“It makes sense to draw parallels between how we understand literacy, how children develop literacy, how we teach literacy, and how we understand and develop this other sort of sub-literacy, computer science literacy,” said technology teacher Joe Bacal, seated in the Campus School computer lab one fall morning. “The things that we do in Scratch fit into a larger framework of literacy,” he added.

Tucked beneath the music room in a windowed corner of Campus School, students in grades 2-6 engage in weekly lessons with Joe, who joined the Campus School community in September after a rich and varied career in teaching, school counseling, and educational technology, most recently as an IT specialist at Smith College—a role in which he collaborated with professors to integrate and facilitate digital technology programming in college courses across disciplines.

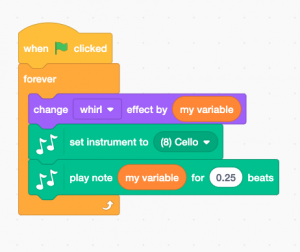

Scratch is a block-based programming tool that Joe utilized during his time as a counselor, discovering that students found it “empowering” (“They got control of something… it’s expressive,” he shared), and he is now using the platform to scaffold digital literacy and hands-on experimentation among Campus School students.

“Creative computing and computational thinking are two terms that sort of coexist and are the tip of the iceberg on this whole approach,” Joe said, reflecting on his pedagogy. “Scratch itself is a core tool. It comes out of the same sort of academic circles [as Maker Education and digital literacy education], and it’s a tradition that goes back to the 70’s and has to do with thinking of computers and technology as tools for creativity, and as things that you build stuff with as opposed to things that you [use] passively. I’m working to make sure that is apparent and at the forefront across the grades.”

Scratch was developed in 2003 by the Lifelong Kindergarten Group at MIT, facilitated by Mitch Resnick, LEGO Papert Professor of Learning Research at the MIT Media Lab—a professorship that is eponymous of Seymour Papert, a world-renowned mathematician and learning scientist who pioneered constructionist learning methods grounded in educational technology during his own tenure at the school. Joe cites Papert as having particular influence on his own work in the classroom, in combination with “a pantheon” of progressive educational technology reformists who worked alongside Papert or were born out of his philosophies.

Having attended graduate school at Bank Street College of Education, after which he taught at the Bank Street lab school for seven years (Bank Street a seminal leader in education reform, founded in New York in 1916 by Lucy Sprague Mitchell, who was inspired by the philosophies of John Dewey), Joe braids the philosophies of Constructivism (the idea that people “construct knowledge and meaning from experience” and learn by doing—a central belief at Bank Street) with Constructionism (the idea that people learn best by making and sharing products with an authentic audience—a theory spearheaded by Papert).

Scratch technology introduces students to the “story” and language of programming.

“I was at a conference a long time ago with Gary Stager,” Joe told me (Stager is a worldwide expert on computer programming and technology in education, who studied under Papert). “I said to him, it’s [strange] how the Bank Street world and this world [of Maker Education] are two separate worlds. They’re not totally disconnected, the progressivism of Bank Street… fits really well with all the Papert stuff. People learn by doing, and building, and [making] with their hands.”

Channeling these theoretical foundations and inspirations into coursework, Joe introduces students to programming through Scratch at gradated, differentiated levels across grade levels. From familiarizing students with the language of the practice, to sharing provocations for students’ use of the platform, there is great nuance behind what might, on the surface, seem like a character dancing on a screen, or an animal running around. Observing the process behind students’ products illuminates for viewers just how much consumers take for granted the digital products with which they engage on a daily basis.

Joe himself contemplates “process versus product” in his teaching, realizing that determined learners and those for whom technology comes easily may experience different rates of return from their efforts to learn the language and process of programming. “I try to be really mindful and reflective about how much I am trying to push people to be at their own zone of proximal development… giving everybody the scaffolding that they need, and not too much, and not too little, and [honoring the fact that] everybody has different strengths, trying to tap into those. Ultimately, the most motivating this is when kids feel confident and interested at the same time.”

Walking through the computer lab doors during a fifth grade Scratch session, students sit in pairs, pensively studying their character creations, clad in blue headphones. Every now and then, there’s an excited gasp, a giggle, a growing coder raising their hand for clarification from Joe, who weaves between the rows of computers, observing and expertly engaging students about their processes and products. Listening in on student discourse—the design-thinking and iterating that occurs as students seek to align their visions with the images on the screens in front of them—the idea of literacy resonates. There is a language bubbling here, and with it so many possibilities—each computer a sentence in the growing story of technology at Campus School.

Written by Brittany Collins

3 thoughts on “Programming through Play: Scratch Technology at Campus School”

Comments are closed.