In September, Jewish students entered a slightly different time zone—Ancient Standard Time. Coming to school as Smith students, theirs was the season for back-to-school, classes beginning, and maybe Mountain Day. However, as Jewish students, September was also Rosh HaShanah, the New Year, followed ten days later by the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur. This was a sacred time to pray, to ask for forgiveness, and to think about change. The ten days between the two holidays are called the Days of Awe. They are called this because it is the time to mend what one has injured—in one’s family, in the world, in one’s life—and to commit to change before, as tradition tells, the Book closes.

Living simultaneously in Smith Academic Time and Ancient Standard Time can be difficult. Feelings of Awe for most modern and postmodern people are tenuous at best. In college, Awe doesn’t always compete well with the anxiety around Calculus Boot Camp or Statistical Thinking, or Comparative Politics. The 26-hour fast for Yom Kippur is uncomfortable, but it can be quite frightening to miss classes with the threat of falling behind.

So the High Holy Days ask for significant sacrifice and discomfort. It is okay to be uncomfortable. But it is also okay if Smith Academic Time has to prevail over Ancient Standard Time. Some students attended the full service and some dropped into services when they could between classes. They did their best, which is good enough. Tradition tells us that we are actually forgiven before the High Holy Days even begin, yet we are still required to do the work of Teshuvah—changing what needs to be changed—to the best of our ability.

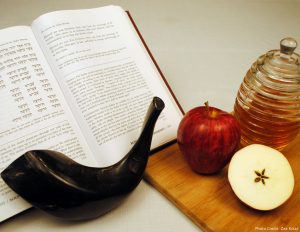

Students came together and shared a common time zone for a short while, breathing deeply and sensing what needs to be done differently this year. Seventy-five students gathered and prayed in a small circle in Helen Hills Hills Chapel. Students from each class were called up to the Torah to receive a class blessing. Three Baalei Tekiah—shofar blowers—sounded ram’s horns as everyone called out the names of the shofar cries. The last call left people speechless.

After the morning service, students gathered a picnic lunch and walked to the pond for Tashlich, the throwing out of sins. Students named what needed to be thrown out, both in the world and in themselves. They “transferred” these “sins” onto stale pieces of bread and tossed them into the pond under the distant watchful eyes of geese.

Then they returned to the world around them, back on Smith Academic Time, but with a little of the Ancient still ticking away inside.