Smith College senior and Campus School student teacher Ruth Neils led her students through a pilot lesson of Inquiry, Inc. and the Case of the Missing Ducklings, an interactive storybook and unit designed by a group of student researchers at Smith. “The Water Inquiry project of Smith College works to improve children’s understandings of water while advancing idea-centered learning,” the program’s website reads:

“Participants investigate water as a topic that stimulates curiosity and provokes problems of understanding, as well as a medium for inquiry with which to explore the development of ideas and theories. The creation and revision of classroom resources—interactive stories, learning adventures, and tools for inspiring inquiry—allows Smith student researchers to learn alongside elementary students and educators in a dynamic, collaborative design process. Members of Water Inquiry explore best practices for sustaining scientific inquiry in schoolyards, classrooms, and communities, drawing children’s attention and imagination to water and thought– two essential, yet ‘hidden’ resources.”

Ruth began her work with the Water Inquiry project four years ago, when she entered Smith as a STRIDE student. The STRIDE program (Student Researchers In Departments) offers incoming first-year students a scholarship that includes a paid research position with a Smith professor, in this case Carol Berner, professor of Education and Child Study at Smith, who facilitates the Water Inquiry group.

Now in her senior year studying environmental science and education, Ruth joined Ms. Szymaszek’s classroom for the start of her student teaching practicum, bringing with her the first in a series of Inquiry, Inc. stories centered around the questions “Where does water come from?” and “Where does water go?” In the storybook, a cast of characters known as Inquiry, Inc. discovers baby ducklings that have fallen down a storm drain. Together with the help of readers, they must save the day, answering scientific questions and practicing design-thinking skills along the way.

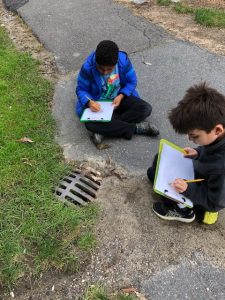

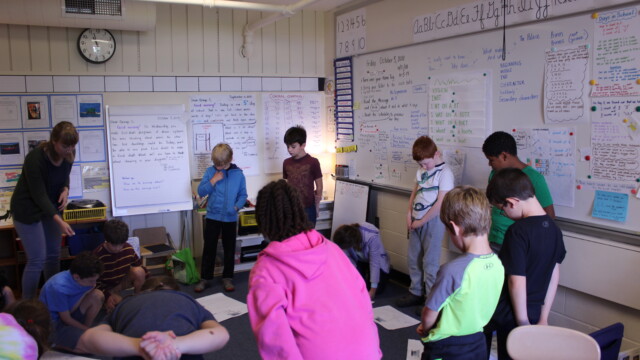

Ruth introduced students to the unit’s guiding questions through an interactive investigation of storm drains on the Campus School playground. Peering underground, students huddled over clipboards, jotting notes about their observations and questions.

Back in their Campus School classroom during snack time, Ruth read aloud from the book, stopping at a “hand-off” embedded in the text. Hand-offs were designed by Water Inquiry researchers to encourage students and teachers to “stop and think”; “stop and talk”; or “stop and make” models, diagrams, and maps in alignment with NGSS Science & Engineering Standards throughout the reading process. In this way, researchers and teachers utilize narrative structure to guide and challenge students’ interdisciplinary thinking.

“Where do you think the ducklings went?” Ruth asked during one provocation, her students eagerly raising their hands while rustling chip bags and cardboard boxes of raisins.

“The two ducks might’ve went down the pipe,” one student shared. “I’ve seen this kind of drain before,” her table-mate noted. “Some are just a grate with water underneath, and the water stretches really far. Maybe they went to the river.”

“Maybe they’re bobbing around like at an amusement park!” one student interjected with a giggle. “You know those pipes that connected [the drains]? They could’ve gone down there and into another drain!”

Ideas about connectivity spurred a chorus of agreement from classmates, and served as a segue into thinking about the rain-to-river journey of water. Students’ ideas about where water goes after it enters a storm drain (“sewer,” “eventually the ocean,” “Paradise Pond”), coupled with their observations of storm drain contents on their playground (candy wrappers, pennies), inspired discussions about water stewardship and pollution. “Water pollution is made by sewer water or drain water flowing through the pipes to a water source that then releases it into the ocean,” shared one concerned student. “That’s why you don’t want to leave paper and things on the sidewalk, because it can be washed into drains and all go to a water source, then to the ocean.”

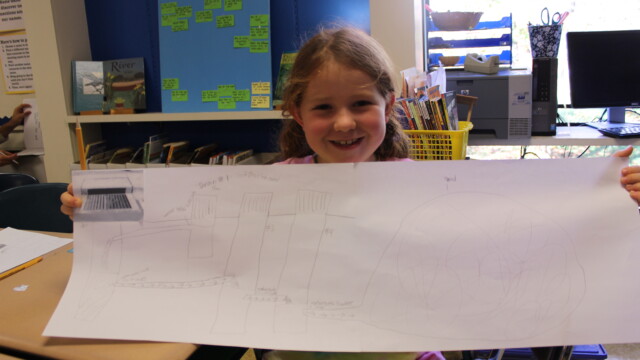

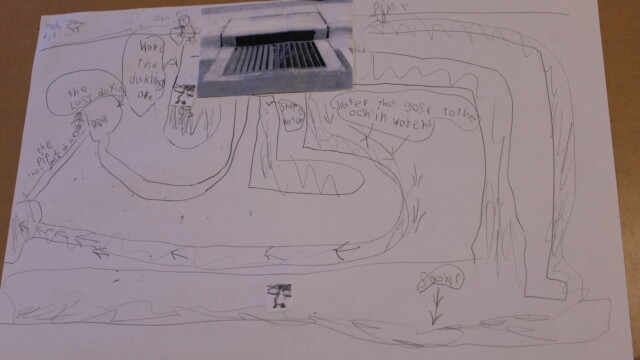

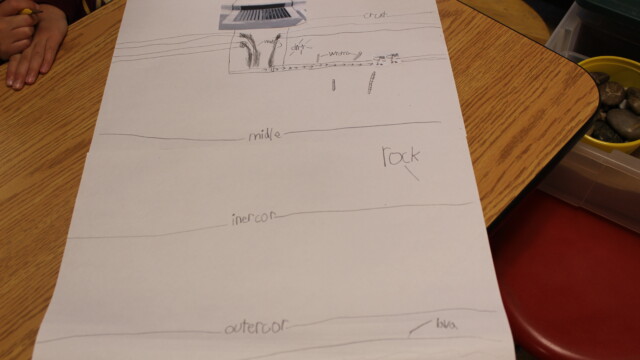

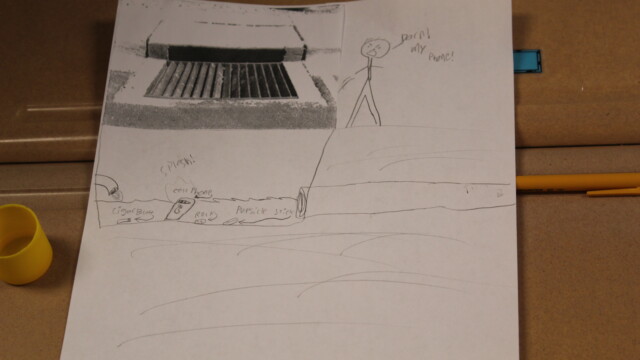

“But some gets cleaned before it goes to a water source,” another student added, allowing Ruth to shift her class’ focus to the activity of the day: drawing diagrams to represent their ideas about what happens beneath storm drains, underground.

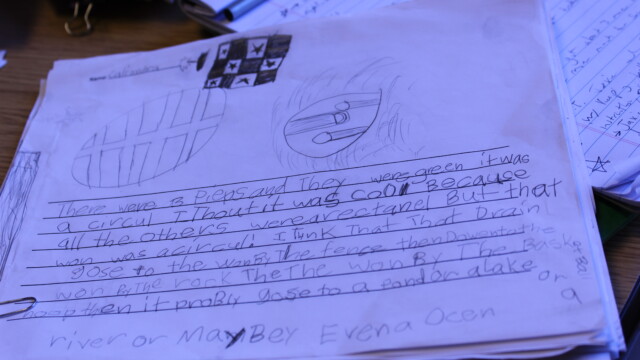

Jan and Ruth emphasized the idea of revision during this exercise– a concept that students were also grappling with in math class– by speaking to students about the drafting process, allowing them the opportunity to sketch initial ideas and hone them, on larger paper, one lesson later. This practice imbued students’ learning experiences with emphases on idea improvement, making their thinking visible to themselves as well as peers and teachers. Students shared their final products in a “Gallery Walk,” pictured below:

After students pored over each other’s drawings, Ruth invited them to share with the group one similarity and one difference that they noticed during their observations. “They all show evidence that [the drains] go to a bigger body of water,” one student said. “All of the drains go to other drains.”

A student with a pensive look on her face raised her hand, asking: “A lot of people drew straight pipes, but how does the water flow if they’re straight?”

In response to this inquiry, Ruth and Jan guided their students through the idea-building process, reminding them that “disagreement is great!,” and a helpful tool when trying to solve problems. Just as Inquiry, Inc. characters share half-formed thoughts in their storybook, students worked through their ideas together, generating hypotheses about a “fan solution; electric solution; and tilted pipe solution,” that would allow water to flow through underground pipes. Listening to their discourse, one gains a glimpse of their thinking, as well as its ascension from idea-building to problem-solving:

- “We were talking at our table about how rivers have a current, but so do drains. When it rains, it makes a flow. Pipes are never all straight. They’re usually tilted a little down.”

- “I disagree! Sometimes pipes don’t have another connected to them. If they did, it would be tilted, but if not… then it’s not [tilted].”

- “I saw a pipe straight as could be. The wind pushes [the water].”

- “Maybe somehow now we can make some amazing thing with electricity so it could push the water!”

- “When water goes down into the drain, it goes really fast down. Water is strong, so fast and strong would mean that it would go on…”

- “The reason it can go straight is that there might be a fan pushing the water. I’ve seen them in drains in movies.”

- “If you poured water on a table, it would fall off of the table, so it has to go somewhere.”

- “We were talking at the waterfall yesterday about the stages of the waterfall. The river flows like a pipe. How would the water get downhill if there were no current? There has to be a current. If it has a current before and after the waterfall, where does it get the current? Because the waterfall breaks the current.”

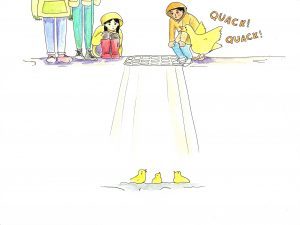

To bring her students back to the text, Ruth used students’ questions and “para-expertise,” what educational researcher Jenny Rice calls “knowledge gained through lived experience that students carry… without necessarily being able to articulate” (Williams, 52). “How can we use these ideas to think about where the ducklings might’ve gone?” she asked, showing students a brightly colored illustration from the Inquiry, Inc. storybook. In a following lesson, students were given the opportunity to put into action their ideas for improving storm drain design.

Members of Inquiry, Inc. observe ducklings that have fallen down a storm drain. Illustrations created by college students participating in the Water Inquiry project at Smith enliven Inquiry, Inc. storybooks and engage students in problem-solving processes.

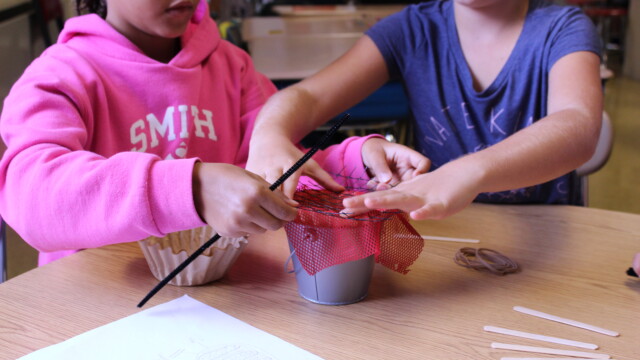

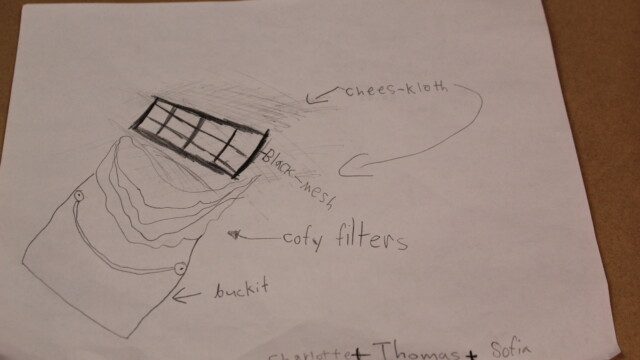

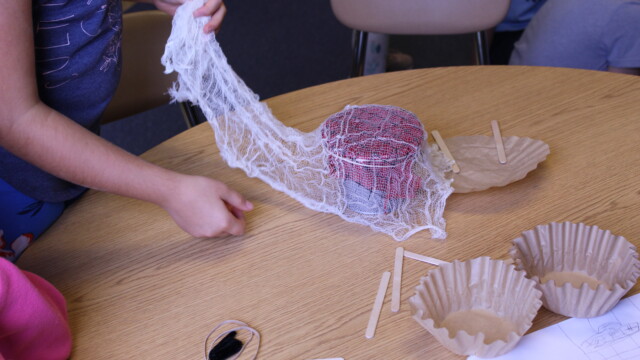

After sketching “blueprints” for storm drains better designed to “solve problems”– to keep water from flooding the streets; prevent litter from entering the water; and, most resonantly, save future ducklings from falling into their depths– students arrived in Jan and Ruth’s classroom to find a table of materials waiting for them. Small metal buckets, cheesecloth, red mesh, black wire, rubber bands, coffee filters, and Popsicle sticks were among the supplies divided into kits for each table-group.

Ruth began her lesson by introducing the word “prototype” to students. She and Jan explained this concept as “your best idea, the first time you make it… something you can learn from.” “What if your plan doesn’t work?” a student asked, to which Ruth and Jan returned to the idea of revision, a refrain woven throughout her third grade classroom. “Revision is a process that happens all of the time in engineering and design,” Jan reminded her. “That’s how real drains are made.”

“How” and “Why” questions filled the room as students set to work on their drain designs, explaining and modifying their ideas with their table-mates. Some students placed layers of coffee filters in their drain buckets, while others made “trampolines” with rubber bands and Popsicle sticks. Once they finished their prototypes, Ruth helped them test their ideas, first placing a rubber duckling on the top of their drain; then natural materials (pine needles, crunchy leaves); and, finally, “rain” poured from a pitcher of water. Students huddled over their designs, closely examining the successes and challenges of their prototypes in action.

Back on their classroom rug, Ruth guided students through a discussion about what worked in their drain designs, and what they would choose to do differently next time around. “Ours withstands environmental materials,” a student shared with pride. “We learned how to connect our materials with rubber bands instead of just balancing materials on top of each other. We weaved Popsicle sticks to [secure] them, too,” a neighboring group added.

Among their suggestions for revision, students focused on the speed (velocity) at which water traveled through their drains. “There might be such a thing as too many materials,” Ruth summarized after hearing students’ talk about how they overcompensated for the problem, blocking water out of their drains along with ducklings. “We could’ve taken out the coffee filter because the water went slowly,” one group said. “We could’ve put fewer pipe cleaners in so the water could’ve filtered faster.” Similarly reflecting on the utility of materials, other students shared: “I think the cheesecloth wasn’t useful, but it wasn’t useless. I should’ve used more tape” and, “I’d take away the cheesecloth because if we didn’t stretch it out it’d be all soggy. I think they have a good reason for making them out of metal.”

After they conversed about the “happy medium” of drain materials, students dispersed from their circle to ready themselves for recess, walking past a bulletin board entitled “Wonder Wall” and into their single-file line. On that wall were images taken by students at the Mill River on the Smith College campus during an investigation walk, one part of their annual study of rivers (for more on this, check out our coverage of the 2017-18 river unit here). In coming months, third graders will tie their Inquiry, Inc. studies to more expansive studies of rivers as ecosystems, and Ruth will bring her piloting experiences back to Water Inquiry, where student researchers will work with Professor Berner to hone their unit for implementation in other schools (yet another example of prototyping and revision).

Just as individual drains connect and carry water to rivers, so is the third grade a confluence of teaching and learning, where “student-teachers” are not just college students like Ruth, but all participants engaged in processes of building knowledge together.

To learn more about the Water Inquiry project, or to read Inquiry, Inc. stories for yourself, visit the project’s website and/or subscribe to their blog at www.sites.smith.edu/blog/waterinquiry

About Featured Educators:

Ruth Neils is a senior at Smith College majoring in Education and Environmental Science. She student-taught in Jan Syzmaszek’s 3rd grade during the fall 2018 semester. Ruth joined the Water Inquiry Project as a STRIDE student during her first year at Smith and has loved experiencing the project’s evolution.

Ruth Neils is a senior at Smith College majoring in Education and Environmental Science. She student-taught in Jan Syzmaszek’s 3rd grade during the fall 2018 semester. Ruth joined the Water Inquiry Project as a STRIDE student during her first year at Smith and has loved experiencing the project’s evolution.

Originally from Grand Rapids, Michigan, Ruth grew up surrounded by the Great Lakes, spending much of her childhood exploring the water and nature around her. Ruth says that the Water Inquiry Project perfectly combines her interests in the environment and education, fostering scientific investigation and discovery through engagement with nature.

Carol Berner earned an A.B., magna cum laude, from Harvard University, and an M.S.Ed. from Bank Street College of Education, where she joined the graduate faculty. She worked with K–12 students and teachers in New York City and Connecticut for 15 years as a classroom teacher, faculty coach and curriculum designer before coming to Smith in 2004, where she teaches courses that reflect her interests in community-based learning, education history and reform, teacher development, and imaginative approaches to teaching and learning.

Carol’s research interests include inquiry-based teaching and learning, environmental education, and arts integration. She coordinates the Water Inquiry group, a collaboration of Smith students and faculty and local K–12 teachers and is regional coordinator of River of Words, a place-based education initiative integrating watershed science, literacy, and the arts in the Connecticut River Valley.

Jan Szymaszek has been teaching at Campus School for over 35 years, delighting in every opportunity to explore ideas with the youngest learners in the Smith College community, as well as the college interns who student teach and bring new perspectives to her classroom. Over the years, Jan has participated in several research projects in mathematics education, science education and literacy education, contributing to various publications and curricula.

Jan Szymaszek has been teaching at Campus School for over 35 years, delighting in every opportunity to explore ideas with the youngest learners in the Smith College community, as well as the college interns who student teach and bring new perspectives to her classroom. Over the years, Jan has participated in several research projects in mathematics education, science education and literacy education, contributing to various publications and curricula.

The Water Inquiry Project offered a wonderful opportunity for Jan and her students to examine how ideas about water, in general, could support the existing Third Grade River Study, broadening the scope of the ideas and possibilities under investigation. Through this work, Jan is able to continue to pursue her passion and curiosity about all things related to teaching and learning.

Works Cited:

-“‘I Don’t Know What To Write’: Para-Expertise and Student Writing” by Amy D. Williams, English Journal Vol. 108 No. 1 http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/EJ/1081-sep2018/EJ1081Sep2018Dont.pdf

Written by Brittany Collins

9 thoughts on “Inquiry, Inc. Comes to Campus School: Student Teachers, Student Researchers, and STE(A)M at Smith”

Comments are closed.