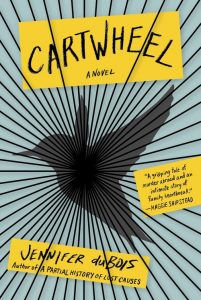

Jennifer duBois ‘96 is the author of A Partial History of Lost Causes, which won a California Book Award for Fiction, a Northern California Book Award for First Fiction, and was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Prize for Debut Fiction. The National Book Foundation named her one of its 5 Under 35 authors. Her second novel, Cartwheel, was the winner of the Housatonic Book Award for fiction and was a finalist for a New York Public Library Young Lions Award. An alumna of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and Stanford University’s Stegner Fellowship, duBois is the recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award and a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellowship. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Playboy, Lapham’s Quarterly, American Short Fiction, The Missouri Review, The Kenyon Review, Salon, Cosmopolitan, ZYZZYVA, and elsewhere. A native of western Massachusetts, duBois teaches in the MFA program at Texas State University. To learn more about her work, visit https://www.jennifer-dubois.com

Jennifer duBois ‘96 is the author of A Partial History of Lost Causes, which won a California Book Award for Fiction, a Northern California Book Award for First Fiction, and was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Prize for Debut Fiction. The National Book Foundation named her one of its 5 Under 35 authors. Her second novel, Cartwheel, was the winner of the Housatonic Book Award for fiction and was a finalist for a New York Public Library Young Lions Award. An alumna of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and Stanford University’s Stegner Fellowship, duBois is the recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award and a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellowship. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Playboy, Lapham’s Quarterly, American Short Fiction, The Missouri Review, The Kenyon Review, Salon, Cosmopolitan, ZYZZYVA, and elsewhere. A native of western Massachusetts, duBois teaches in the MFA program at Texas State University. To learn more about her work, visit https://www.jennifer-dubois.com

1) Can you briefly describe your academic/professional path after you left Campus School?

“After graduating from Campus School in 1996, I went to the Williston Northampton School, then Tufts University, where I majored in political science and philosophy. The philosophy I loved, the political science I was extremely bad at; I also took a bunch of creative writing classes and emerged (I think?) with an English minor. I spent a year teaching social studies outside Boston, applying to various far-fetched opportunities. I wound up in the bizarre situation of choosing between the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and a job as an officer with the CIA. After a lot of anguished debate, I went with Iowa, where I wrote my first novel. After graduate school I received a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford. I’ve been teaching writing ever since then, currently in the MFA program at Texas State University. My third novel, The Spectators, will be published this spring.”

2) Do you have a favorite (or funny!) memory from your time here?

“I really loved looking for horse chestnuts under the ginkgo trees. Also one time my pants fell down while I was on the balance beam and the gym teacher had to give me a rope to hold them up for the rest of the day. That’s pretty funny in retrospect.”

3) In what ways was writing a part of your life growing up? When did you know that you wanted to pursue writing in your professional life?

“I think writing was always my favorite hobby as a kid, and by the time I was a young adult I was certainly aware that writing would always have a special status in my life. But it was really my admission to Iowa that made me believe I should–and maybe even could–put writing at the center of my life.”

4) How has your approach to, or perspective of, writing changed throughout your life as an author?

“Probably the main shift has been the way that writing has moved from the margins of my life–this extra, exciting thing that I enjoyed and might be good at–to the very core of my identity. When I was writing my first novel, I felt this profound sense of privacy and anonymity–I didn’t worry about what other people would think of my book, because the idea of other people reading it at all seemed so far-fetched. I think this was a sort of adaptive denial. With my second book, I was more aware of what it might feel like to have readers, but I also understood that no one was waiting for this novel–no one would really care if I didn’t write it at all, which was freeing. Now that I’m in the realm of two-book contracts and tenure-track teaching, writing books is both expected and required of me. This is a lucky position to be in for a million reasons, but I do think imagination functions best when its exercise isn’t mandatory–if it can feel a little subversive, even better.”

5) What writing accomplishment are you most proud of?

“Finishing my third novel, The Spectators. Not because it’s better than my first two, necessarily, but because writing it was so much harder.”

6) Are there teachers, mentors, or authors who inspired your creative path?

“Yes! Sandy Warren at the Campus School (more on her later!), Lisa Levchuk and Peter Gunn at Williston, Michael Downing and Alan Leibowitz at Tufts University, and Ethan Canin at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop come especially to mind.”

7) Do you have any current or future projects that you might be willing to share with our readers? What’s next for you?

“I’m working on a new novel tentatively titled The Last Language. After writing three really structurally complex books, I promised myself a short novel with a single first-person narrator which unfolds linearly in one timeline. Writing this one has been like a vacation.”

8) Can you tell us a little bit about your approach to teaching writing? Has teaching changed your own creative process?

“I base a lot of my graduate teaching around the concept of literary values–those underlying preferences/pet peeves that shape how we respond to the fiction we read, and what we aspire to do in the fiction we write. I tell my MFA students they have two main tasks: to identify and articulate their own values, and to learn how to engage critically and usefully with work that doesn’t share them. That’s where the language of craft comes in. I learn a lot from my students and value my teaching tremendously–although like any full-time job, its effect on my creative process is probably not that great.”

9) Do you have any book (or poem, or short story) recommendations for our Lab School audience?

“A few favorites from the last couple of years: Euphoria by Lily King, Private Citizens by Tony Tulathimutte, and Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders, which I love with a deep, impious reverence.”

10) What would you tell Campus School students who hope to pursue writing, as a vocation or avocation, in their future? What do you feel were your keys to success?

“If success is publishing books, then the key for me was all the time that I’ve been given. Through the support of Iowa, then Stanford, then an advance that allowed me to work part-time for a while, I went five years without a full-time job. This was an immense privilege, and it’s absolutely how I managed to write two novels so quickly. I say this not because you can’t write books around the margins of other major commitments (you absolutely can!), but because insufficient time is probably the most critical barrier to creating art–so I think it’s really important that writers acknowledge how they bought their time, and exactly how they paid for it. Now that I teach full-time, writing is much harder, and much slower. But it is possible, and it is immensely sustaining. If writing feels that way to you, you have to fight to make some space for it in your life. People often wonder if their writing deserves that space, or how they’ll know if it does. But if writing feels meaningful to you, the answer is always yes. The bad news is that no external validation is ever guaranteed; the good news is that writing really is its own consolation.”

11) Is there anything else that you would like to share about your time at Campus School, or beyond it?

“When I was in fourth grade, I was pretty good at spelling–a skill that’s since atrophied–and I tended not to need to study for the weekly tests. So Sandy Warren assigned me a project of writing stories using the spelling words and reading them aloud to the class each week. At the end of the year, Ms. Warren compiled my stories into a little book–I think the class did illustrations. This was my first experience of writing stories regularly, or reading them out loud, or learning that people might like them. It was my first experience responding to what I would come to understand was a technical constraint–the kind I’d encounter in my fiction writing classes in college, and eventually assign to my own undergraduates. And it was one of my most memorable experiences with the kind of teaching I’d one day aspire to–creative, demanding, individualized, and far-seeing–and which SCCS so effectively fosters. I don’t think this spelling story experience made me a writer–I think that was probably in there already–but I do know it was the first time I ever thought, hey, I might be kind of good at this. What a gift to give to a child. For this, and so much else, I’ll always be grateful to the Campus School.”

Transcribed by Brittany Collins